Network strategies and performance across the cycle

December 2000

The big questions being asked by airline financial analysts at the moment must include: how is it possible that Air France is growing fast, with ever increasing profitability, while former industry benchmarks like KLM and BA are slipping into the red? How long will Air France sustain its profitable growth? Will the new "shrinking" strategy of KLM and BA work? In this article, Lucio Pompeo from McKinsey & Co. offers some insights on the dynamics of airline economics and on how network strategies can affect performance across an industry cycle.

There are different drivers of earnings volatility. The first and most obvious driver is when the increase in capacity exceeds the increase in demand, leading to declining load factors. This is the classic situation where "too many seats are chasing too few passengers" and tends to be an industry–wide phenomenon.

The second driver is when the difference between unit costs and unit revenue (yields) narrows. This can be triggered by rising costs for non–influenceable items such as fuel, but also by stagnating labour productivity (through concessions to labour groups), a typical upturn syndrome. Or earnings can be related to the revenue side of the equation. Certain markets and customer segments tend to be more exposed to traffic and/or yield declines than others in an overcapacity situation. This in turn will very often trigger competitive behaviour, which is responsible for a major part of earnings volatility.

To illustrate in a simplified way the competitive effects in a cycle downturn, one can look at the four different types of markets in which a major network carrier competes, each one with specific competitive structures:

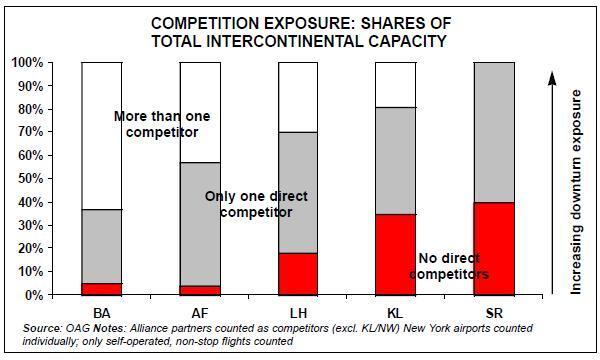

Long–haul direct: in these markets the competitive structure is very dependent on the size of the traffic flow and the regulatory environment. It is not unusual for only one or two carriers to compete for this traffic, and sometimes they cooperate under a code–share agreement (or an antitrust immunised agreement, which in effect allows two airlines to act as one). Competitive behaviour in a cycle downturn is likely to be determined by the number of competitors. As an example, BA is significantly more exposed than Swissair, as about 60% of its intercontinental capacity is in highly competitive markets with more then two competitors, while Swissair never faces more than one competitor, and 40% of its capacity is in routes without direct competitors. Of course, passengers can and do connect in hubs, so being the only player on a route does not mean having a monopoly. However, the time–sensitive passenger is likely to give this carrier a high share and also premium yields, and the downturn exposure will be lower.

Long–haul connecting: this tends to be a much more competitive market. For passengers desiring to travel from Berlin to Boston or from Marseille to Osaka, there are always at least 5–6 airline systems competing against each other, trying to attract them into their hubs, whether at Frankfurt, Paris CDG, London Heathrow, Amsterdam or Zurich. Moreover, competition is likely to involve very aggressive prices, reflecting the low marginal costs of filling empty seats.

These markets can be expected to be the ones with the highest yield declines in the event of overcapacity on the long–haul segment. Hub location, frequencies offered, and quality of connections are obvious competitive advantages which apply also in a cycle downturn. However, as the trade–off between time and price moves towards the latter in a downturn, an increasing share of passengers will opt for a detour in exchange of a favourable price, especially considering the lower relative impact on elapsed time in long–haul.

Short-haul direct: in the European environment there are typically two competitors — the two flag carriers of the two countries involved, although niche and low–cost carriers are increasingly entering these markets. In some markets, like the UK, multi–airline competition on short hauls is now the norm. The competitive behaviour of the mainline carriers in this situation will be more or less fierce, depending on the overall demand and relative market position and frequency share. Exposure in this market is likely to be determined by the same factors as for longhaul direct markets, with the exception that low cost competition may intensify during a downturn because it is at such times that passengers become more price–sensitive. Also cycle downturns may facilitate entry of new low–cost carriers because of the availability and lower cost of aircraft, crew, airport facilities, etc.

How does network strategy affect downturn exposure?

Short–haul connecting: these markets have similar characteristics to the long–haul connecting markets, with the difference that hub location and quality of connections is much more important. The consequence is that typically only 2–3 airline systems are really competing against each other for these traffic flows. So the competition will be fierce, but less than on the long–haul connecting markets. An additional factor in these markets is regional carriers, specialising in exploiting under–served markets and entering with direct services. However, this type of competitive threat is not expected to depend on the position on the industry cycle. To summarise, the more revenue an airline generates in exposed markets, the greater the drop in yield is likely to be if somewhere in the global airline network overcapacity is created.

Airlines like KLM, Sabena and Swissair, with relatively small home markets and highly dependent on connecting traffic, are quite exposed, especially as a high proportion of revenues are generated in competitors' home markets, where these airlines cannot count on the full tool–set to control revenue quality (FFP affiliation, brand awareness, contracts with travel agencies and corporations).

This means that competition is based essentially on price and on schedule competitiveness and these airlines tend to have a quite exposed traffic structure, as they have to rely on a high number of connecting passengers. To take KLM as an example, its long haul network is based on connecting Amsterdam to Northwest hubs (Minneapolis, Detroit, Boston), but point–to–point traffic on these routes is quite thin, so there is a high proportion of double connections — this exposes KLM’s long haul network to intense hub competition and partly explains its poor yield). These airlines compensate by a fairly limited exposure on the direct routes, as they typically face little direct competition.

Airlines operating from large markets, like BA, are less dependent on connecting revenues, and some like BA are attempting to reduce their exposure further by downsizing, in effect rejecting low yielding connecting traffic on some long–haul routes. This move seems to be showing some initial positive results. BA is combining capacity reduction with significant product improvements, such as beds in business class, which will certainly attract more premium traffic, but at the price of higher seat costs.

However, BA is potentially exposed to increased competition on the direct long–haul services as the result of the number of competitors in theses markets (and that number would obviously increase if BA were to find itself in a open skies regulatory regime across the Atlantic).

Again, the cycle dynamics may play a role in determining the success or failure of this strategy: if there is a strong displacement from business to economy (as in the last cycle downturn, when the load factors of European airlines dropped on average by 15 percentage points in business class and increased by five percentage points in economy class), this might create a challenge to airlines with oversized premium compartments.

What about Air France? How is it possible to increase capacity at two–digit rates and still be able to increase both load factors and yields? The explanation might lie in the different balance between offered long–haul capacity and overall long–haul traffic growth.

The need for balance

It appears that Air France still has some room to grow and will find a high share of passengers in its home market, without need to buy market share on connecting markets. Air France’s strong position on the French domestic market is likely to help protect yields in other French cities, even if increased competition from the Qualiflyer Group can be expected. Of course, Air France’s longhaul growth cannot continue indefinitely, and at the current growth rates Air France will reach the penetration levels of other hub carriers quite soon. Realising a robust network with more stable profitability requires balance. Balance is required in different areas:

Balance between exposure and growth in connecting markets. Growth in connecting markets is the easiest way to get additional traffic at virtually no additional cost. Most airlines have been well able to structure their schedules so as to dramatically increase the number of connections offered, and many hubs have experienced a proliferation of connecting waves (typically going from 3–4 waves to up to 6–8 waves). Airlines like Sabena have been able to increase dramatically their connecting traffic in the past two years. Overdoing this process could increase the exposure in case of downturn. There are, however, two ways to limit this exposure:

- Appropriate Origin/Destination selection: certain connecting flows, for example from a secondary destination to another secondary destination (e.g. Oslo–Kinshasa via Paris) are by nature less exposed than trying to attract people from a strong competing hub to a major destination (e.g. Frankfurt–New York via Paris). This can obviously only work if an airline has a quite broad long–haul destination portfolio, like KLM, and is significantly harder for airlines like, say, Sabena.

- Protection of feeder traffic through alliances: a way to secure and reduce volatility for connecting flows is to develop significant market clout in the geographic area where the tickets are sold. This can be best done through alliances with carriers that have a strong market position. Examples are Swissair and Lufthansa, which are estimated to generate a significant share of their long–haul connecting traffic from the home markets of their alliance partners, like Sabena, LOT and SAS, Austrian respectively.

Balance between hub connectivity and exposure in secondary airports. Hub economics dictate the concentration of the largest possible number of flights in one single hub. Only in this way can the number of connections offered be maximised. However, doing this exposes some important airports within the area of influence (e.g. Dusseldorf for Lufthansa, Geneva for Swissair or Manchester for BA) to attack by the competing network carriers or carriers from other continents (like Delta Airlines, which serves cities such as Nice or Stuttgart directly from the United States). The economic trade–off is between the additional cost of offering direct long–haul services from secondary airports, and the additional revenue captured (net of network cannibalisation).

The direct service between Basle and New York introduced by Swissair in 1999, and already withdrawn, shows how difficult is to create new direct services from secondary airports without enough base traffic and without an effective short–haul feeder structure.

Balance between capacity offered and home market potential. As mentioned before, the ratio between the long–haul capacity offered in the hub and the total local market potential is an indicator of the combined effect of local market position and dependency on connecting traffic. Swissair and KLM are particularly exposed, due to the small size of the traffic flows to and from Zurich and Amsterdam respectively, while Air France still has some more room for long–haul expansion. Alliances and consolidation can reduce this type of exposure, as complementarity of network strategies and exposures can significantly contribute to increased stability of earnings. From this point of view, the unsuccessful attempt to merge KLM and Alitalia would have been an effective combination of a carrier with an "oversized" net–work in a small country and a carrier with the opposite characteristics.

Balance between product configuration and achievable yields. As point–to–point premium passengers generate higher unit revenue than connecting passengers, airlines focusing on the first type of passenger can afford higher–cost product configurations, such as more space for seating, beds, etc. If the network strategy is to capture substantial connecting traffic, the seat unit costs must be lower, so that they can be covered by the lower yields generated. The question is not which of these two strategies is better, but whether network strategy and product configuration are aligned. BA is a good example of the first strategy, with its new emphasis on point–to–point premium passengers and a high–end first class and business class product offering, while KLM best represents the second strategy, with a very high share of connecting traffic and corresponding high density seating configuration and two–class product. Problems would arise if an airline pursued a KLM network strategy with a BA product strategy. Traffic mix is also a key driver of yields, both for point–to–point and connecting passengers. As traffic mix tends to deteriorate significantly in a downturn, some flexibility to re–adjust product configurations would be required to re–align unit costs to the achievable yields. Or, if the yield curve allows it, capacity could be reduced to "cut off" the lowest yield segments, like in the case of BA’s long–haul network, with the replacement of 747s by 777s. This obviously helps only if the improved yields and load factors outweigh the unit cost increase.