European consolidation: another one bites the dust

Jul/Aug 2017

It always amazes how long a loss making airline can survive before it goes bust. Air Berlin has been struggling as a going concern since it came to the markets with its IPO and dubious “hybrid” operating strategy in 2006. In the past ten years it has lost a total of €2.4bn at the operating level (a negative margin of 6%) and €2.7bn at the net. In the past few years it has been kept alive through constant cash support from major shareholder Etihad who took a 29% stake in 2011. Now, that shareholder has pulled the plug, and Air Berlin has filed for bankruptcy protection, gaining a €150m emergency cash loan from the Federal German Government to keep operations running to the end of the Summer season pending sale and reconstruction of its parts.

There is not much value in the company. The aircraft fleet is almost all leased. The net equity on the balance sheet at the end of March stood at a negative €(2.1)bn excluding a now unrealistic credit to Etihad for its “hybrid equity” funding of €358m. What had been promulgated as a rescue package, the divestment of the charter and tourist oriented business to a new “bad Air Berlin” structure involving TUI, Austrian subsidiary Niki and Etihad (see Aviation Strategy October 2016) has fallen apart, so the NAV represented at that time may represent a significant overstatement of the asset position.

Given that Etihad has washed its hands from its investment and reneged on a promise to keep the company afloat for at least 18 months, it may be that it will just write off its €358m perpetual convertible, a €350m loan granted in April this year repayable in 2021, its €100m investment in a new convertible loan issued in January and maturing in 2019; Abu Dhabi could also just write off its banks’ €245m loans recently extended to April 2019. If so the company would still have a negative equity of €(1.4)bn.

The Air Berlin operation does have some assets. It holds some 30% of the slots at the heavily constrained Düsseldorf airport and 42% of the slots at Berlin Tegel. Whether these holdings can be monetised is debatable:

-

Firstly Air Berlin has wet-leased 40 aircraft to Lufthansa/Eurowings (as part of the split between the “good” and “bad”) and it is usually the case that the published operator will have possession of the slots.

-

Secondly, the only active trading markets in slots in Europe involve either London Gatwick or London Heathrow; and at these airports, from our experience in slot valuations, it is only long haul carriers who are willing to pay for access.

-

Thirdly, when and if Berlin Brandenburg finally opens, Tegel is scheduled to close, giving a finite time to the net present cash flow a slot purchase may represent.

-

And fourthly, should Air Berlin fail unsold, those slots will in any case become available to new entrants.

Having said this, Air Berlin has four distinct and disparate business segments which could appeal to some optimistic buyer:

- The traditional sun, sea, sex and sand seasonal operations from Germany and Austria to what the Germans always refer to as “touristik” destinations. This is what they tried to offload to a new charter operation to be set up by TUI and Etihad as mentioned above.

- A significant domestic operation (the legacy of its acquisition of dba) in competition with Lufthansa and its subsidiaries.

- A European point-to-point network from German cities.

- A long haul A330 operation from Düsseldorf — the result of its acquisition of LTU.

The question is what if anything would a potential purchaser be buying? There may be some value in the Niki brand — the Austrian leisure operation — and in Austria Niki Lauda’s legacy may retain some local kudos. The Air Berlin brand however is tainted by the decade of losses.

However, it appears from press comments that Air Berlin is in talks with a handful of players — including perhaps Lufthansa, Condor, TUI and easyJet — vying to take on Air Berlin’s fleet, pilots and cabin crew.

The government has put its oar in and has suggested that the only solution is a break up, helpfully waking up to the fact that “the Air Berlin model has failed”, with some politicians suggesting that a large portion of the operation should go to Lufthansa to “foster a national aviation champion” (as if they didn’t have one already).

At the same time the transport minister Alexander Dobrindt dismissed competition concerns saying “there is no transfer of Air Berlin as a whole to Lufthansa, there are parts of the business that will go to Lufthansa and there are interested parties for other bits of the business so we do not expect cartel difficulties”.

Meanwhile, aviation veteran Hans Rudolf Wöhrl — the architect behind the sale of dba and LTU to Air Berlin in the first place — has entered the fray suggesting that he would consider acquiring the whole business if only someone would let him look at the books. This comment has been mirrored by Ryanair’s Michael O’Leary who also stated that the bankruptcy process was a “stitch up” to help strengthen Lufthansa, indicating perhaps that Ryanair would only be interested in Air Berlin if it were allowed to acquire the entirety of the bankrupt carrier and not just what might be left after Lufthansa has taken its pick of the assets.

Failure brings opportunities

Air Berlin will disappear and its demise will change the German market, and possibly in a dramatic way. For the past decade it has seemed that Lufthansa has been happy to co-exist in the domestic market with a financially weak competitor, to curtail the incursion of easyJet and Ryanair.

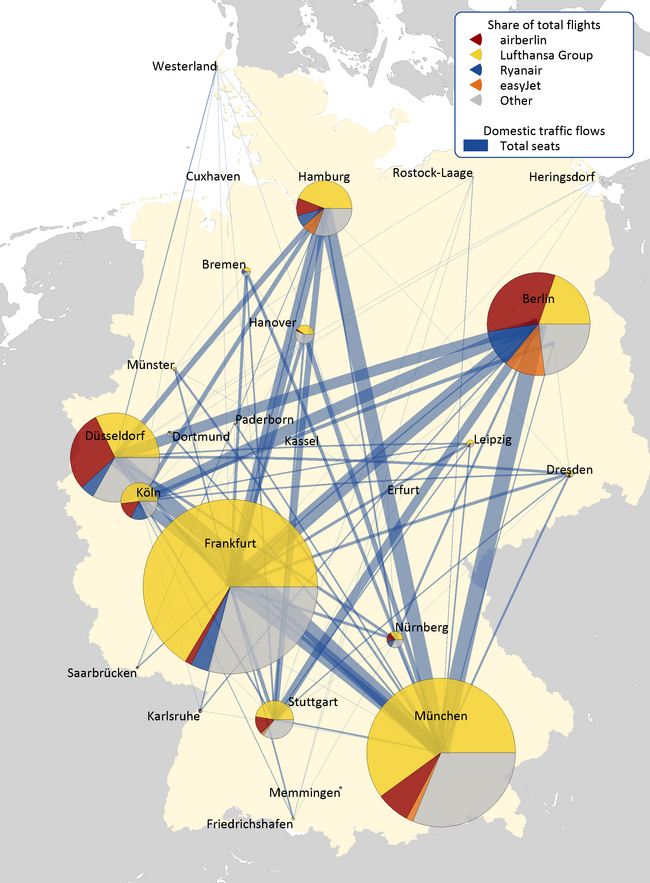

And the domestic market is pretty vibrant, reflecting the country’s federal nature and historically independent states. Unlike some other European countries Germany is relatively decentralised and there are significant flows of domestic air traffic between industrial centres and state capitals (see map), with the federal capital distanced from the financial centre (Lufthansa’s hub in Frankfurt), the industrial Nord-Rhein Westfalia (the most populous state in the Federation), Hanseatic Hamburg, and Bavaria.

Furthermore nine of the top 12 city-pairs by annual seat capacity on routes involving Germany are domestic (see chart).

Lufthansa as a group has a 71% share of all domestic German capacity (see chart). Three quarters of this is essential to its network business — providing feed to its two hubs at Frankfurt and Munich. The other quarter is perhaps maintained to continue to provide its corporate contracts with services as an encouragement to use its long haul services. With its high cost base, it has struggled to make profits; and the transfer of these routes to its lower cost subsidiary germanwings has been a focus of its strategy in the past few years. Air Berlin has been the next largest operator with 26% of capacity. Even Transport Minister Dobrindt might accept that should Lufthansa take on Air Berlin’s domestic services it would be a somewhat anticompetitive move.

Why haven’t Ryanair and easyJet made greater inroads into the German market? One of the main reasons must be that it has been easier to develop services elsewhere in Europe.

Having said that, Ryanair has an 8% share of capacity out of Germany, and easyJet 3% — albeit less than half their respective market shares in Europe as a whole. Both have a strong presence at Berlin Schönefeld, but of the two only Ryanair operates domestic services. It made a major push into Cologne/Bonn and Frankfurt this year and has ended up with a 20% share of capacity on Cologne to Berlin route, a noticeable presence in Frankfurt and 2% share of domestic capacity.

Whatever the Air Berlin bankruptcy solution, the competitive landscape in Germany is likely to change dramatically. Could it be that the German domestic market could mirror the development in the UK — with the LCCs dominating the non-hub routes? Is this an incentive for the LCCs to adjust their product to make it more attractive to the conservative German consumer and, more importantly, change the local market perception of LCCs?

| Total | 10 | 37 | 6 | 15 | 1 | 13 | 82 |

| airberlin | Niki | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 737 | A320 | A321 | A330 | A320 | A321 | Total | |

| GECAS | 11 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 15 | ||

| AerCap | 3 | 1 | 9 | 13 | |||

| BOC Aviation | 3 | 3 | 6 | ||||

| Avolon | 3 | 1 | 1 | 5 | |||

| BBAM | 2 | 1 | 2 | 5 | |||

| ICBC | 3 | 1 | 4 | ||||

| ALC | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | |||

| BoCom Leasing | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||

| AWAS | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||

| Castlelake | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||

| CDB Leasing | 2 | 2 | |||||

| Deucalion | 2 | 2 | |||||

| Hannover Leasing | 2 | 2 | |||||

| ORIX | 2 | 2 | |||||

| 16 other lessors | 4 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 16 | |

Note: excludes aircraft on wet-lease to Eurowings

Note: Seats arriving and departing German airports 2017. Domestic routes in blue