Cathay Pacific: CAAC's

'insular possession'?

Jul/Aug 2019

Hong Kong has been shaken by civil unrest over protests against legislative change, which morphed into demands for democratic reform, in the former British colony. The “One country, two systems” accord agreed in at the time of the 1997 British hand-over is being tested, and Cathay Pacific has been caught in the middle as the PRC attempts to impose control.

CEO Rupert Hogg nobly replied to a demand from the Civil Aviation Administration of China (CAAC) for a list of Cathay employees who had taken part in “illegal” protests by submitting a letter containing only his own name. A couple of days later Hogg was replaced by Augustus Tang, who had been CEO of HAECO, another Swire Pacific company.

John Slosar, chairman of Cathay and board member at Air China, issued this statement: “Recent events have called into question Cathay Pacific’s commitment to flight safety and security and put our reputation and brand under pressure … We therefore think it is time to put a new management team in place who can reset confidence and lead the airline to new heights.”.

We can add little to the interpretation of Hong Kong politics and the sensitivities of Sino-British disputes over the “insular possession” that the British seized in the 1840s, partly as a base for the opium wars, but we can throw some background light on the complexities of the present Chinese aviation market.

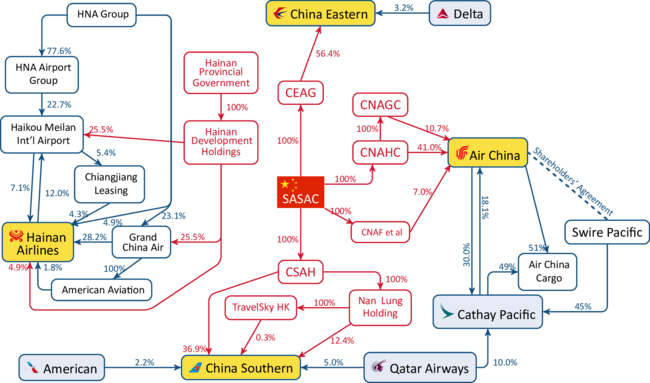

Nothing is more complex than the Chinese ownership web — shown. Although CAAC is the all-powerful regulator, almost the controller, of Chinese civil aviation, the Chinese ownership structure is centred on SASAC (State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission of the State Council), a state holding company which has stakes in just about every Chinese industrial group except banking. It has approval power for board appointments and mergers and take-overs. It may be the largest single entity in the world with assets estimated tentatively at the equivalent of US $30 trillion.

Its ownership of the major Chinese airlines is complicated as shareholdings are routed through various subsidiary holding companies, but it does have majority positions in the Big Three — Beijing-based Air China, Shanghai-based China Eastern and Guangzhou-based China Southern. It has a much smaller stake in Hainan Airlines which is part of the Hainan Province’s empire. HNA is in the process of selling its low cost subsidiary HK Express to Cathay, though Cathay CCO Paul Loo who was in charge in the transaction was exited at the same time as Hogg.

Cathay is linked to the official flag-carrier Air China (and hence to SASAC) in three ways — a shareholder agreement between Cathay’s parent Swire Pacific and Air China; a direct 30% stake in Cathay by Air China and a complementary 18% holding in Air China by Cathay; and a 49/51% joint ownership of Air China Cargo.

Western carriers are on the periphery of the web — American with a small stake in China Southern, Delta with a similar investment in China Eastern, which in turn has a stake in SkyTeam partner Air France. Qatar, naturally, has bought into region, with a 5% stake in China Southern and 10% in Cathay, a share which it has just stated it would like to increase.

The balance of economic power has shifted markedly mostly because of PRC’s super-growth but also a lack-lustre performance by Hong Kong in recent years: at the time of the handover, Hong Kong’s GDP was about 20% that of the mainland, now it is about 2%. Although volatile, the share price performance of the Big 3 relative to Cathay (see chart) reflects the Big 3’s expansion versus Cathay’s stagnation.

Measuring by stockmarket capitalisation reveals how Cathay is now eclipsed by the Big 3: as at late-August Cathay was valued at US $5.1bn, its partner Air China at US $15.0bn, China Southern at US $10.0bn and China Eastern at US $9.2bn.

Ironically, Cathay’s restructuring and expansion programme implemented under Rupert Hogg’s management team (see Aviation Strategy, March 2019) had started to show results. One of Hogg’s last tasks was to announce a net profit of HK $615 (US $74m) for the first half of this year compared to a loss of HK $904m in the same period of 2018. At the same time, Air China reported a net profit of RMB 3.1bn (US $434m) for the for the first half 2019.

More perspective

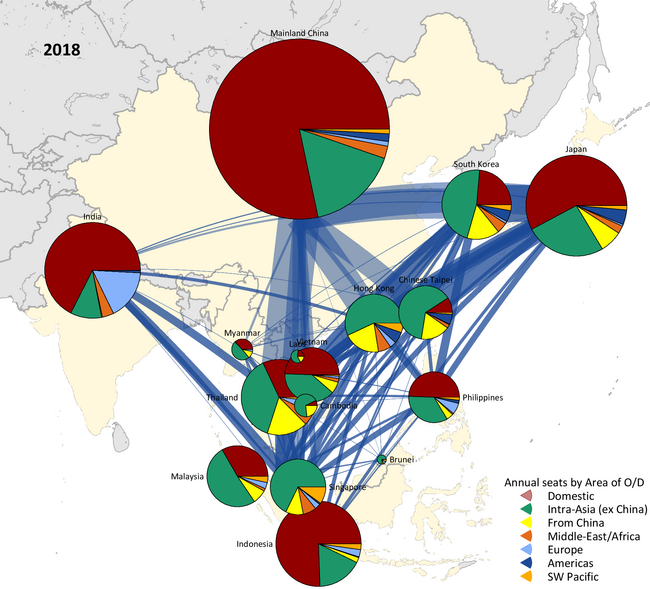

To put China’s aviation importance into perspective, this map shows intra-Asia seat capacity in 2018; the thickness of the lines and the area of the pie charts are directly related to the number of seats operated between the countries and to/from/within the country.

China dominates: the volume of Chinese traffic is more than three times that of Japan or India; its intra-Asian traffic is more than the whole of South Korea’s domestic and international traffic. Moreover, Chinese routes have, along with the emergence of Asian LCCs, been the key element in traffic development in fast-growing markets like Thailand and Indonesia and mature markets like Japan. Hong Kong is still very significant though the opening of Cross-Straits access between the PRC and ROC (Taiwan) has cut previously large volumes of transfer traffic.

Notes: SOSAC=State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission of the State Council; CNAHC=China National Aviation Holding Company; CNAGC=China National Aviation Group Company; CSAH=China Southern Air Holding; CEAG=China Eastern Airlines Group; CNAF=China National Aviation Fuel Company.