Sabena - Europe's first flag-carrier failure?

December 1998

Of all the problems that could possibly face a European airline as it entered the 1990s — poor service, union unrest, low load factors, a diverse fleet, unprofitable short–haul, weak longhaul — Sabena faced the lot. As the millennium approaches, how far has Sabena progressed in overcoming these problems and ensuring its long–term survival?

When Pierre Godfroid was appointed president in of Sabena in 1990, the task he faced was immense. The Belgian government gave him three core targets — restructuring the airline, preparing the company for privatisation, and recapitalisation.

Godfroid initially made good progress. The 'Phoenix' restructuring plan cut the workforce by 3,500 to 9,500 by 1994, while in April 1992 Air France pumped BF6bn ($187m) into Sabena in return for a minority stake. The Belgian state ‘invested’ another BF9bn ($280m), increasing Sabena’s capital from BF1.1bn to Bf16.1bn ($500m). Strategically, Godfroid regrouped the airline’s activities into two major areas — Europe and Africa (where the airline has strong ties historically) — while in Europe a hub system was built up at Brussels in three waves per day.

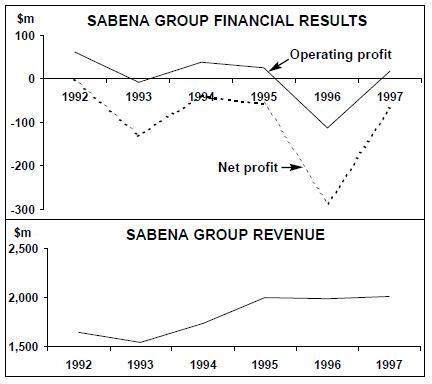

Yet Godfroid’s efforts were not enough. In 1993 the airline plunged into loss (see graph, right) and Air France withdrew from Sabena in 1994, to be replaced by Swissair, which took a 49.5% stake in July 1994 (the Belgian government and other domestic investors hold the balance of the equity).

And so another optimistic era began for the airline. This time around, the goal was for Swissair/Sabena to become the third most important airline grouping in Europe by 2000 (after Lufthansa and British Airways).

To do that, however, meant breaking the power of the unions. In November 1995 the airline cancelled all labour agreements with unions, leading to immediate strike action. The dispute was inevitable given that Godfroid was determined to abolish the airline’s salary indexation system (introduced in the 1960s) via a three year salary freeze, along with an increase in the working week from 38 to 40 hours. The carrot was another 1,000 jobs and a profit–share scheme worth 25% of the profits. But union uproar at the move and a damaging strike eventually led to the resignation of Godfroid. In April 1996 Swissair appointed Paul Reutlinger as his replacement.

Reutlinger’s task was clearer than the one given to Godfroid — cut costs by BF4.7bn ($150m at the 1996 exchange rate) by 1998. Reutlinger’s policy was unveiled in June 1996: he gave the unions three choices — a 12% salary reduction, 1,270 job losses, or revised work schedules. Any one of these would reduce labour costs by BF2bn ($64m). The other BF2.7bn ($86n) saving was to come via restructuring (i.e. fleet rationalisation,closing unprofitable routes, adding destinations, improving the brand, developing the Brussels hub, and even spinning off cargo and catering).

If these savings could be achieved, the airline would at least break even by 1998 — dubbed the Horizon 98 scenario. There are further ambitious targets of a 4% ROC in 1998, rising to 8% by 2000.

Not surprisingly, the unions were not happy with the choices they were given, but in October 1996 a deal was eventually agreed. Instead of implementing any one of the three choices in full, the agreement included parts of each — an average 2% salary decrease, the loss of 730 jobs via early retirement and voluntary redundancy, and some flexibility in working hours.

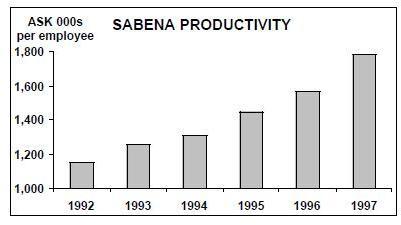

Whether this deal will deliver the projected BF2bn in savings in 1998 is difficult to judge. Productivity has risen significantly over the last few years (see chart, page 17), but productivity is a moving target. Benchmark European airlines such as BA are improving their productivity all the time, and Sabena seems destined always to be playing catch–up. For example, Sabena’s workforce was still larger in 1997 than in 1994, and despite the job cuts an increase in ground handling staff means that Sabena’s overall workforce will fall by just 300 in 1998.

Other than labour, Reutlinger is still looking for BF2.7bn worth of cost savings in four key divisions — cargo, catering, ground operations and technical. Particular progress has been made in one area — fleet rationalisation.

Fleet progression

Sabena’s efforts at fleet rationalisation are finally starting to take shape. On short–haul, 28 737s will be replaced directly by 28 A319/20/21s over 1999–2001, with another six A320 family aircraft being used for extra frequencies and new destinations. Unions originally objected to Sabena’s plans to replace all Boeings in its fleet by 2000 (so ensuring fleet harmonisation with Swissair and Austrian) as they feared losing significant 737 maintenance work. However, Sabena’s management promised that Airbus maintenance would be carried out by the airline’s subsidiary Sabena Technics.

DC–10s and A310s have already left the widebody fleet, and the last two 747–300s will go in 1999. Three ex Air–Inter A330–300s arrived in 1997 — initially on five year leases, now extended to 10 years — and the A330–200 fleet will increase to six by the end of 1999. Along with A340s, the only other model in Sabena’s fleet after 2000 will be the MD–11, two of which are wet–leased from Belgian charter airline CityBird (in which Sabena has a minority stake). Overall, the fleet will have an average age of four years by 2000.

Reutlinger’s cost–cutting measures are now filtering through. There was still a BF2.5bn ($70m) net loss in 1997, but this was after exceptional charges of BF2.5bn. Turnover rose 16% in 1997, with a BF615m ($17m) operating profit. In the first–half of 1998 Sabena recorded a net profit of BF59m ($1.6m), boosted by a new five–wave system at the Brussels hub and extra long–haul services. Yet cost–cutting alone (the latest round is called ‘Fit for the Cycle’) — even if it is successful in helping the airline to break–even in 1998 — may not be enough to secure Sabena’s future.

Short-haul danger?

Central to Sabena’s European strategy is the outsourcing of loss–making routes to low–cost carriers. In October 1996 Sabena handed over its nine–flights–a-day service on Brussels–London Heathrow to Virgin Express, via a wet–lease of 737–300s. This was followed by outsourcing or block booking deals with Virgin Express on Brussels to Barcelona, Rome/Fiumicino, London Gatwick and London Stansted. And from April 1997 Antwerp to London Heathrow services were taken over by VLM, an Antwerp–based regional.

Sabena’s justification for the outsourcing is simply that these routes are loss–making — Brussels to London in particular has been affected by competition from Eurotunnel.

Sabena promised the airline’s unions that it would limit co–operation with low–costs to these destinations, as long as the unions allowed these deals to go–ahead unhindered.

With the Virgin Express code–sharing deals, Sabena sells only business class tickets, but both carriers compete for economy business. According to Sabena, the link with Virgin Express allowed Sabena to improve the bottom line by BF394m ($11m) in 1997. So although Reutlinger says that the Virgin Express tie–ups have resulted in losing high–yield business class passengers to competitors on the VE routes, that has been more than made up by lower costs and extra economy passengers via increased frequencies and lower fares.

This appears to be a dangerous strategy. If basic profitability on trunk routes was such a problem for Sabena in the first place (and London is Sabena’s most important route) then something was seriously wrong with the airline’s operations.

For Virgin Express, the Sabena deal has also proved problematical, as it has had to face the same union and cost problems that Sabena faced. And liaison between VE’s American management and Sabena’s Belgian executives has not been perfect either. On the other hand, Virgin does now have a stranglehold on some key passenger feed for Sabena. Furthermore, the loss of business–class passengers will impact long–term on Sabena’s profitability as they switch to other airlines’ long–haul flights.

How Sabena believes it can maintain any kind of business–class brand while asking executives to fly on low–cost feeder airlines is difficult to comprehend. In 1997 overall traffic at Sabena increased by 30% — but economy rose by 39.8%, and business by just 7.5%, so overall yield was hit. The problem for Sabena is that it does not have a substantial long–haul network that can provide a steady stream of profits to make up for short–haul losses. Although Sabena is building up its long–haul routes, in the short- and medium–term it has no alternative but to try and make a small margin on short–haul, or at least scale back losses. This has been achieved by short–haul outsourcing. But this a short–sighted strategy on Sabena’s part because although it helps achieve the short–term goal of breaking even, the disadvantages of outsourcing — the loss of key business feed — will impact severely on the airline’s long–term future.

The long-haul gap

European traffic accounts for 85% of Sabena’s total traffic, and its long–haul network lags well behind that of its major European rivals. The exception is Africa, where Sabena serves 17 destinations, making it Europe’s top carrier to that continent. Elsewhere the long–haul network is sparse — a handful of destinations in North/South America (Sabena code–shares with Delta to/from Atlanta, New York, Boston and Chicago, and with regional airline Comair to seven mid–west US destinations) and a few in the Asia/Pacific region.

In November 1997 Sabena bought a 11.2% in Belgian start–up CityBird, which now operates some long–haul routes for Sabena. But although Sabena has an option to increase its stake in CityBird to 25%, CityBird’s operations are also a signal to others that there is plenty of scope for new long–haul services out of Brussels.

Sabena did increase long–haul capacity by 11% in 1997, and further routes are planned — particularly to India and China — but the long–haul network will remain weak for some time yet.

Some compensation for Sabena’s long–haul weakness is the Brussels hub — its key asset — at which the airline has an estimated market share of 42%. Sabena serves the hub with five waves of flights per day, and has introduced a ‘Minimum Connect Time’ of 30 minutes. (Delta Air Transport, Sabena’s regional subsidiary, plays a major role at Brussels.)

But other European Majors are eyeing Brussels too, particularly for its substantial business class flow. If other airlines followed CityBird’s example on long–haul and Virgin Express’s example on short–haul, Sabena would be hard–pressed to maintain its share at the Brussels hub. Yet Sabena’s future is tied to Brussels, even if Belgium has high tax rates and social charges (estimated at 30% of salary costs).

Has restructuring gone far enough?

The key question for Sabena is whether the changes implemented by Reutlinger will be enough to turn the airline around? Despite all the good work on fleet restructuring and cost–cutting, Sabena is still faced with the problem that Belgium is a high cost base for any airline to operate in.

That’s why Sabena would like to base its pilots and flight attendants in Switzerland. Although planned for 1998, it hasn’t happened so far — but if Sabena could somehow achieve this relocation of 2,400 out of Sabena’s 9,800 staff, costs would be cut by an estimated BF1.5bn ($40m) a year. This is likely to make all the difference as to whether Sabena can break even or not before the millennium.

A realistic assessment, however, is that although the relocation is vital, Reutlinger’s plans are unlikely to succeed. A previous attempt by former president Godfroid to relocate pilots to Luxembourg failed, and unions are likely to resist the current plan unless they either receive something in return (which defeats the object of the relocation in the first place) or the airline is in severe danger of going under (unlikely, from the unions' viewpoint, with Swissair as the virtual majority shareholder).

And questions surely must be asked as to whether Switzerland gives much of a cost advantage over Belgium anyway? According to AEA data, social charges as a percentage of total pilot labour costs are about the same in Switzerland as Belgium, while salary and social charges as a percentage of total pilot labour costs are an estimated 30% higher in Switzerland than in Belgium.

Swissair’s stake in Sabena, and hence its wishes, are key. If Sabena is unlikely ever to contribute substantial profits in its own right — and some analysts argue that if it cannot make a profit in the current stage of the cycle, it never will — then its fate lies in its role within the Swissair/Delta axis.

Via Atlantic Excellence, launched in February 1997, Delta, Swissair and Sabena carry out integrated North Atlantic operations, with a revenue pool and access to all partner airlines’ seats. But this begs the question — what is in this alliance for Swissair and Delta? Although SAirGroup took over the marketing of Sabena’s (substantial) cargo capacity in January 1997, perhaps Sabena’s ultimate fate is to become the European short–haul specialist for Swissair and Delta. But is that likely if Sabena farms out key short–haul routes to Virgin Express and others? By handing the operation of key routes to/from the Brussels hub to low–cost airlines, Sabena has, in effect, surrendered valuable business class feed — which is surely the most valuable contribution Sabena could make to Swissair/Delta.

Of course Sabena can also offer its African network, but it is the Brussels hub that will be the key to Sabena’s future. If Sabena cannot keep a grip on vital business class feed for itself and/or alliance partners, its fate will decided, with or without successful cost–cutting.

Swissair may increase its stake in Sabena to 67% (by acquiring 17.5% from the Belgian government) if Switzerland joins the EU bilateral (as a non–EU based airline Swissair cannot otherwise gain full control). Reutlinger is reputed to operate Sabena relatively independently of Swissair, but that could all change if Swissair gains majority control. In particular, if Delta and Air France ally, then Swissair may prefer to jump ship and join the oneworld camp. This would leave Sabena in an awkward position.

A pointer to the future came in September 1998 when Sabena announced a new corporate structure, to be introduced from January 1999. There will be three business units — Airline, Brussels Hub (which includes ground and cargo handling) and Technics; and two main subsidiaries — regional airline DAT and charter carrier Sobelair. Each business unit will be given more operational accountability, and financial performances will be comparable.

This restructuring is a clear signal to the business unions to get their costs in order — but it also opens the way for clean and easy sales of one or more of the units in the future. One scenario is that when Swissair gains absolute control Technics could be sold off while the Airline business unit could be split, with some parts such as the African long–haul routes and key European feed routes being merged into Swissair.

| Hub | Connectivity ratio |

| Schiphol (KLM) | 1.8 |

| Brussels (Sabena) | 1.8 |

| Frankfurt (Lufthansa) | 1.6 |

| Paris CDG (Air France) | 1.4 |

| Rome (Alitalia) | 1.2 |

| Heathrow (British Airways) | 1.0 |

| Madrid (Iberia) | 0.9 |

| Rank | ||

| Score | in 1995 | |

| Lufthansa (Frankfurt) | 63% | 1 |

| Air France (Paris CDG) | 60% | 4 |

| KLM (Schiphol) | 59% | 3 |

| Swissair (Zurich) | 50% | 5 |

| British Airways (Heathrow) | 47% | 2 |

| Sabena (Brussels) | 15% | 10 |

| Alitalia (Rome) | 14% | 6 |

| British Airways (Gatwick) | 13% | 7 |

| Lufthansa (Munich) | 13% | 14 |

| All others | 10% |