UAL and AMR: United's merger challenges, American's merger explorations

Jul/Aug 2012

Somewhat ironically, in recent months United Continental Holdings (UAL) – the result of the October 2010 merger between United and Continental — has been experiencing terrible merger integration problems just as American, which has been in Chapter 11 since November 2011, is effectively being forced into considering a merger with US Airways.

Of course, these developments are totally unrelated. But UAL’s problems serve as a reminder that airline mergers are risky affairs. They are extremely difficult to execute, involve considerable pain, offer only long-term benefits and should only be considered if the potential rewards are substantial (as they probably are in UAL’s case).

Many of the issues that UAL has been experiencing this year resulted from an over-ambitious IT/reservations systems switchover in early March. UAL has been plagued by computer glitches, soaring customer complaints, poor operational performance, weak RASM growth, rising CASM, deteriorating profit margins and labour strife so extreme that the pilots voted on July 17 in favour of a strike (a symbolic gesture since the federal mediators had not released them from contract talks) .

Industry observers have been alarmed that UAL is having such difficulty integrating the two subsidiaries. JP Morgan analyst Jamie Baker wrote in a July 26 research note that some investors were so concerned that they had asked: “Is there a possibility that UAL will emerge as this decade’s AMR?”

The investors are not worried about a liquidity crisis or another bankruptcy; rather, they fear that United could be on a path of gradual decline and would eventually emerge as an “industry laggard” similar to what AMR was in the last decade. JP Morgan analysts said that they did not expect that to happen, but they called for a “more aggressive management stance” at UAL to help restore operational performance and profit margins.

The key questions for United now are: Can it quickly fix the operational and service issues, and at what cost? Will its unit costs soar as a result of the pilot deal, which was facilitated by Delta’s recent industry-leading contract?

At American, the pilots’ overwhelming rejection of the company’s “last, best and final” contract offer on August 8 dashed the management’s hopes of reaching consensual labour agreements and completing the Chapter 11 restructuring by year-end. The resulting labour strife and delays make an eventual merger with US Airways even more likely than before.

UAL’s integration challenges

In contrast with Delta and Northwest, which integrated their computer systems in stages (with relatively smooth results), United and Continental decided to do it all at once. The idea behind the “big bang” systems cutover was to limit the hassle to customers to the shortest possible period.

UAL executives have called it “the single largest technology migration in the history of aviation”. CEO Jeff Smisek explained recently that the carrier “added new stress to the system by simultaneously converting to a single passenger service system, implementing hundreds of new processes and procedures, rerouting aircraft across our network, and harmonising our maintenance programmes”.

It was a critical integration milestone that was supposed to drive significant merger synergies in 2012. Instead, the outcome was so messy that United has only incurred additional costs. Many of the issues lingered on for months and some have still not been resolved.

In May UAL came worst of 15 major carriers in all four key service metrics – on-time performance, cancellation rate, misplaced bags and consumer complaints – in the DoT’s monthly rankings.

United’s unit revenue growth has also continued to trail that of the industry. According to BofA Merrill Lynch analyst Glenn Engel, UAL’s 2.9% PRASM growth in the second quarter was 3.5 points below the major carriers’ average increase. The gap was similar to that seen in the first quarter. In addition to the integration issues, the RASM underperformance reflects United’s relatively heavy exposure to the large-corporation segment, which has begun to show some weakness due to the global economic slowdown.

Revenue synergies from the merger were supposed to boost United’s RASM performance this year. Instead, United is now expected to be the only one of the top seven US carriers to see unit revenues decline in the current quarter. It is also expected to have the industry’s smallest RASM increase in the fourth quarter.

The fiercest battles between the top three US airlines are for corporate customers and elite-status FFP members. Reports suggest that Delta has definitely gained market share of those segments. United has won some market share from AMR because of the latter’s bankruptcy, but AMR recently claimed that it had captured frequent flyers from United because of the merger integration issues. That said, UAL continues to win new corporate accounts thanks to the larger combined network and the extra sales efforts mounted since the merger; its executives said that revenue from corporate accounts rose by 16% in the second quarter.

Smisek said in UAL’s second-quarter call on July 26 that the airline was intensely focused on restoring its operational integrity “in fairly short order”. The “aggressive effort” under way includes increasing airport and maintenance staffing levels and adding back the spare aircraft that were removed earlier as part of the maintenance systems harmonisation.

But fixing the woes is adding to the cost pressures UAL is feeling this year. In addition to the substantial one-time integration charges, unit costs will increase as labour contracts are harmonised and capacity declines modestly. UAL’s ASMs are slated to decline by up to 1.5% in 2012, and non-fuel CASM is expected to rise by 2.5-3.5%.

UAL reported ex-item operating and net profits of $781m and $545m, respectively, for the second quarter, down 15.3% and 20.3% on the year-earlier period. Revenues rose by 2.4%. Net special charges amounted to $206m, including $137m of integration items and $76m costs associated with a voluntary employee severance programme.

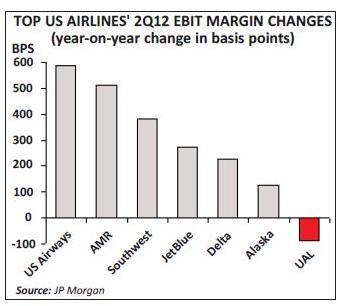

The operating and ex-item net margins were a respectable 7.9% and 5.5%, respectively. But analysts pointed out that UAL was the only major US airline whose profit margins declined in the latest period.

While UAL is expected to remain profitable (like its peers, it is enjoying an unprecedented multi-year profit run), the merger-related problems mean that it is likely to be the only carrier to see earnings dip in 2012. In 2013, however, analysts cautiously hope that UAL will outperform the rest of the gang.

UAL had an ample $8.2bn in unrestricted liquidity, or 22% of last year’s revenues, at the end of June, giving it flexibility as it integrates and manages its debt maturities. Its ROIC exceeded 10% on a trailing 12-month basis.

The proposed joint pilot contract at United includes agreement on all the major economic issues. When finalised, the deal will be subject to approval by the governing boards of the two pilot groups and ratification by members. The next step would be talks on seniority list integration – a contentious subject, but UAL’s two pilot groups have agreed to submit the matter to binding arbitration if they cannot agree on a list. The pilot negotiators estimated that the contract could be in place by the end of this year and a single seniority list by next spring. Getting these deals done is crucial, because UAL will then be able to freely allocate crews and aircraft across the network – important for achieving the full synergies.

Both sides have made it clear that the industry-leading contract that Delta’s pilots ratified in late June paved the way for the deal at United, which provides improvements in pay, work rules, job protection and benefits, to compensate for the concessions that both pilot groups made in the last decade. One union leader was quoted saying that the deal was “on par with Delta from a pay-rate perspective”.

The Wall Street Journal reported that CEO Smisek himself acknowledged in a memo to pilots in May that the Delta agreement “raises the market pay for commercial airline pilots and effectively sets a new competitive standard for pilot pay”. He pledged that United would be responsive to the Delta terms and needed to “adjust our current contract proposal to be competitive”.

United recently gave Aer Lingus 90 days’ notice to terminate their longstanding codeshare agreement on the Washington-Madrid route, which is operated by Aer Lingus. That “outsourcing” had been a particular bone of contention with the pilots.

It does sound like a potentially very expensive pilot deal. But, in return for industry-leading pay, UAL could secure important concessions, such as a significant relaxation in the pilots’ scope clause that would allow more large regional jets to be operated by commuter affiliates.

The Boeing narrowbody order demonstrated that, unlike American, United sees benefits in ordering from just one manufacturer. The July order included 100 737 MAX9s (plus 100 options), for delivery from 2018, and 50 737-900ERs (plus 60 options), from late 2013. United’s 270-plus firm orders also include 50 787s and 25 A350XWBs. The 787 is expected to begin commercial service in October (following delivery in September), initially between UAL’s US hubs, then on Houston-Lagos and in 2013 to launch Denver-Tokyo.

AMR’s growing merger certainty

AMR’s management wants to restructure independently and earlier made it clear that it would consider consolidation only after emerging from Chapter 11. However, the airline’s standalone business plan has been widely criticised as weak and uninspiring. US Airways took advantage of that and succeeded in winning the support of AMR’s very unhappy workforce for a possible future AMR-US Airways merger. In an unprecedented move, US Airways in April announced tentative agreements with American’s three key unions that would give them better terms than what AMR is offering in the event of a merger taking place (see Aviation Strategy, April 2012).

In May key creditors and bondholders put pressure on AMR to consider alternatives to the standalone business plan. AMR signed a “protocol” with its nine-member unsecured creditors’ committee (UCC) to explore strategic options, including a possible sale. Those options would be considered side-by-side with the standalone plan.

In July AMR’s CEO Tom Horton presented plans to reach out to at least five potential merger partners (Alaska, Frontier, Virgin America, US Airways and JetBlue). This “search” officially kicked off on July 27 when AMR sent out confidentiality agreements. But the problem is that only US Airways seems to be interested (and many of the others are also too niche).

AMR has indicated that it would also consider offers from private equity firms, other US legacies and even foreign carriers. Delta is believed to be considering a bid, though many regard it as unlikely because it would probably not pass regulatory muster. IAG is reportedly considering buying a small stake to protect the alliance, if invited to do so by its partner.

In the meantime, US Airways’ CEO Doug Parker has continued to publicise the merits of an AMR-US Airways union. US Airways cannot yet bid for AMR, because AMR currently has exclusive rights until December 28 to propose a reorganisation plan. However, US Airways could take a merger bid directly to the UCC, and the UCC could at any point seek to have the court revoke AMR’s exclusive rights.

AMR’s management has strived to complete the Chapter 11 restructuring quickly, so that it could present the standalone plan during the exclusivity period. It has made good progress with debt, lease and facilities restructuring. Also, AMR has outperformed the industry in terms of RASM in recent months, amid signs that the “cornerstone” and alliance/JV strategies are at last producing dividends. AMR even achieved a small $95m ex-item net profit in the second quarter – its first positive result in that period since 1997.

On the labour front, AMR also seemed to be on the home stretch in terms of securing consensual agreements adding up to around $1bn of annual cost savings (negotiated down from the original $1.25bn). By early August all seven TWU unions had ratified their agreements. The flight attendants conclude their voting on August 19.

But the pilot vote ruined the management’s plans. The rank-and-file rejected the contract with a 61% majority, even though the terms represented a significant improvement over the original proposals (including, among other things, modest pay increases, elimination of furloughs and a 13.5% equity stake in the company).

All of the unions still strongly support a potential US Airways bid. But the union leaderships had urged members to approve AMR’s final offers as an “insurance policy”, to avoid harsher court-imposed terms and because it was seen by many as the shortest path to a merger with US Airways. The thinking was that the sooner AMR gets the restructuring done, the sooner a plan from US Airways can be considered.

The pilot vote reflected the deep anger and frustration with the management that had simmered since AMR’s workers granted $1.6bn of voluntary concessions in 2003, the six-year length of the contract and other factors. Many pilots felt that approving the deal would be akin to endorsing the management. The vote led to an immediate resignation of the APA president at the request of the union’s board.

The court was expected to approve AMR’s request to reject the pilots’ existing contract on August 15, but it is not certain that AMR will impose the sort of “draconian” terms that some people have suggested. The main thing is that the two sides need to resume negotiations on a long-term contract – without one AMR would not be allowed to exit Chapter 11.

Analysts have predicted that the main impact of the pilot vote is to delay everything – the filing of AMR’s restructuring plan, consideration of a possible US Airways bid and exiting Chapter 11. However, the delay may work in US Airways’ favour. This is because, as one analyst suggested, the pilots have little to lose and could drag out the contract negotiations. A mutually agreed deal may not be possible. A bid by US Airways could win strong creditor support if it facilitated a pilot contract and more stable labour relations at AMR.

One of the many odd aspects of US Airways’ involvement here – and something that requires further clarification – is that US Airways still operates with two separate pilot groups following the 2005 merger with America West. How could US Airways bring labour peace to AMR if it cannot integrate its own workforce? But there is the intriguing possibility that an AMR-US Airways deal on the table might help break the deadlock in US Airways’ own union negotiations.