Exponential growth in use of Internet

December 1999

Airlines' use of the Internet to sell tickets is growing exponentially — both through their own web sites and through specialised travel and on–line auction web sites such as Travelocity.com and QXL. Not to be left behind, the CRS/GDS are now also entering the Internet market. The big losers are the travel agents.

For passengers with a complicated itinerary, who are not computer literate, or just do not know where they are going, the travel agent however remains important. But travel agents will increasingly have to sell their services as travel consultants, charging the passenger directly rather than indirectly through commissions on airline tickets.

Airlines have little choice but to sever their traditional relationship with agents as they focus on reducing distribution costs and increasing the percentage of direct sales (which used to be stuck at about 20% of the total). In the US, where Internet penetration has reached about 6% of total ticket sales, it is estimated that the cost of selling a ticket via the Internet is about a quarter that of selling it via a travel agency. As an indication of how rapidly Internet bookings could grow, today some 45% of US passengers use some form of e–ticketing when making travel arrangements.

Sales via the Internet give an airline greater control — more than half of the tickets sold on–line will be through the airline’s own web site. Sales made through an airline’s own web site also allows the airline to understand better the characteristics of its passengers, to directly target them and to pamper their best customers. The Internet is also a cheaper and faster way of conveying news and offers to frequent fliers than direct mailings.

US airlines are also willing to pool their resources on the Internet. Delta, United, Northwest, and Continental are participating in the first multi–airline travel portal. This site, which is independently owned, is due to start up next year.

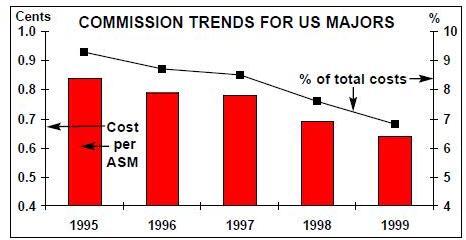

As airlines gain more confidence in using the Internet as a distribution tool, they will be even more aggressive in putting pressure on travel agents to reduce commission rates (they are also alienating agents by offering fares and availability on their own web sites which are available to the agents themselves).

European airlines are inevitably trailing the Americans, but they are becoming increasingly aware of the opportunities presented by the Internet. For instance, in mid- November British Midland began a four–week Internet auction offering 10,000 tickets to 30 European destinations. BMA is selling the tickets through the Internet auction company QXL. About 350 tickets are sold each day with the auction open from 1400 hours each day for 24 hours. BMA, rather than set up its own web site, has preferred to pay QXL a commission.

EasyJet has dispensed with travel agents altogether. The airline relies either on prospective passengers calling the airline directly, or using the Internet to book tickets through the airlines web site (now some 60 % of sales). EasyJet’s web site is, well, easy — clearly laid–out, quick to navigate and relatively idiot–proof. When easyJet divulges more detailed financial information, it will be interesting to see how much the site costs to maintain.

The Internet also provides a way for airlines to sell so–called "distressed inventory", unwanted seats on unpopular routes, usually in the low season. One problem is that the high level of publicity that these auctions attract — recent headlines highlighted £1 London–Dublin return fares — and the consequent disgruntlement of full fare passengers.

GDS disposals

In Europe airlines have enjoyed windfall profits from the sale of stakes in their GDS. British Airways gained a net £42m ($70m from the sale of its stake in Galileo and the IPO of Amadeus will bring one–off financial gains for Lufthansa and Air France.

When explaining these sales airline tend to emphasises these points:

- GDSs are non–core activities;

- Now that all GDSs carry the same unbiased information they offered no competitive advantage to the airline owner; and

- Selling off these systems raises cash for fleet renewal and other forms of capital expenditure.

However, the fundamental reason may be that airlines see a conflict between developing their own web sites whereas the future of GDS appears to lie in producing different web sites for the distribution of airline tickets.

The problem for the GDSs is that their prime source of revenue is bookings made through travel agents. Each of the three major GDS carry, by law, identical data regarding flight schedules and availability, so the main differentiation factors that will sway a travel agent to use a particular GDS are acquisition price and fees thereafter, ease of use, and customer satisfaction regarding technical innovations etc.

Until recently, the three GDSs have chased market share on this basis, the key to the success being, as James Bartlett the CEO of Galileo put it , "distribution, distribution, distribution". Thus Galileo’s main thrust has been to buy out control of the national distribution companies, and to focus expansion into new markets for example in Eastern Europe and the Africa.

Galileo has 36,000 travel agency users worldwide, and the third quarter 1999 results showed a 6% increase in net income to $54.2m. Morgan Stanley suggests that income growth might average 15% p.a. in the future, which is pretty good by aviation standards, but nothing compared to the phenomenal growth expected for Internet distributors like Priceline.com. (actually there has to be phenomenal growth to justify the huge stock–market valuations of these e–companies)

Perhaps this partly explains why Galileo has gone from stating that it has "no plans to enter" the online market to announcing two new web sites. The first of these sites allows the airlines to sell tickets commission free but in return must support the site (presumably financially) and offer their best pricing and web products. This site obviously allows the airlines to sell tickets through the Galileo and cut out the middleman/ travel agency and the commissions. This is a brave step for Galileo as it potentially undermines its clients' revenues.

Thus in a sop to travel agents, Galileo has announced plans for a "super travel agency site". The aim of this site being to allow travel agencies to gain access to the discounted fares that are currently only available through the airline and auction type web–sites.

The difficult decision for Galileo and Amadeus is to whether to follow Sabre’s lead and invest heavily in the Internet at the potential risk of upsetting the travel agents.

Sticking with existing formula allows access to a growing market for airline passenger bookings of roughly 5% p.a., but a market whose fundamentals are under threat by the increasing use of the Internet by individual passengers and businesses booking directly online either on airline web sites or through sites such as Travelocity.com or Priceline.com.

Online travel agencies

There are two models of online travel agencies, or Internet agencies. The first is basically an electronic version of the traditional travel agent, the largest of which is Travelocity.com. Indeed, it is now the 19th largest travel agency in the US. The web site carries booking information on over 42,000 hotels and 50 car rental companies.

Travelocity.com is owned by Sabre which in turn is 82% owned by AMR Corp.. It has arrangements with various airlines in addition to American and generates commission revenue of between 4–5% of the value of travel purchased at the website.

Travelocity.com announced in October that it was merging with Preview Travel, which has links with service provider AOL. The combined company has projected sales revenues of $1bn for 1999 and with a membership base of 17m people, a 50% size advantage over the next largest Internet agency. The five–year growth rate in gross travel sales is estimated at over 300%.

The second model is represented by Priceline.com, which is a quoted company on NASDAQ, and has Delta as a shareholder.

It currently enjoys a remarkable stock–market capitalisation of over $8bn. Priceline.com purchases tickets in bulk from carriers such as Delta, Northwest, America West, TWA and Midway. These are then sold at its website. Customers are asked to make a bid for tickets, and if Priceline.com accepts their bid, the customer is contractually bound by his/her offer. Reminiscent of "bucket shops" in Europe, Priceline.com is a good place for airlines to dump excess capacity and a good place for passengers to find cheap tickets.

Priceline.com may offer cheaper fares than Travelocity.com but it offers the traveller less convenience. A Priceline.com user has no control over departure times and connectivity, thus routings can be highly circuitous.

Priceline.com’s third quarter results for 1999 showed revenues up from $9.2m to $152.2m and net losses reduced from $102.2m to $19.9m. During this period Priceline.com sold a total of 624,000 airline tickets and 180,000 room nights. Although tickets and hotel beds are not the only things that can be purchased on the website, Priceline.com also sells mortgages and cars. The stock market consensus forecast expects Priceline.com to deliver 75% earnings growth in the next few years.

The Internet as a distribution source, by airlines, on–line agencies and by GDS has and will continue to marginalise the traditional travel agencies. The future of travel agents depends on whether they can demonstrate they are adding value in the supply chain between the airline and the passenger.

Worse still for travel agencies would be if tour operators also develop direct online sales, offering customers the opportunity of buying the various elements of a holiday — flight, hotel, car hire, etc. — via the Internet. At present the travel agencies appear to be protected from this development because of the vertical integration of the business, with tour operators owning travel agencies. But at some point, the tour operators may welcome to view the travel agencies as dispensable (just as airlines realised that their GDSs were no longer essential).

UPS: SUPER-CARRIER OF THE INTERNET

In the October issue of Aviation Strategy we commented, a little sceptically, on Federal Express’s image as the "official airline of the Internet". However, the part–flotation of UPS stock in November has provided an even more dramatic example of how investors expect integrated cargo airlines to benefit from the growth of e–commerce.

The stock–market is valuing UPS as around $84bn, representing a price/earnings ratio of about 50. It is now theoretically worth six times more than FedEx.

Although such a value cannot be maintained (can it?), this indicates that UPS has huge resources available to acquire companies in the European and Asian markets, restructuring the fast cargo industry outside the US on its own.

| Third quarter: | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 |

| E-ticket sales as | |||

| percentage of total | 19% | 32% | 42% |

| Web site sales | $4m | $18m | $52m |