Continental: high growth at low risk?

December 1999

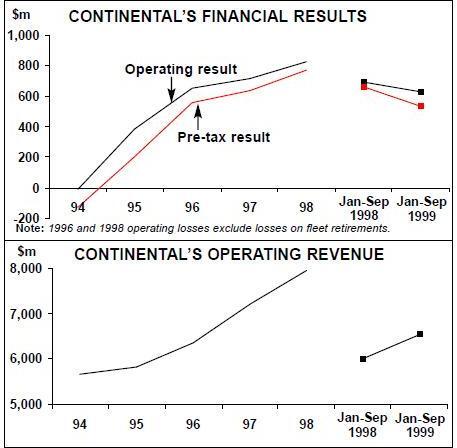

Continental is probably the biggest 1990s success story among the major US carriers. After emerging from its second Chapter 11 visit in April 1993, the company staged an impressive financial turnaround four years ago. Since then it has consistently achieved high profit margins, despite rapid international growth and a process of bringing wages to industry standards.

Much of this has been the result of a turnaround strategy put in place by a new leadership team, headed by Gordon Bethune, the current chairman and CEO, five years ago. While Bethune was credited for engineering the rescue and was named as one of the 50 best CEOs in America in a recent survey, his right–hand man Greg Brenneman, president and COO, is now one of the most sought–after candidates for CEO position at the largest US corporations.

The initial phase of the strategy involved scrapping Lite (the low–cost venture launched in 1993), phasing out the 21–strong A300 fleet, eliminating 4,000 jobs, outsourcing maintenance at two locations, strengthening hub operations, bringing back first class, improving on–time performance, and renegotiating debt, aircraft deliveries and leases. All of that led to an immediate return to profitability in the second quarter of 1995.

In 1997 Continental identified another $100m potential non–labour cost savings for 1998 (through eliminating waste, doing things more efficiently, using new technology, etc). As that target was exceeded, the goal was raised, and the savings will now add up to $210m by the end of 1999.

This, together with the benefits derived from fleet renewal, higher aircraft utilisation, productivity improvements and lower distribution costs, has enabled unit costs to be kept in check despite considerable wage pressure over the past couple of years.

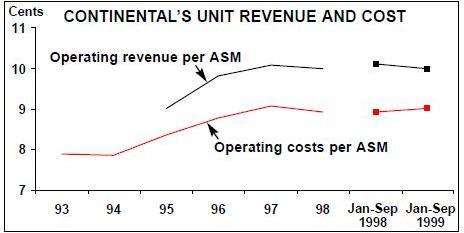

Costs per ASM were 8.93 cents in 1998. After surging in 1996 in the wake of Lite’s disappearance, Continental’s unit revenues have remained stable, at around 10 cents per ASM, in the past three years. The adverse effects of rapid expansion have been compensated for by a rise in the business traveller content of total traffic, reflecting product enhancements and high operational reliability.

The repeat awards won by Continental testify to the consistency of its product quality. In their independent annual study, J.D.Power/Frequent Flyer magazine have again named it the best major airline in customer satisfaction on long–distance flights — a distinction Continental has won in three of the past four years.

But the airline is proudest of its inclusion, at the end of 1998, as one of the “100 Best Companies to Work for in America” in Fortune magazine’s annual survey. The 10% operating profit margin target set by the 1995 turnaround plan was achieved in 1996 (when substantial fleet charges are excluded) and has been maintained (10.4% in 1998 and 9.6% in January–September 1999).

These were not the highest margins around, but Continental’s average return on equity (37% in 1998) has exceeded the industry average. These were significant achievements in a period of major expansion. After a 10% capacity decline between 1992 and 1996, Continental’s ASMs surged by 9.9% in 1997, 10.6% in 1998 and 9.4% in the first nine months of this year.

The financial community has been impressed by Continental’s ability to grow without adverse impact on the bottom line. However, the general concept of capacity addition (by anyone other than Southwest) is one that evokes fears in the minds of US airline investors, bringing back memories of damaging price wars and desperate market share battles.

Concerns have mounted as the industry’s aggregate ASM growth has accelerated this year. And in October, in a meeting with Wall Street analysts, AMR’s influential CEO Don Carty blasted his rivals for irresponsible capacity addition. Since then he has also suggested that American’s own planned 3% growth may be excessive.

As Continental is the only one of the hub–and- spoke carriers growing at a 10% annual rate, its share price this year has been hurt by such concerns. Its price/earnings ratio (7.5 on 1999 earnings) continues to lag the average for the major carriers (9.4).

Consequently, at the end of October Greg Brenneman and CFO Larry Kellner gave a major presentation to shareholders and analysts in New York. The top executives explained why Continental is able to grow at such as rate and remain profitable. They also assured investors that growth would continue only if the 10% operating margin can be maintained.

The company also disclosed that it is pursuing new “high return, low–risk” opportunities that could add $875m to annual pre–tax profits by 2004. The benefits would come from further efforts in five areas: alliances, distribution costs, business mix, low–risk growth and fleet rationalisation.

Focus on “underdeveloped” hubs

All of Continental’s growth has focused on strengthening its main hubs at Houston, Newark and Cleveland. The carrier says that it has been able to grow so dramatically and profitably because all of those hubs have been “underdeveloped”, with spare capacity and a large potential local traffic base.

Continental is the only carrier that operates a hub for New York City, the world’s largest business travel market, while its home base Houston is the fourth largest city in the US. Cleveland is very underdeveloped relative to the size of the city — it has only one–third of the departures of Cincinnati (a secondary hub for Continental) even though the local market is twice as large.

The desire to grow is understandable in the light of the long pre–1997 stagnation period. Over the past 10 years, Continental’s ASMs have increased by just 1.1% annually, compared to the industry average of 3.4%.

The airline is now making up for the hub–building opportunities missed in the past and has been investing heavily to improve facilities. It seems very likely that American would follow exactly the same strategy, were it fortunate enough to have such good growth opportunities at its hubs.

Having large local traffic bases at hubs is a blessing for Continental as such traffic tends to mean higher yields. About 64% of its total traffic originates in one of its hubs,compared to about 48% for the industry. There is virtually no linear flying — all future growth will be out of the four hubs. Another positive is a relatively diversified international network by US carrier standards.

Domestic operations account for 64% of revenues, Europe 16%, Latin America 12% and Pacific 8%. This reduces the risk of being too badly affected by problems in any particular region.

But JetBlue’s plans to start Southweststyle low–fare operations from New York’s JFK in early 2000 are bad news for Continental, as the new carrier has ambitious growth plans and, thanks to strong initial funding, much staying power. It will sell itself as New York City’s only homegrown airline, offering high–quality service from a more convenient airport, and therefore pull both leisure and business traffic away from the majors. A mid–October report from PaineWebber estimated the profit impact on Continental at a modest 20–30 cents per share in FY 2000, when the venture is still in its start–up phase.

Continental’s latest five–year projection calls for growth in daily jet departures from the current 1,373 to 1,850 in 2004, assuming that profit margins will allow it. The general theme is more frequencies out of all hubs and the use of slightly larger aircraft.

Latin American expansion looks set to continue, as allowed by ASAs, with new service to Brazil and Argentina, particularly now that unit revenues on US–Latin America routes have improved progressively this year.

Thanks to previously “outstanding” profit margins, Continental has grown dramatically on the transatlantic in recent years. It has identified further profitable expansion opportunities to 30 European cities (currently 17) over the next five years. Many of them are secondary cities that could be linked with Newark utilising the 767–200ER.

But those plans will have to wait as excess industry capacity caused Continental’s transatlantic unit revenues to plummet by 15.2% in the September quarter. Although the routes are still profitable, there is a need to rationalise.

Much of Continental’s ASM growth this year came from the new Tokyo routes, so next year’s growth was never expected to be that spectacular.

But the carrier and its Continental Micronesia subsidiary have now decided to retire six DC–10–30s earlier than planned (between now and next summer), so reducing planned ASM growth in 2000 from 6% to around 4.6%. The DC–10s will be replaced 757s, 737–800s and 777s.

Flexible fleet plan

The five–year fleet plan has much flexibility built in to allow Continental to regularly review the growth rate, based on profit margins. It has the option of keeping the fleet at the present level of 365 aircraft or even reducing it to 332 by accepting only committed deliveries and returning older aircraft when leases expire. Or it could grow dramatically, to 502 aircraft by 2004, by exercising all the options.

The carrier is in the process of rationalising and modernising its fleet, which last year still included nine different aircraft types covering virtually the full range of jets offered by Boeing. The number of types has now been reduced to six and is planned to go down to just four by 2003.

Over the past two years Continental has brought in 143 new Boeing aircraft (14 777s, 21 757s and 108 737s) and retired a similar number of older aircraft. By year–end its average fleet age will have fallen to 7.6 years — the lowest among the major carriers. The 777 was introduced a year ago and is utilised on the new Tokyo routes and a growing number of transatlantic sectors previously served with the DC–10. Deliveries of the 767–200ER and 767–400ER will begin in 2000 and will enable the DC–10 retirement process to be completed over the next few years.

The commonality benefits associated with moving from six to four aircraft types are estimated to boost pre–tax profits by $125m annually, and on top of that there will be major cost savings through increased fuel efficiency and productivity.

Financing costs have been reduced by securing an average interest rate of less than 7% on the $4.6bn worth of deals completed since 1997. All of that is long–term debt or leases, so the benefits will be felt going forward as far as 10–15 years.

The five–year plan does not cover regional subsidiary Continental Express, which is expanding rapidly and moving towards an all–jet fleet over the next few years. It launched the 50–seat ERJ–145 in 1997 and the 37–seat ERJ–135 in September, becoming the first North American operator for both types.

Alliance benefits

Continental’s leadership considers the current worldwide alliance network to be essentially complete. The latest five–year projection envisages the addition of just two more partners, to bring the total to 20 by 2004. However, there is a long way to go to realise all the benefits.

The Northwest alliance has so far exceeded the financial projections made a year ago. It is expected to contribute $70m to Continental’s bottom line this year. The two have now linked most of their domestic and international routes and exchange about 2,000 passengers per day. Cooperation has proved particularly useful on the US–Tokyo routes — a market that Continental entered a year ago with service from Newark and Houston. When fully implemented, the pretax benefits derived from the alliance are expected to amount to $200–225m annually. But Continental is concerned about the disparity in service standards. It has an award–winning product, whereas Northwest’s still leaves much to be desired. Developing a consistent product will be one of the biggest challenges faced by the alliance.

Continental has also implemented code–sharing with Northwest’s partners Alaska and Horizon, focusing on the West coast and Pacific Northwest routes. And it recently expanded its extensive domestic code–sharing deal with America West to cover eight markets in Canada and Europe.

Like its competitors, Continental has been active in forging alliances in Latin America. Its partners there now include VASP, Copa, ACES, Air Aruba, Aserca (Venezuela) and AVANT (Chile). The deals were prompted either by an investment opportunity (Copa) or a desire to secure some local or regional feed to new services to the region.

Although the 1993 alliance with Alitalia has been expanded and is described as “very successful”, the impression gained is that there is nothing very substantial on the horizon. The late October New York gathering was told, in response to a question, that “we may be the only airline in the US that really does not need a European partner, because we can fly to so many cities out of New York”.

This, of course, reflects Continental’s desire to operate nonstop services, which passengers prefer, to as many cities as possible. It will still need the feed from elsewhere in Europe, as well as the Middle East and Africa, provided by partners. Improving business mix The business traveller content of Continental’s traffic has risen steadily, from 37% of revenues in 1995 to about 45% at present. The carrier has set the target at 50% by 2004 — a level enjoyed by American, Delta and United. Reaching that would generate an additional $175m in annual pre–tax profits.

The way to get there is apparently through corporate contracts, and the alliance with Northwest is expected to help. By jointly bidding on such contracts, the two can offer a much larger network centred on more hubs.They have already signed up three large corporations and have 20 more in the pipeline. Continental executives stress that the Northwest alliance is crucial in enabling it to compete with the three biggest carriers . Reducing distribution costs Efforts to cut costs by eliminating inefficient distribution methods have been equally successful. Since 1994 Continental’s sales and distribution expenses have declined from 17% to 14.3% of passenger revenues. E–tickets now account for 42% of total sales, compared to 1% in 1995.

The recent travel agency commission cuts are estimated to save Continental $90m per year, of which $15m will be invested back into the distribution system. The distribution cost percentage is expected to fall to 10% by 2004, generating $200m annual pre–tax benefits. This figure assumes some penalties, including some form of compensation to travel agents and lower ticket prices on the Internet.

Like its competitors, Continental is now aggressively pursuing Internet sales — whether on its own web site, industry travel sites or through companies like Priceline. It has just joined forces with United, Delta and Northwest to launch a new independent travel site in the first half of 2000.

The purpose of web sites is to get more direct bookings, thus eliminating CRS fees. In the third quarter Continental’s web site generated $52m in sales. The carrier believes that 20–25% of the market is willing to buy on its the web site if it can offer the lowest fares there. Once the site is ready to handle that, maybe by mid–2000, growth could really take off. By 2003 Continental expects its Internet sales to have reached $2bn annually or 20–25% of total sales.

Labour cost challenges

Continental continues to enjoy excellent labour relations, in part because of the ongoing process of restoring wages to industry standards (the average of the top ten carriers) by July 2000. Two years ago it essentially gave in on economic issues in difficult contract talks with the pilots. It also pays generous amounts in profit sharing and takes care to treat unionised and non unionised employees equally.

As a result, it has avoided further unionisation. Its fleet service workers recently overwhelmingly rejected IAM’s efforts to organise them. And current contract talks with the flight attendants are apparently going well (albeit under federal mediation) and should be concluded by the December 24 deadline or early in the new year.

Contracts with other worker groups will not become amendable until 2002 or 2003. But the price paid for the tranquillity are substantial hikes in labour costs. Wages and salaries surged by 22.3% in 1998 and 17.7% in the first nine months of this year. How will the 10% operating margin be maintained in the face of such pressures?

First, Continental believes that the existing contracts will allow it to maintain a labour cost advantage through productivity.

Second, there are continued efforts to eliminate non–value–added costs. Those factors succeeded in limiting the September quarter’s hike in unit costs (excluding fuel) to just 0.1%, and the current quarter’s increase will be less than 1%. The percentage for the year will be a little higher, but only because of extra training costs associated with the fleet transition in the first half of the year. Unlike its competitors, Continental knows exactly where its labour costs are going to be. There will be no unpleasant surprises. The 10% operating margin is believed to be a reasonable goal, representing an average of perhaps a 8–12% range.

Like Delta, Continental has been shedding some of its non–strategic assets. The sale of Amadeus, which closed in late October, will result in a $296m pre–tax gain in the December quarter. The company has an ample $1.7bn in cash reserves, and now intends to return some of it to shareholders. It has just announced an increase in its share repurchase scheme, which began in 1998, from $800m to $1.26bn. In an unusually generous move, the board authorised the company to use half its 2000 net earnings, plus all proceeds from future non–strategic asset sales, for additional stock buy–backs.

| A300 | A320 | 747 | DC10 | L1011 | MD11 | |

| Air Atlanta Icelandic | 11 | 4 | ||||

| Atlas Air | 30 (5) | |||||

| Gemini Air | 11 | (2) | ||||

| TransAer | 6 | 11 | ||||

| World Airways | 3 | 8 | ||||

| TOTAL | 6 | 11 | 41 (5) | 14 | 4 | 8 (2) |