Legacy subsidiaries: Quest for a successful model

Jul/Aug 2012

Legacy carriers have all tried to react to the competitive threats of lower cost new entrant competitors by creating their own lower cost subsidiaries. Over time, as the LCC phenomenon has spread round the world, this reaction has developed in various ways; but rarely successfully.

In the US the network majors tried to establish in-house LCC subsidiaries — some of them several times. They all failed. It may have been that the attempts to establish the likes of Song (Delta) or Ted (United) were just attempts at union-bashing, ill-fated attempts to reduce costs fast enough to compete in some way with low fares of the point-to-point competition; an interim measure while putting off the opportunities available under Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection to reduce employee costs throughout the group operations.

In Europe the early reactions were also to join the LCC revolution with separately branded subsidiaries: British Airways’ Go being a brand new start-up; KLM’s buzz a spin-off from its regional British subsidiary Air UK. Neither of these were integrated into mainline operations. The logic, such as it was, was that these subsidiaries could close the operating cost gap on the new entrants but would also have a huge advantage in capital costs because of the halo effect of their parents – totally wrong, as it turned out.

BA disposed of Go in the fear that it had created an animal that would cannibalise its own core traffic; it was subsequently acquired by easyJet to give the Luton based carrier a leg up in development towards becoming one of Europe’s largest carriers. Buzz equally went to Ryanair for similar reasons. Both acquisitions were financially painful for the acquirers.

Lufthansa by contrast gradually acquired a majority stake in germanwings and was happy to treat it as an entirely separate brand within its portfolio of disparate airline products. It also allowed it to compete directly with its main Lufthansa brand, albeit on non-hub flying. Air France got into the game late, probably underestimating the incursion of easyJet into its home bases at CDG and Orly. It established Transavia France as a 'leisure based' carrier using the expertise of the KLM’s moderately successful transavia.com. Alitalia tried with Volare. SAS has been trying to make sense of Blue 1.

None of these in-house subsidiaries have been successful; primarily perhaps because the parent companies had no real interest in allowing them to grow outside their home country (and away from the limitations of national based unions) in the way that easyJet, Ryanair and Wizzair have been able to do; partly because of an overwhelming belief in their core brand dissuaded them from allowing the subsidiaries to grow too fast and cannibalise the core activities.

The LCC revolution took decades to cross the Atlantic, but as in the case of the development of many product ideas, only a few years to get to Asia. Now the focus is in the Far East; where the LCC business model and the reaction to it is developing in new ways. With ownership restrictions still in place, the start-up LCCs have (with collusion in various degrees of usefulness from nation states) been able to establish minority owned branded subsidiaries in other countries in the region to develop a regional brand awareness.

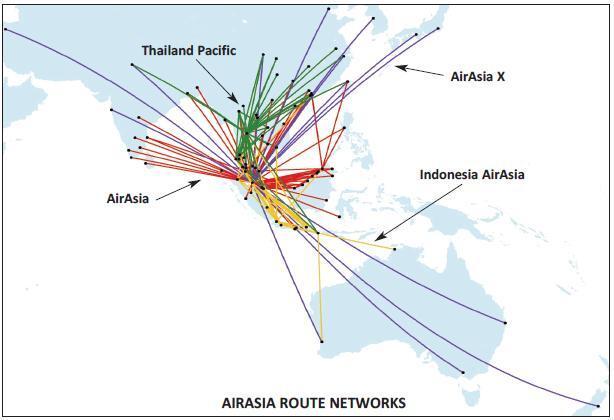

AirAsia, for example, based in Malaysia, has established subsidiaries in Thailand, Indonesia to allow it to create a Southeast Asian network. It plans to open AirAsia Japan in partnership with ANA in 2013. Distances within South East Asia between major centres are also far longer than comparative routes in the US or Europe; and AirAsia compounded the problem for the legacy carriers by establishing AirAsia X as a separate long-haul low cost model. In doing so it created as if almost by chance its own unbundled network model allowing self-transfer at the low cost terminal at Kuala Lumpur.

In Australia, Qantas appears to have created a new type of in-house low cost subsidiary; again one that could possibly be described as union-bashing. Following the demise of Ansett and near collapse of Air New Zealand, and the emergence of new low cost competition (Virgin Blue, now Virgin Australia), it seems to have caught its unions napping when it established Jetstar in 2004. The official story at the time may have been that this low cost fully owned subsidiary would only be used on 'leisure' routes — notably naturally low yielding routes into and out of the Northern Territories and Gold Coast, which were unsuited to Qantas' high cost structure.

The unions seem to have rationally accepted that it also made sense for Jetstar to operate longer haul leisure routes out of Japan, which again made little sense for Qantas. Virgin Blue also seems to have dismissed the development as one which as with similar moves in the US was bound to fail once the unions discovered what was going on.

However, Qantas has treated its low cost subsidiary as a fully fledged subsidiary, coordinated within the Qantas Group; and been willing to foster it as a fully integrated new brand. Qantas and Jetstar bid internally for resources on a route by route and flight by flight basis: the one proving the potential for the greatest group returns being allocated the opportunity to operate the flight. Importantly the two brands do not compete, but work together in complement. Distribution systems are linked: both carriers cross-sell each others' services. This can lead to both carriers operating the same route (they overlap on 32 routes overall) but the process is designed to ensure that inter-brand competition and demand cannibalisation is minimised while maximising group returns. Jetstar participates in the QF and partners' FFPs; and code share agreements with common partners.

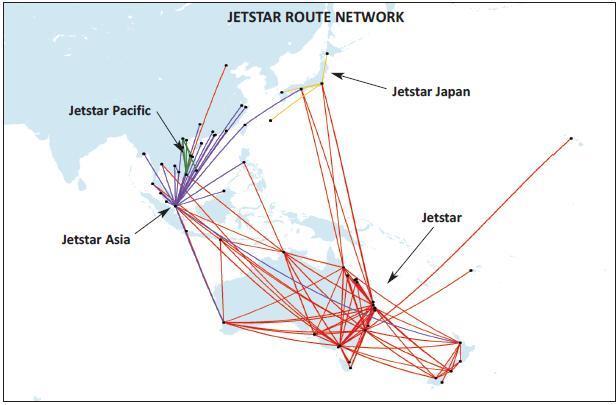

Jetstar too has been used to access cross-border brand development as such as AirAsia. It has built up 50% owned Jetstar Asia, based in Singapore — possibly allowing it to access slightly lower employment costs and more efficient crewing. It also has a 30% stake in Jetstar Pacific based in Vietnam — although it is currently limited to domestic services. It recently established Jetstar Japan in partnership with oneworld alliance partner JAL — initially designed to operate domestic routes (it started operations in June this year with three A320s and plans for a 21 strong fleet) it will undoubtedly go international before long. It has also announced plans to start Jetstar Hong Kong in a joint venture with China Eastern — the first LCC to be based in Chep Lap Kok — which, AOC permitting, is set to start operations next year.

Also, it has the domestic New Zealand operations and increasing involvement in trans-Tasman routes — all notoriously and historically difficult to operate efficiently. In all these Jetstar has the advantage of being able to access the Qantas Group fleet, order book, and financial resources; and it may perhaps be assumed that the parent group sees greater shareholder returns from allocating its capital to its new brand.

These moves have spurred a splurge of legacy carriers' responses in the region. SIA has set up Scoot (although it has operated its own single aisle leisure carrier Silk Air for many years). This is operating hand-me-down 777s and is designed to attack the “burgeoning market” for medium- to long-haul intra Asian low fares demand. JAL, as mentioned, has set up a joint venture with Jetstar. All Nippon is apparently creating two new LCCs — associate company Peach (which started operations in March 2012) in partnership with two other Japanese investment companies, and AirAsia Japan as a joint venture with AirAsia using the Malaysian company’s know how. Thai, being attacked on the one hand by AirAsia Thailand, and on the other thwarted by plans to develop a joint venture low fares in-house operator in conjunction with Tiger has set up its own short-haul LCC Thai Smile. Cathay notably has yet to offer any response.

Is the Jetstar model successful? In the first half of the group’s financial year ended June 2012 Jetstar achieved operating profits of AUD147m (US$146m) up by 3% on the year before, while Qantas mainline returned AUD66m, down by 60% on the year before level (although admittedly impacted by the effects of strike action of an estimated AUD194m). Jetstar produced a third of group capacity in the first half and carried 64% of the total number of passengers. Of course the published figures come under criticism — basically referring to transfer pricing in the group accounts — but on published figures it may appear that Jetstar’s unit operating cost of 4.1cents/ASK is at least 30% below that of its sister company — before accounting for stage length differences.

Qantas may have been lucky in establishing and developing Jetstar. It appears to have its unions unawares, and Virgin Blue strategically seems to have dismissed the competitive potential on the basis that the QF unions would eventually squash it. The recent unrest among the mainline carrier’s unions may not completely have gone away. Along with the austerity restructuring of QF long-haul mainline operations and the distrust of the published figures may suggest an exacerbation of weakened industrial relations.

Could Qantas' development of Jetstar successfully be replicated in Europe, Asia or elsewhere?

Lufthansa has an apparent need to maintain a reasonable level of non-hub flying — direct flights that do not touch its main hubs at Frankfurt or Munich — in order to maintain its brand attractiveness to corporate clients in Federal Germany. Having found that its germanwings subsidiary had lost the equivalent of the German passenger departure tax per passenger in 2011, and facing deep losses on its non-hub flying, it has increasingly used the LCC to infill routes on its domestic and European services. However, while it thinks that it may have a slightly lower cost advantage at germanwings it is still bound by the national union negotiations within Germany. Until it can develop germanwings bases or subsidiaries outside Germany it is unlikely to be able to establish significantly lower cost operations away from the German unions.

Air France-KLM (faced with medium-haul losses of €750m in 2011) is concentrating on rewriting contracts with its French mainline unions. It is also trying to make more use of the Transavia France as infill, while also trying to develop low cost regionally based operations within the mainline brand on intra-European services. It has the same problems as Lufthansa.

Iberia on the other hand has set up Iberia Express — a move which more closely resembles the union-bashing techniques of the US legacy carriers — with a medium term aim of creating a fleet of 40 A320s operating separately from but in close coordination with the Iberia mainline hub operations at Madrid Barajas. The result so far seems to have exacerbated a lasting stand-off between the Iberia unions and management.

Of all the legacy carriers' responses to LCC incursion, Qantas' Jetstar uniquely seems to be working — at least for the moment. It may involve a lot of smoke and mirrors; it may also be a uniquely Australian, and irreplicable, solution.