Ouigo: SCNF adapts LCC model to TGV

Jul/Aug 2014

Imagine a new low-cost airline based in the outskirts of Paris with a fleet of 480 Airbus A380s adapted to carry up to 1,000 passengers. Fares for a third of seats on its short-haul flights would be as low as €25. Well, if you are in France or on its borders that is what is coming soon to a station near you.

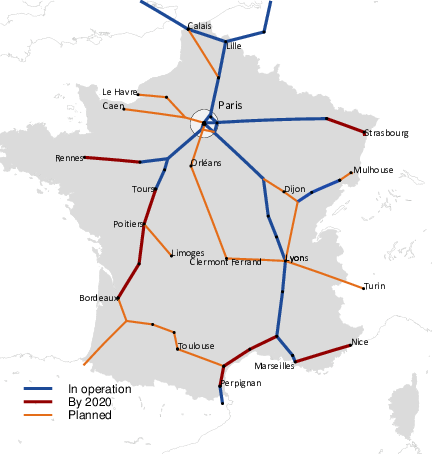

French railways, SNCF (Société Nationale des Chemins de fer Français), have a problem with their hitherto successful high-speed trains, TGV (Train à Grande Vitesse). Revenues are falling and operating costs are rising. One answer is to turn them into low-cost high speed trains, modelled explicitly on easyJet or Ryanair. An initial service started last year to the south of France from a station on the eastern outskirts of Paris. Now SNCF is considering rolling out its Ouigo budget service across the whole high-speed network, leaving only 20% of the operations with a full service TGV.

This the same SNCF whose TGVs obliterated Air France’s domestic network when it started running the first high-speed trains between Paris and Lyons in 1981, capturing nearly 90% of the traffic by the end of that decade. It is the same state rail monopoly whose sleek 200mph trains have been imitated all over the world — the very embodiment of French chic, style and savoir-faire.

But the fact is: TGV trains hide SNCF’s embarrassment. Much of the French rail network is in serious trouble. In the past couple of years it has even started to have the sort of accidents that so tarnished the railway in the UK in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Starting with the Paris region, whole swathes of the rail network are crumbling. Ancient, dirty trains rumble along crumbling tracks with their speed limited to minimise further damage. France spends about as much as other European countries subsidising its railways. But, whereas in, for example, Switzerland, the money goes to keeping the whole network in fine fettle, in France half of it goes to keeping fares low, notably for suburban or regional services. SNCF is paid by regional transport authorities for providing train services judged to be socially and economically useful.

In addition, the state-owned Réseau Ferré de France which owns and operates the tracks uses high tolls on the TGV lines to help pay for the upkeep of the rest of the network, and these are set to increase steeply. Track tolls, which have risen by a third since 2007, now account for 40% of the average TGV rail ticket. This, combined with falling passenger numbers in the past three years as the great recession has hit France hard, has damaged the finances of SNCF Voyages, the subsidiary that runs the TGV services.

The results for the first half of this year, published at the end of July, saw TGV revenues fall by 3%, continuing a trend of the past three years. Profits tumbled from €389m to €259m and the operating margin slipped again from 11.4% to 8.1%. As recently as 2011 the profit margin was over 14%. The operating margin will erode further as the impact of higher tolls filters through, to levels completely inadequate to service compatible required capital investment and the existing debt burden of about $44billion.

This is the challenge facing Guillaume Pépy, chairman and chief executive of SNCF.

French government finances are in such dire straits as to rule out any possibility of greater state subsidy. Indeed the government counts on receiving dividends from the railway. The French public would take to the streets to oppose any rise in fares to the level that their phlegmatic British neighbours tolerate so placidly.

One option is to cut back the TGV network, with its 180 origin-destination routes, to concentrate on its profitable core of some 40 routes. Scores of French towns would lose their direct TGV service to Paris. Instead passengers would have to take slow trains using a network of regional hubs, some connected to TGVs. The number of TGVs would be halved to around 240 and the latest LGV (Ligne a Grande Vitesse) — only one third built so far — would simply be abandoned. This option would go down badly with politicians so it is probably only being discussed to scare the powerful trade unions into accepting drastic changes. (There was a damaging ten-day strike earlier this year.)

The second option would be to go all out for growth, cutting fares across the board to raise passenger loads and increase train usage from barely six hours a day to around 15 — the same utilisation that LCCs aim for. The trouble with this policy is that, with parallel labour efficiency improvements, it would leave the TGV business with an annual loss of around €400m according to an internal study at SNCF.

The third option is the most likely to be adopted. This consists of changing working methods and timetables to get 15 hours a day out of each train, with a root-and-branch approach to improving labour productivity, cutting costs and implementing an LCC-type operating model.

The Ouigo trains are to have 20% more seats crammed into their double decks, with comfort levels reminiscent of Ryanair. There is no buffet car. Passengers have to buy tickets online and turn up 30 minutes before departure to facilitate boarding. There are no ticket offices or uniformed staff hanging around stations doing nothing, as only railway people do. Only hand baggage is allowed free; anything else is charged separately. The team of four onboard staff have to go through each carriage at the terminus to pick up the rubbish and tidy the seats, just like on a budget airline. Children travel for a low fare regardless of destination.

The vision for SNCF in 2020 is becoming clearer, though there is likely to be blood on the tracks before it is achieved. As for easyJet, France's second largest airline, and the other LCCs (and the network carriers) a new dynamic is entering short-haul competition.