The forgotten art of superior customer intimacy

December 1997

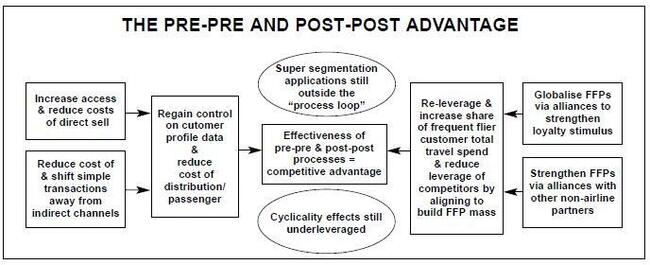

Expanding on the concept that airlines service consists of five segments — pre–pre–flight, pre–flight, in–flight, post–flight and post–post–flight (see pages 17–19, Aviation Strategy November 1997) — Louis Gialloreto takes a closer look at the pre–pre and post–post phases.

The pre–pre phase of the airline service process deals with those activities that stimulate a decision to select one carrier over another. These are normally referred to as market communications and the activities performed by the distribution channels. The post–post phase can be defined as all those activities designed to stimulate repeat business, and these occur after the customer has completed the service process on a particular trip.

Many might consider that these activities have always been rather traditional components of the overall service process. Yet in many airlines’ organisational structures these processes are separate and in many cases mis–focussed, even though the customer sees airline service (pre–pre, pre, in, post, post–post) as a single and optimally seamless process.

Airlines tend to see and structure each of their service processes as individual ones which, in the fullness of time, should culminate in an ever increasing pile of loyal repeat customers. Surely, however, it is time for the more enlightened managements to examine these parts of their overall service process more thoroughly.

Pre-pre: the fight to cut costs

With regard to the pre–pre–flight phase, airlines around the world have finally decided to deal with a key portion of their costs — travel trade commissions. Until 1994, this had been the single biggest unattacked cost pile remaining for airlines to downsize. However, because the industry has allowed undue concentration of power among third party wholesale and retail travel organisations, their ability to deal with these in any significant way has been greatly reduced.

Two solutions seem feasible. The first is the evolution of technology (such as the Internet), which has allowed for viable direct booking transactions, especially on simple type itineraries where travel retailers add little if any value. Direct booking via the Internet has the added advantage of presenting the airline with a customer information database. It is this information, in the proper format, that allows airlines to build value relationships with customers and therefore stem the tide back to the third party channels in any downturn.

The second solution, of course, is to reduce commissions. This process is already under way via flat fees and capping in the US, and is now winding its way into others markets (BA being the latest proponent). A variant on this is a uniform system of commission based on average yield/ticket sold in each distribution outlet. Many carriers have, at any given time, tried to implement such a system, with varying degrees of success.

Today, any carrier that has activated both these ideas and is trying Internet bookings as well as making the first step towards cutting commissions is ahead of 75–80% of the rest of the airline industry. But in tackling the pre–pre cost of commissions there must be some words of warning. Direct selling can catch airlines with inadequate technology and the expectation of lower fares can have a destabilising effect on customers’ expectations of airlines. Frustrated customers who try to book direct and fail are likely to fall back into the waiting arms of the third party distributor.

In addition, commission capping is a cyclical solution that works best when the market is growing. One can be sure that as soon as recession hits, weaker airlines will break ranks and abolish caps in order to garner travel trade favour and loyalty — as fleeting as this may be.

Post-post: the customer is king

The key question in the post–post phase is how to better handle and retain customers. Some airlines thought that the frequent flier programme was the answer, which of course it was for the first 18–24 months after introduction in many western markets. But when one airline’s FFP is matched by other airlines’ FFPs in any given market, then its advantages melt into an increasingly significant cost pile. That is unless an airline can mine this data–bank for the keys to long–lasting customer intimacy and enhanced revenue.

However, evidence of this mining is slim at best given the continuing propensity to let price drive the decision to purchase. In fact, FFPs are not tailored enough for the needs of differing types of frequent flier. The last recession caused the demise of many middle managers and thus thinned the FFP database of active fliers, and even given their replacement by nouveau fliers who are working their way up the mileage scale, the net effect is flat or even worse.

This depletion phenomenon is paired with the evolution of the frequent flier for whom the stimulus of the traditional FFP is becoming increasingly irrelevant. The average US frequent flier belongs to 4–4.5 FFPs, thereby watering down the effect of a single programme. These habitues place an increasingly large emphasis on better and more consistent service. This is compounded by travel weary FFPs who have more FFP miles than they could use in a lifetime of retirements.

This revised segmentation of infrequent; nouveau, very frequent and “worn–down” frequents should allow an airline to understand what percentage of their loyalty is stimulated through FFP perks and what share is actually retained via better consistent service. For example, if an airline has a high share of very frequents and fails to live up to service perceptions then it should not be surprised at an outflow of customers.

But instead of attempting advanced database segmentation and acting upon the results, most airlines are busy aligning their FFPs with those of others in order to form a seamless global programme that will reduce if not eliminate FFP leakage due to lack of a global network for accumulation or redemption. The theory is that this re–leverages the current FFP investment and also raises barriers to entry to those who are unable to globalise their FFP. As is so often the case, however, the FFP is something with a life of its own, and most wonder at the ROI, real or implied, that it represents. As a whole the industry has failed to adapt to the evolution of the market and seems to forget that FFPs are now 10 years old at some airlines, and therefore need to be re–adapted and refocussed to add strong value, real or perceived.

Beside the FFP, the post–post phase of the airline service process has only one other traditional component — the infamous customer complaints department. BA tried to fill a gaping hole in the process when it placed video recording facilities in some arrivals lounges and baggage claim areas in order to record immediate feedback. However, because customers are in a hurry to de–process themselves once the aircraft comes to a full and complete stop at the gate, airlines are reticent about annoying them with surveys or other data–gathering methods. Yet in a way this is the critical phase, when one can defuse loyaltydestroying service disasters and celebrate unmitigated successes.

As the market upturn progresses the industry tends to minimise the importance of these issues because growth hides many evils, but come downturn airlines will again be seeking to retain market share. Very few airlines seem intent on using this upturn to build their quotient of customer intimacy. If airlines wish to evolve the way other service industries have, they should take these two phases more intimately into the overall service process, and use the levers implicit in these phases to drive intimacy and loyalty in non–traditional ways.

|

|

Seller |

Already Sold | Price | To Sell | Sale Date |

| Australia | FAC | 3 | $2.6bn | 19 | 1998+ |

| Germany | Gov | 5 | 1998+ | ||

| Argentina | Gov | 38 | 1997/1998 | ||

| Mexico | Gov | 35 | 1998+ | ||

| Uruguay | Gov | 1 | 1999 | ||

| South Africa | ACSA | 9 | 1998 | ||

| Japan | gov | 1 | 2005 | ||

| UK | 18 | na | |||

| Italy | 2 | na |