JetBlue: A220 key to

targeting superior margins

Jul/Aug 2018

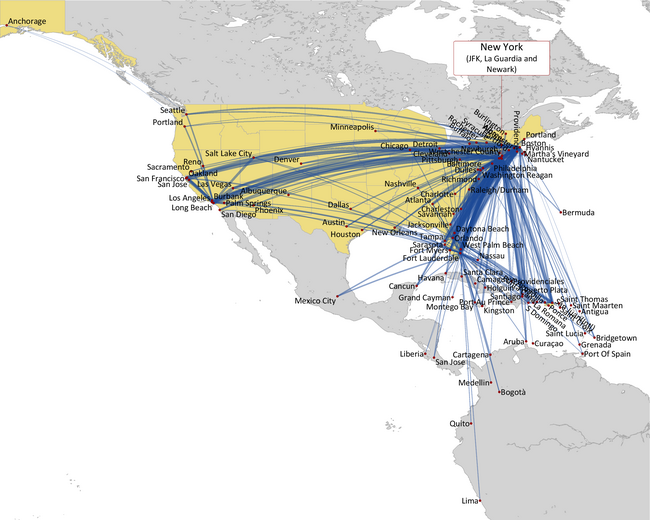

JetBlue Airways recently placed a major order for A220s, previously known as the Bombardier CSeries, as efforts move to higher gear to keep costs in check and attain long-term goals such as superior margins to its peers. When will New York’s hometown airline go for the A321LR and Europe?

Now in its 19th year, JetBlue has always been a revenue story. First, its everyday low fares, high-quality product offerings and service-oriented culture have enabled it to attract price premiums and considerable customer loyalty.

Second, JetBlue has been at the forefront of the US airline industry’s fare unbundling and cabin segmentation efforts, creating new revenue streams with offerings such as Even More Space seats, Fare Options and Mint premium product.

Third, JetBlue benefits from strong focus cities. To supplement its New York home base, JetBlue spotted opportunities from legacy carriers’ withdrawal and developed five additional focus cities: LA/Long Beach, Boston, Orlando, Fort Lauderdale FLL and San Juan. In particular, the decision to invest heavily in and significantly grow the Boston operation is paying off handsomely.

Fourth, JetBlue is better able to maximise revenues because of the flexibility offered by its “hybrid” business model, which can cater to a wide range of customers. As an extreme example, JetBlue goes after business traffic in Boston, while remaining “primarily a leisure player” in New York.

Those strategies have enabled JetBlue to outperform its peers in unit revenues and close the historical profit margin gap. In 2017 its 13% pretax margin slightly exceeded the 12.8% average margin achieved by its “peer set” (the top five US carriers plus Spirit). In Q1 2018 it had a one-point lead over the peer set average.

JetBlue’s improved financial performance has also reflected top executive changes. A sweeping management reorganisation in 2014, Robin Hayes’ appointment as CEO in early 2015 and Steve Priest’s promotion to CFO in early 2017 all represented a shift towards a greater focus on margins and ROIC.

But JetBlue has not bowed to pressure from the financial community to reduce its growth rate. It has continued to expand in Boston and Fort Lauderdale, because the management feels that strengthening relevance in the key focus cities is in shareholders’ best long-term interest. Since 2010 its system ASM growth has been in the 7-9% range in most years, far exceeding US industry average.

JetBlue’s continued growth can also be seen as an attempt to maintain relevancy in an increasingly consolidated market. JetBlue was outbid for Virgin America in early 2016, and the Alaska-VA merger subsequently knocked it down from fifth to sixth position in the US airline size ranks. And JetBlue’s chances of playing a role in any further US airline industry consolidation seem slim.

In the months that followed the ALK-VA announcement, JetBlue outlined plans to expand Mint to more transcon markets, ordered 30 more A321s with an option to convert to A321LRs, and began to talk about potential transatlantic service.

JetBlue’s balance sheet has been strong for a couple of years now, following successful deleveraging. In June total liquidity (including undrawn facilities) was 21.2% of LTM revenues and the adjusted debt-to-capital ratio was 31.3%. The strategy is to maintain investment grade financial metrics, have a leverage ratio of 30-40% and make opportunistic share repurchases.

But the downside of the growth and the fleet and focus city investments is that JetBlue continues to underperform the industry in terms of ROIC.

Also, despite all the growth, JetBlue has never managed to reduce its ex-fuel unit costs. It faces significant labour cost pressures but has not yet achieved any concrete results from the 2017-2020 “structural cost program” announced in December 2016.

For those reasons there is little excitement about JetBlue’s stock. The NYSE-listed shares have underperformed the Arca Airline Index in the past three years and are almost perpetually rated “market perform”.

All that was needed to cause a panic reaction in July was a modest setback in the margin recovery process and some cautious cost and revenue commentary. JetBlue reported an adjusted pretax margin of 8.2% for Q2 that was well below the peer set’s 12.4% margin, partly due to problems associated with a switchover to a new platform for ancillary activities. The market’s reaction was brutal: the share price plummeted by around 13% over two days (July 23-25) and has since recovered only partially.

What does a US airline do in this sort of situation? Hold an investor day, of course. JetBlue is planning one for October, at which it will discuss in detail the “many building blocks” that will help it attain its long-term goal of superior margins to its peers.

As another sign that the implementation of the strategic initiatives has moved into higher gear, in May JetBlue separated the roles of CEO and president/COO. Joanna Geraghty took over the management of day-to-day operations, freeing CEO Robin Hayes to devote his time to the long-term strategy and goals.

JetBlue has also announced some quick measures to try to boost profit margins, including slightly reducing its ASM growth rate in Q4, scaling down its Long Beach intra-west operations and moving some of that capacity to the transcon market.

Cost containment imperative

JetBlue needs to prove that it can deliver on its cost reduction targets. The 2017-2020 programme aims to achieve $250-300m of annual savings by 2020. The airline is also committed to maintaining ex-fuel CASM growth at 0-1% on a CAGR basis in 2018-2020.

But on July 27 JetBlue’s pilots ratified their first contract, which became effective on August 1. It was welcome news because it removed a major uncertainty hanging over the airline since the pilots unionised in 2014, but the “market competitive pay rates, per diems and 401k provisions” are estimated to add $110-130m incremental costs in year one alone. The deal included a $50m ratification bonus.

JetBlue immediately increased its Q3 2018 ex-fuel CASM guidance from 1-3% to 3-5%. It now expects unit costs to increase by 0.5-2% in 2018, instead of being flat. But JetBlue merely reaffirmed the 2017-2020 cost projections, implying that it will somehow “catch up” with the plan in 2019 or 2020.

Labour cost pressures look set to continue also because JetBlue’s flight attendants unionised in April and will soon be negotiating their first contract (though that will probably not impact the current cost cutting plan).

The three-year cost cutting plan does not include the impact of the E190/A220 fleet transition, which adds accelerated depreciation and transition costs through the mid-2020s. Those costs are estimated to be a 25bps headwind to the 0-1% plan projection.

JetBlue expects to achieve the structural cost savings in four areas: tech ops ($100-125m); corporate ($75-90m); airports ($55-65m); and distribution ($20m).

The best opportunities are with maintenance costs — an area where JetBlue has significantly underperformed. It has now invested in new technology and is negotiating new long-term “best-in-class” type maintenance contracts. At least two such agreements have already been signed (one for the heavy maintenance of the A320s and another for the maintenance of neo engines). There is currently an RFP out for the V2500 engine heavy maintenance.

In addition to renegotiating contracts with partners and suppliers, JetBlue recently completed a support centre organisational review that will lead to a streamlining of operations and an unspecified number of head office job cuts. The job cuts are culturally quite significant because they are rare (and possibly the first) at JetBlue.

The airport cost savings rely heavily on introducing more self-service technology to improve labour efficiency and the customer experience. The distribution cost savings, mostly completed, have come from renegotiation of contracts, termination of relationships with many third-party channels and encouraging direct bookings.

JetBlue’s unit costs will continue to benefit from upgauging the A320 fleet with larger A321s, and in 2019-2020 from the seat densification/cabin restyling project on the A320s. This will add 15, or 10%, extra seats, and the A320 fleet will be fitted with a cabin similar to the A321’s acclaimed cabin.

The A220 decision

JetBlue has benefited from operating a second, smaller aircraft type. The E190, introduced in 2005, has been critical for developing the Boston focus city, especially in shorter-haul business markets that require higher frequencies. But the E190 fleet faced higher maintenance costs and other investments to fly to a 25-year useful life.

So in April 2017 JetBlue initiated a 100-seat review that examined three options: keeping the existing E190 fleet; making changes to the Airbus fleet (presumably evaluating the A319); or moving to a new platform (the E195-E2 or the CSeries/A220).

The decision came in early July: JetBlue would transition from the E190 to the newly renamed A220. It placed an order for 60 A220-300s, with deliveries from 2020, plus 60 options (from 2025). There is flexibility to convert some of the options to the smaller A220-100. The aircraft will be powered by Pratt & Whitney engines and assembled in Mobile, Alabama.

The order was the first since Airbus completed its acquisition of a controlling stake in the CSeries programme from Bombardier on July 1, so JetBlue undoubtedly got a good deal. Moody’s estimated on July 13 that JetBlue may pay only $1.4-1.7bn for the 60 A220-300s, compared to their list price of $5.4bn.

JetBlue cited three main factors behind the A220’s selection: margin, flexibility (two versions) and a “fantastic range and network fit”. It had been a difficult decision, because the E195-E2 was “incredibly close from an economics standpoint”.

The Bombardier/Airbus union was described as a “secondary factor”, though it was useful in that it allowed JetBlue to reshape its existing Airbus orderbook. As part of the A220 deal, the airline converted orders for 21 A320neos into A321neos and adjusted the delivery schedule.

The 60 A220 firm orders will replace JetBlue’s 60 E190s between 2020 and 2025. The airline looks to sell the 30 owned E190s and will realise a $319m impairment charge in 2018. There will also be $90-110m of one-time costs this year associated with the return of the 30 leased E190s.

The A220 appears to be an outstanding aircraft in terms of operating economics, offering a higher seat count (130-160, compared to the E190’s 100), 40% lower fuel burn and 29% lower DOC per seat. The spacious cabins present a “real opportunity to redefine the interiors and continue to deliver the best product”.

JetBlue describes the E190-to-A220 transition as an “economic game changer”. According to its pro forma analysis based on full transition benefits in 2025, if JetBlue currently operated 60 A220s instead of 60 E190s, its 2018 system CASM would be 5.3% lower, EPS $0.65 higher and pretax margin and ROIC both about three points higher.

The A220 will add flexibility to JetBlue’s network strategy. While primarily targeted at the existing E190 markets — around a quarter of which would be better flown with larger-capacity aircraft today — the A220 is also likely to be deployed on the transcon.

The type’s range (up to 3,300nm) comfortably covers all of North America, as well as northern parts of South America and even Ireland/UK from Boston. But JetBlue is not looking to deploy the A220 on the transatlantic.

Nor will JetBlue deploy the type in long-haul secondary point-to-point markets. Pointing out that JetBlue is a focus-city based airline, its executives stressed: “We are not looking to do Frontier Airlines, do point-to-point flying. That’s not our strategy.”

In that regard JetBlue’s strategy differs from the one envisaged by its founder/ex-CEO David Neeleman’s planned US start-up, which signed an MoU for 60 A220-300s a week after JetBlue’s order, for delivery from 2021. Neeleman’s venture plans to focus mainly on point-to-point operations between secondary cities.

JetBlue is likely to purchase the A220s, funding them with debt and cash. The near-term capex impact of the A220 order and the A320neo-to-A321neo swap is modest, increasing annual spending only by about $100m, to total $1-1.2bn in 2018 and an average of $1.2bn annually in 2017-2020.

The A321LR and Europe?

JetBlue spent much time at its December 2016 investor day discussing the A321LR and its potential deployment to European destinations such as London, Paris and Dublin. The airline has flexibility to convert some of its A321 orders to the long-range version, but it has to give Airbus two years’ notice.

But that investor day enthusiasm soon fizzled out. JetBlue put Europe on hold, as it felt more pressure to improve margins and the domestic market offered more profitable growth opportunities.

JetBlue executives stated in July that any US-Europe routes would need to show equally strong returns to domestic A321 routes. The bar is high because the two domestic A321 versions (“all-core” and Mint) represent the highest-margin fleet types in the system.

However, route-specific returns are not the only criteria; there are also network considerations. JetBlue executives say that some of the European destinations are the biggest cities that the airline does not serve from Boston and New York. “We don’t have a Europe strategy, we have a Boston/New York strategy”, noted one JetBlue executive recently. “So any decision to go to Europe is really tied to our current focus city strategy.”

Europe will come — it is just not clear when. JetBlue executives said in July that they continued to analyse it and talk to Airbus, having just ordered another batch of undesignated A321neos. Should all of them be all-core and Mint, as previously, or could some of them be LR?

JetBlue may also have to decide between LR and XLR. The A321LR is due to enter service this year and has much commonality with JetBlue’s standard A321s, but it lacks the range to serve all of Western Europe. Airbus is now considering offering an even longer-range version, dubbed the A321XLR, but it may have less commonality with JetBlue’s A321s.

Focus city strengthening

JetBlue continues to target “mid-to-high single digit” annual ASM growth. This year’s growth will be 6.5-7.5%. The airline justifies the continued brisk growth on the basis that it is highly focused and accretive to earnings.

In the past couple of years virtually all the growth has been in Boston and FLL, where JetBlue feels it is relatively underrepresented with 30% and 25% market shares, respectively. Both focus cities have seen RASM strength. JetBlue is in the process of building Boston towards its goal of 200 daily flights and FLL to 140 daily flights. The main risks are Delta’s aggressive expansion in Boston and several LCCs’ growth in Florida.

The New York market remains “exceptionally strong” and continues to see growth via upgauging with all-core A321s (as do Boston and FLL).

The Latin America/Caribbean region, which accounts for nearly 30% of JetBlue’s capacity, has been a huge success story for the airline. But it is also prone to natural disasters. JetBlue was hit hard by last year’s devastating hurricane season. Puerto Rico took almost a year to recover to pre-hurricane capacity levels. But there continue to be opportunities: JetBlue is adding a new Boston-Havana route this autumn, consolidating its position as the leading US airline to Cuba.

The Latin America network will receive a major boost in October when JetBlue adds service to Mexico City from both JFK and Boston. The new routes will complement the airline’s existing MEX service from FLL and Orlando.

JetBlue is contracting at Long Beach because of the tough yield environment in the west, its relatively weak position in the intra-west market and because its request for customs/immigration facilities to allow international service at Long Beach was turned down.

Instead, JetBlue will continue building its margin-accretive transcon flying, which is performing well in both Mint and non-Mint markets (something the airline attributes to its “leading onboard experience” and “fewer competitive choices” since the ALK-VA merger). September will see two new transcon routes: JFK-Ontario (LA Basin) and Boston-Burbank.

New revenue strategies

JetBlue has delivered on the revenue strategies it originally laid out at the 2014 investor day, which has resulted in strong RASM performance.

Mint was recently named “best business class in North America” by TripAdvisor. It offers the key luxuries to match the legacies’ first class products (including lie-flat seats) but in a lower-cost way that meets the needs of a “modern traveller”.

One JetBlue executive said recently that he thought the pricing strategy was the key to Mint’s success. “We still have a fare in the mid-three digits at the bottom end. We think we can play all elements of the price spectrum.” He continued: “JetBlue has a strong core of high-end leisure customers and they can more easily access our everyday low pricing strategy than the legacies’ traditional way of pricing — higher fares or upgrades”. Mint has a 100% paid load factor; there are no free upgrades.

Originally meant to help JetBlue in only a couple of key business markets such as JFK-LA and JFK-SFO, Mint was such a hit that it was quickly expanded to Boston and some Caribbean markets, followed by Fort Lauderdale, Las Vegas, San Diego, Palm Springs and Seattle. This autumn will see the first Mint routes to Latin America: JFK-Costa Rica and Boston-St. Lucia.

The 34 or so Mint A321s in the fleet now fly roughly 20% of JetBlue’s ASMs. After the two new Latin America routes, Mint will be available on 23 routes linking 15 cities. Many of the Mint routes consistently outperform JetBlue’s system RASM and are among its most profitable markets.

The Fare Options platform, launched in 2015, has also continued to exceed expectations, driving an estimated $300m in incremental revenues in 2017. Customers can select a fare based on what they value (checked bags, reduced change fees, etc.) — an alternative approach to static fees. JetBlue has made multiple refinements to the bundling and pricing, which has helped drive “extraordinary growth” in ancillary revenue per passenger (now around $30).

This year JetBlue has turned its attention to non-air ancillary revenues. It has formed a new subsidiary, JetBlue Travel Products, to take over its vacations, car rentals and other travel-related activities and expand them in a “capital-light” way. The airline talked about “laying the foundation for the next level of ancillary earnings growth”.

Travel Products is based at FLL, “right at the centre of the travel and tourism industry”. JetBlue’s leadership also wanted to separate the unit geographically from the New York headquarters to give it a little extra independence. “Just as our venture capital arm JetBlue Technology Ventures has found success by being based in Silicon Valley, Fort Lauderdale will be the perfect location to grow JetBlue Travel Products.”

JetBlue has a history of being a technological innovator. An early example was LiveTV, which the airline developed over a decade and in 2014 sold to Thales for $400m proceeds. More recently, among other things, JetBlue has pioneered the use of biometrics and facial recognition technology in the boarding process.

JetBlue Technology Ventures was formed in 2016 to “incubate, invest in and partner with early stage startups at the intersection of technology and travel”. In just two years the unit has assembled an impressive portfolio of startups, of which at least two are already helping JetBlue: Gladly (a multi-channel customer service tool) and ClimaCell (provides more accurate local weather forecasts).

This year JetBlue began a first-of-its-kind codeshare partnership with JetSuiteX, which operates short-haul public charter flights, sold by the seat, between private terminals at major West Coast destinations with 30-seat E135s. The idea is to offer the speed and comfort of private jet travel at affordable prices. JetBlue places its code on JetSuiteX flights, but not vice versa, and the two airlines’ flights do not connect.

Launched in April 2016, JetSuiteX is a sister company of JetSuite, one of the largest private jet operators in the US. In October 2016 JetBlue acquired a minority equity stake in the company and gained a board seat. In April 2018 JetBlue increased its stake and Qatar Airways also became a minority investor. The purpose was to fund JetSuiteX’s growth; an order for 100 12-seat hybrid-to-electric aircraft from Zunum Aero (another JetBlue-backed venture) followed, for delivery from 2022.

Though currently very small, JetSuiteX offers JetBlue customers new options on the West Coast and fits in well with JetBlue’s efforts to build higher margins into the west. CEO Robin Hayes is enthusiastic: “A great product with a competitive fare — we think it’s a market with a lot of growth potential, and we clearly want to be part of that.”

| At 11 July 2018 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Operating Fleet | Firm Orders | Delivery Schedule | |

| A320-200 | 130 | ||

| A321-200 | 57 | 6 | 2H 2018 |

| A321neo† | 85 | 2019-2024 | |

| E190 | 60 | ||

| A220-300‡ | 60 | 2020-2025 | |

| Total | 247 | 151 | |

Notes: † option to substitute some of the A321neo orders with the A321LR. ‡ plus 60 options (from 2025), some of which can be converted to the smaller A220-100.

Source: Company reports

| Pre-11 July 2018 | Post-11 July | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Delivery Year | E190 | A320neo | A321† | Total | A220 | A321† | Total |

| 2018 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | |||

| 2019 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 | |||

| 2020 | 10 | 6 | 7 | 23 | 5 | 15 | 20 |

| 2021 | 7 | 16 | 4 | 27 | 4 | 16 | 20 |

| 2022 | 7 | 3 | 17 | 27 | 8 | 15 | 23 |

| 2023 | 14 | 14 | 19 | 14 | 33 | ||

| 2024 | 5 | 5 | 22 | 12 | 34 | ||

| 2025 | 2 | 2 | |||||

| Total | 24 | 25 | 66 | 115 | 60 | 91 | 151 |

Note: †2018 deliveries all ceos; from 2019 all neos.

Source: JetBlue

Source: Company reports