Wet-lease airlines: from occasional business to profitable niche

December 1999

Wet–leasing of aircraft — complete with crews, maintenance and insurance — to other operators is not a new development. It has been around for almost as many years as airlines have been flying, largely as a means of overcoming temporary shortages of aircraft in order to maintain scheduled or charter passenger services. What is different in today’s environment is the increasing number of airlines, which focus either entirely — or almost entirely — on providing wet–lease services. All but one of these have come into existence since 1990.

So, what has changed to turn this occasional business into a full–time and profitable enterprise, with new entrants on both sides of the Atlantic? The answer lies in the relentless and increasing drive by airlines to cut costs, and to balance the conflicting objectives of scheduled operations to maximise yields against maintaining capacity.

Air Atlanta Icelandic

In an increasingly competitive business, airlines can no longer afford to add further high–cost aircraft and infrastructure when the expected returns are uncertain, or at best minimal. This particularly applies to the development of new routes, where wet–leasing an aircraft significantly minimises the risk of fixed–cost investment. "This is where we are able to come in and provide a good reliable passenger service, at much lower cost," says Magnus Thorstenn, chief executive of Air Atlanta Icelandic, "we are problem solvers and have the flexibility to respond at short notice." Such notice can be from as little as days, as in the case of its recent contract with Iberia, but three months is a more normal target, in order to increase the chances of finding a suitable aircraft to meet the customer airline’s requirements. Along with other airlines offering almost exclusively wet–leasing services, Air Atlanta Icelandic has a big advantage in that it does not compete directly or indirectly with its customers.

Around 96% of its contracts are on an ACMI (aircraft, crews, maintenance and insurance) basis, where the customer airline bears all other operating expenses, including fuel, landing fees, and passenger and aircraft handling. Aircraft can be painted in the customer’s livery, crew can fly in customer uniforms, and the level of cabin service can also be tailored to the customer’s requirements. Air Atlanta Icelandic provides station operations staff and engineers with each aircraft, maintains a spares depot and workshops at Manston in the UK, and is looking towards setting up a similar facility elsewhere in the world.

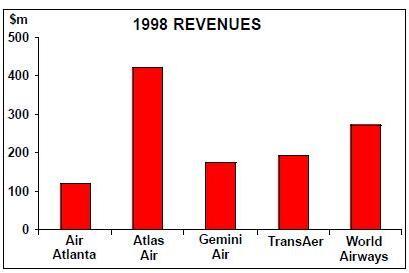

It presently has aircraft in service with Iberia, Air Afrique, Air–India and Saudia. Two cargo 737s, one flying with DHL, the other Lufthansa, have been sold, as the airline moves to an all–passenger operation. On the passenger side, Air Atlanta Icelandic is believed to be the only airline deriving its income solely from wet–lease operations, although there is no shortage of competition from companies operating a mix of wet–lease and own scheduled or charter services. In 1998, Air Atlanta Icelandic had revenues of $120m and made a profit, although Thorstenn will not reveal just how much. But with only two years of losses (during the recession of the early 1990s) in its 13–year history, the concept clearly works.

TransAer

Most prominent among the competition is Irish company TransAer, which has carved out for itself a niche market with a fleet based on A320s. Its most recent contract, for a period of 18 months, was signed with Cubana, and involves flying two A320s on schedules from Havana to points in the Americas. The $30m deal brought the value of contracts won in 1999 to over $130 million.

Other major clients which have availed themselves of the TransAer ACMI service include Air Canada, Air France, Aer Lingus, Britannia Airways, Malaysia Airlines, Sabena and Virgin Atlantic. Revenues in 1998 came to $195 million, with around 60% derived from ACMI work, the rest from its own charters. Total flying hours reached 44,000.

Atlas Air

There are other drivers in the freight sector of air transport. Few of the world’s leading international airlines now operate dedicated freighters, having abandoned these as cargo capacity in the bellyhold of widebody passenger aircraft increased sufficiently to meet demand.

However, as airlines are replacing high capacity aircraft with smaller types to meet changing passenger flows, and with freight traffic rising and expected to outstrip passenger growth in the years ahead, airlines will need to re–deploy pure freighters. Wetlease airlines can offer a more cost–effective alternative to taking on the required capacity through the heavy financial commitment of purchasing or leasing new aircraft and establishing associated infrastructure.

US company Atlas Air, founded in April 1992 by Michael Chowdry, has taken full advantage of this trend and of the availability of early model 747–200s, which are being replaced in mainline fleets by new technology, often twin–engined aircraft.

Its 18–strong freighter fleet operates under ACMI contracts for British Airways, China Airlines, Emirates, Alitalia, Fast Air, KLM, Korean Air, Lufthansa, SAS and Thai International, serving more than 100 destinations in nearly 50 countries. In terms of cargo carried, Atlas Air is now the world’s third–largest cargo carrier, behind only Federal Express and United Parcel Service.

This is an impressive performance in a new niche market, which has won Chowdry the 1999 National Ernst & Young Service Entrepreneur of the year award.

The Atlas Air strategy is simple. Its focus is on maintaining a low–cost operating structure that enables it to offer its services at rates, which are significantly lower than the airline customers' own internal costs.

Central to this strategy is its emphasis on long–term (typically three years or more) contractual arrangements, which provide guaranteed revenue levels, even if load factors fluctuate widely. For this reason, it generally rejects short–term or 'fill–in' business. Revenues and costs are in US dollars, also enabling the company to avoid currency fluctuations when conducting business abroad.

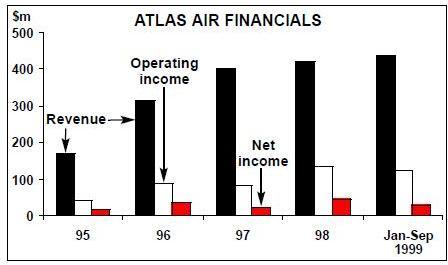

Steadily–rising revenues reached $422m in fiscal year 1998. This figure has already been exceeded in the first nine months of 1999, when the airline reported revenues of $438m. This represents a 60% increase on the revenues achieved in the same period in 1998, in spite of the negative impact on its operations of hurricanes and the earthquake in Taiwan.

Revenue per block hour increased to a record $5,855. Net profit in fiscal 1998 came to $46m; $29m was posted to 30 September 1999, a marginal improvement over the previous nine–months. Richard H Shuyler, executive VP, says that, with record cargo volumes and full utilisation of its fleet, the company should achieve a "positive finish for 1999."

Gemini Air Cargo

Although Atlas Air is the undoubted market leader, operating 12% of the world’s freighter fleet, competition is being mounted by another US carrier, Washington–based Gemini Air Cargo, which flies 11 DC–10–30F aircraft on ACMI contracts for some of the world’s leading airlines. The fleet will be increased with the addition of two MD–11s, to be leased from Gecas in May 2000 and converted to freighter configuration. The company did not start operations until December 1995, but has already made an impact in the market.

World Airways

Established longest in this business is World Airways, whose history goes back to 1948, but with its parent WorldCorp filing for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection last February, its long–term future remains unclear. While it has ventured from time to time into scheduled services, it has largely remained faithful to its three core businesses, which include charter, ACMI, and government contracts.

Prospects

Passenger and cargo ACMI accounted for a large part of its 1998 revenues of $271m, but higher fuel costs and lower passenger ACMI, especially for customers in Asia, are expected to further depress revenues and keep losses around the $10m mark. World operates a fleet of five MD–11 passenger aircraft and three MD–11F freighters. Its DC–10–30s are being sold. Present customers are Aer Lingus, Malaysia Airlines and STAF. The growth of the fleet is entirely dependent on contracts won. In this business, Air Atlanta’s Thorstenn emphasises, there is no place for speculation. Aircraft are rarely, if ever, brought in on vague possibilities, and then usually in ones and twos on the second- hand market as required.

This makes Atlas Air’s acquisition of 12 747–400Fs a quite remarkable departure from the norm, but the company says that customers have been lined up for all of these. Yet, adding aircraft remains a fine balancing act, especially in the passenger market, in that follow–on work has to be found to maintain revenue flow, although as contracts get longer — three years is not unusual — the risk factors are coming down.

Widebody aircraft, especially first–generation types such as the Lockheed TriStar, the DC–10 and early Boeing 747–100/200Bs, dominate the fleets. This, says Thorstenn, is a reflection of customer demand for high capacity aircraft, availability, and cost limitations, although if the customer is prepared to pay the higher price, newer aircraft can be obtained.

Given the relative uncertainty of contract work, it is remarkable that fleet utilisation is up to the levels achieved in normal year–round airline operations. Two of Air Atlanta’s fleet on long–term contracts are logging the equivalent of 4,000 hours/year, with a fleet average of 2,000–2,500 hours.