Hawaiian Airlines: Asian expansion

Jul/Aug 2010

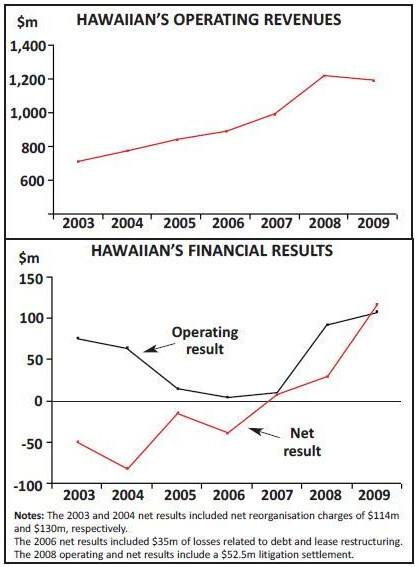

Hawaiian Airlines, an old–established niche carrier, is entering an international growth era that will take it to Japan and South Korea in the next six months and could eventually mean it operating nonstop A330/A350 services to Hawaii from all around Asia. Will the airline succeed in the highly competitive Tokyo- Honolulu market? Will it successfully defend its market shares from aggressive new entrants on Hawaii–US mainland routes? And, most importantly, will it manage to keep costs in check?

Hawaiian has had an eventful five years since emerging from a two–year Chapter 11 reorganisation in June 2005. In the words of its CEO Mark Dunkerley, the airline has had to deal with significant “competitive gyrations” affecting virtually all of its markets.

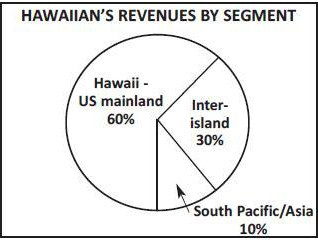

First of all, Hawaiian had to deal with sharply increased industry capacity on Hawaii–US mainland routes, which account for the bulk of its revenues (currently about 60%). Those markets saw a 34% increase in total seats between 2000 and 2005, as all of the large network carriers added capacity and new entrants such as ATA and US Airways joined the fray. The long–haul routes to Hawaii proved an attractive place where to put the capacity removed from mainland domestic service.

Next, the Hawaii inter–island markets, which had had a relatively stable competitive situation for some 60 years (having essentially been a duopoly between Hawaiian and Aloha Airlines), were thrown into turmoil by Mesa’s entry with its new low–fare subsidiary “go!” in June 2006.

Even though go! only operated regional jets, it caused havoc with its aggressive capacity addition and price cutting. To add to the dramas in the two turbulent years that followed, Hawaiian sued Mesa for misuse of confidential information that Mesa had obtained during Hawaiian’s bankruptcy process and eventually received a $52.5m cash payment from Mesa.

In the spring of 2008 Hawaiian’s competitive environment improved dramatically when two of its key rivals, Aloha and ATA, filed for bankruptcy and ceased operations. The result was elimination of overcapacity, a better pricing environment and an opportunity for Hawaiian to recapture market share.

But later that year another (lesser) challenge emerged: Mokulele Airlines, hitherto a single–engine turboprop operator, introduced regional jets and began expanding into Hawaiian’s primary inter–island markets with the help of an investment from Indianapolis–based Republic Holdings (converted to a controlling ownership in March 2009). 2009 saw resumption of price wars as go! and Mokulele jockeyed for the number two position in inter–island markets.

In late 2009 Mesa and Republic decided to combine their Hawaii units into a 75%/25% joint venture (“go! Mokulele”), forming the state’s second–largest inter–island airline. This restored an airline duopoly and a reasonable supply–demand balance in the inter–island market.

The escalated competition in 2005- 2007 meant that Hawaiian’s unit revenues and profit margins came under pressure just as trends on the US mainland had turned positive. The constant turmoil also meant that Hawaiian did not attract any mainstream Wall Street equity coverage following its successful Chapter 11 reorganisation; until very recently, the stock was only covered by smaller brokerages or boutique investment banks.

But things have changed in 2010. In recent months several leading brokerages, including BofA Merrill Lynch and Deutsche Bank, have initiated coverage of Hawaiian. The key positives are the easing of competitive pressures and the recent award of Tokyo Haneda rights, but Hawaiian seems rather well positioned for the future for a large number of reasons.

First, Hawaiian emerged from the turbulent period with significantly improved market shares. It is now the clear leader in the inter–island market, with about 85% of the seats (up from 40% pre–2008).

Second, Hawaiian remained profitable through the 2008 oil price surge and the subsequent global recession – testament to the success of the Chapter 11 restructuring and the resilience of the business model. Including the June quarter, the airline has nine consecutive quarters of profitability under its belt.

Third, Hawaiian has top operational performance, great customer service and a strong brand. It has been the nation’s most punctual airline for six years.

Fourth, the airline has promising long term growth prospects, particularly in Asian international markets. Having won one of only four daily slot–pairs available to US airlines at Tokyo Haneda this year, Hawaiian will launch its first–ever scheduled flights to Japan in October.

Fifth, the long haul fleet plan is in place. Hawaiian is acquiring up to 27 A330/A350s over the next decade.

Sixth, Hawaiian has one of the strongest balance sheets in the industry, making it well positioned to meet the cost of the fleet transition.

Finally, in contrast with much of the rest of the US airline industry, Hawaiian has clinched new contracts with all of its unions in the past 18 months and is therefore into a period of relative labour stability.

But there continues to be a question mark over Hawaiian’s cost structure, which the Chapter 11 process did not adequately address. The past couple of quarters have seen an alarming surge in non–fuel costs.

The business model

Also, Hawaii–US mainland routes are again seeing capacity pressures. Next year is likely to see Allegiant, an aggressive mainland LCC, entering the market with 757s. Hawaiian is one of the oldest US airlines, having operated continuously since 1929, when it was founded as Inter–Island Airways. The present name was adopted in 1941. The airline is currently the 13th largest US domestic carrier in terms of RPMs and operates a primarily–leased fleet of 35 aircraft – 15 717- 200s (inter–island), 18 767–300/300ERs and two A330–200s.

Neither a network carrier nor an LCC, Hawaiian describes itself as a “destination carrier”. The focus is exclusively on the Hawaii state – to bring tourists to the islands and cater for the air travel needs of residents – with little ambition to become more broadly based. The strategy is to “leverage Hawaii’s culture as a competitive advantage”.

In addition to its Hawaii–US mainland and inter–island operations, Hawaiian has a modest South Pacific network (American Samoa, Tahiti and Australia) and has served Manila since 2008. This budding South Pacific/Asian operation currently accounts for less than 10% of its revenues.

Like the legacy carriers, Hawaiian has full capabilities in terms of reservations systems and ability to code–share. It has code–shares in place with a number of airlines, including Island Air, Continental, American Eagle and Korean Air. In addition, numerous airlines place their codes on Hawaiian’s inter–island flights.

As a leisure–oriented carrier, Hawaiian has always had strong load factors but limited pricing power. The inter–island market has been a struggle even in the best of times due to the price sensitivity of the traffic. Because of that and cost issues, up to and including 2002 Hawaiian was a chronically unprofitable airline.

In the long–haul markets, Hawaiian’s key competitive strength is that its business is designed for the niche that it caters for. Its product, services and schedules are all tailored specifically to serve leisure customers coming to Hawaii. The airline also selects only markets where it believes it can have a distinct competitive advantage.

Inter-island: stability returns

After several years of being in a constant flux and evidently producing losses for all carriers, the inter–island markets have seen a return to more rational conditions in 2010. As a result of the go!/Mokulele merger and Hawaiian’s own cuts, industry capacity is well below last year’s level. Although there is still promotional activity, fare levels have risen dramatically. Hawaiian has seen a strong improvement in the financial performance of its inter–island business; PRASM in that market surged by 25% in the March quarter.

This bodes well for Hawaiian as the inter–island business represents about one third of its revenues. The airline has a dominant market share. It offers the most comprehensive schedule and, through interline and code–share relationships, captures much of the connecting traffic arriving in Hawaii on other carriers.

However, it is a shrinking market. Interisland traffic has declined steadily over the past decade or so. The decline is structural and permanent and has two main causes. First, an increase in direct flights from the US mainland to Oahu’s neighbour islands by competitors has meant that fewer people today need to change aircraft at Honolulu. Second, improved infrastructure in the neighbour islands has reduced the need to travel to Honolulu.

This year’s reduced service and higher fares have undoubtedly contributed to the traffic decline. Hawaiian does not separately publish its inter–island statistics, but by some estimates industry traffic may be down as much as 20% this year.

But air travel is now the only means of public transportation between the islands. There has been no inter–island ferry system since the March 2009 demise of SuperFerry.

There is also some uncertainty about go! Mokulele’s future as long as its operator and 75%-owner Mesa is in bankruptcy. Mesa filed for Chapter 11 in January 2010 mainly to shed numerous unwanted 50- seat RJs. Although the JV was not part of the Chapter 11 filing, can Mesa justify retaining what is believed to be a loss–making venture?

Another development probably in Hawaiian’s favour is that after Aloha’s sudden demise — described as a “seismic” event in Hawaii because the carrier had moved about 40% of the inter–island market – the Hawaiian legislature proposed new tighter regulations on the inter–island market. If enacted, there could be tighter controls on airline entry, fares, schedules and ownership transactions.

After Aloha’s demise, Hawaiian worked hard to “prevent a meltdown” in the state’s transportation system. It immediately stepped up operations by utilising a spare 767–300 and leasing four additional 717s. It hired many former Aloha workers, while its own employees worked overtime for five months.

Transpacific challenges

Adding all of this up, Hawaiian may have secured a dominant “hometown airline” role in the inter–island markets for the longer–term – a good position to have for supporting expansion in long–haul markets. The Hawaii–US mainland routes have remained highly competitive, seeing new entrants (such as Alaska in 2007) and continued capacity addition by the network carriers. One of the attractions has been the absence of mainland LCCs – they do not have the aircraft with sufficient range.

However, Hawaiian has been able to gradually increase its market share, and in 2007 it overtook United as the largest carrier in the market. It currently has 28% of the seats, with United being a close second with a 25% share. Three other carriers – Delta, American and Alaska – have 10–15% shares each.

Hawaiian has been able to take advantage of voids that have appeared in the marketplace. When American vacated San Jose–Honolulu, Hawaiian quickly stepped in. And when Oakland lost both of its carriers to Honolulu (ATA and Aloha), Hawaiian swiftly launched a daily service on that route.

The two bankruptcies had a major, albeit temporary, impact on the transpacific market. Before its closure, ATA had 12% of the seats, with service to Hawaii from four points on the mainland. Aloha had provided about 6% of the Hawaii–US mainland capacity, operating scheduled service to multiple mainland cities.

In addition to having the largest market share, Hawaiian also has the most comprehensive set of US West Coast gateways to Hawaii: currently 10 — San Diego, Phoenix, Los Angeles, Las Vegas, San Jose, San Francisco, Oakland, Sacramento, Portland and Seattle. All of those cities are linked to Honolulu and some also to Kahului.

The large network carriers have many competitive advantages. They generate traffic from throughout the US mainland. They operate from hubs, which can provide a built–in market for passengers; for example, United flows sufficient passengers from all around the mainland to schedule up to nine daily San Francisco- Hawaii flights (depending on the season), whereas Hawaiian only has one. In addition, the point of sale is mostly on the US mainland, not Hawaii.

But Hawaiian has its own unique competitive advantages, namely a higher level of customer service and a product and operation that are specifically tailored for the Hawaii–bound leisure customer.

One interesting example: Hawaiian schedules its transpacific flights for the local customer on the West Coast, rather than to connect with any feeder flights (because it does not have any). Its flights depart the West Coast much earlier in the day than the legacy carriers’ flights, giving its customers an extra afternoon on Hawaii. This is somewhat of a creating a virtue out of necessity, but the West Coast is a very important generator of leisure traffic to Hawaii and local traffic tends to be higher–yield.

The A330–200s will enable Hawaiian to further enhance its transpacific product offering. The first two aircraft were deployed in June on the Los Angeles route and to launch new seasonal service from Maui to Oakland and San Diego. The third aircraft, due to arrive in November, is currently earmarked for the Las Vegas market.

Hawaii–US mainland routes did see a dip in travel demand due to recession last year, but it was much less pronounced than in other markets. Consequently, this year’s recovery trends are not as spectacular as elsewhere. In 2010 visitor arrivals in Hawaii from the mainland remain comparable to 2008 levels but well below 2007’s peak.

Hawaiian currently projects industry capacity on Hawaii–US mainland routes to increase by 9% in 2010 – a higher rate than even in most international markets, though this year’s capacity to Hawaii would still be 9% below 2007’s level.

The additional capacity is coming from a number of carriers, including Alaska and Continental. Alaska operates directly to the smaller islands with 737–800 ETOPS, avoiding all the widebody competition on the Honolulu routes. Its latest addition was Sacramento–Kahului in March, and planned service to Kauai from San Jose and Oakland from March 2011 will bring the Hawaii service to 100–plus weekly flights to four islands. The services are supported by Alaska’s vacations unit and also make much sense from the FFP point of view.

But the most notable new development is Allegiant’s plan to enter the US mainland–Hawaii market, most likely in the first half of 2011. The Las Vegas–based LCC, which currently operates MD–80s, is acquiring six 757–200 ETOPS and hopes to extend to Hawaii its hugely successful mainland strategy of serving large leisure destinations from smaller cities with no existing nonstop service (see article, pages 5–7).

Allegiant is to be taken seriously because it has grown aggressively, is highly profitable and has a significant cost advantage against all other US airlines. It will also compete in a slightly different way: it is in the business of selling “travel” (also hotels, car hire, show tickets, attractions) – something that may prompt Hawaiian to accelerate its own efforts to generate ancillary revenues.

Then again, Allegiant is very much a niche operator. It avoids competition and will be operating from the type of medium- sized cities that Hawaiian is not interested in (the likes of Bellingham, Stockton and Fresno are believed to be on the short list).

Hawaiian is used to dealing with competition from all comers. Furthermore, since Allegiant is likely to operate to Honolulu and Maui (rather than to the outer islands), there could even be an upside, namely that Allegiant’s transpacific services could bring incremental passengers to Hawaiian’s inter–island network. The same is true for the other transpacific competitors. CEO Mark Dunkerley commented recently: “We compete with all the airlines tooth and nail over the Pacific and at the same time we do carry a lot of their connecting customers inter–island”.

Asian opportunities

Given its success on the West Coast and the capabilities of the future long range fleet, does Eastern US feature at all in Hawaiian’s expansion plans? CFO Peter Ingram explained at a recent conference that Hawaiian is not interested in the large population centres in the middle of the country, because they are generally other airlines’ hubs, but that large East Coast cities such as New York or Boston are a possibility because they are generally spoke cities. But Ingram noted that the East Coast cities already have plenty of connecting service to Hawaii. Since the traffic is primarily leisure customers who are paying with their own money, they are not prepared to pay a significant premium for the convenience of nonstop service. Hawaiian’s leadership considers the international markets in Asia “probably the number one opportunity for us in the years ahead”. After dipping its toe in with Sydney (2005) and Manila (2008), the airline is now gearing for the launch of Tokyo on October 31 and Seoul in January 2011.

The launch of Tokyo is a watershed event for the company because Japan is the second most important source of visitors for Hawaii (after the Western US). Japan–Hawaii is a very large market with intense competition. However, it is also a very mature market and has been declining in the past 10–15 years, so Hawaiian was previously concerned about the prospect of coming in as a marginal competitor. Securing rights to Haneda, which is much closer to downtown Tokyo than Narita and offers full access to JAL’s and ANA’s domestic networks, has made all the difference. Calling Haneda a “premium piece of network real estate”, Hawaiian’s management believes that Haneda offers a “terrific way to not only get our foot in the door but gain a very strong position to Japan”.

Hawaiian does have plenty of broader Japan experience. In the 1980s and 1990s it operated the largest charter programme between the US and Japan. It already has a Japanese language web site and has had a sales presence in Tokyo since 1973.

Hawaiian got rights to only one daily frequency to Tokyo but hopes to secure a second flight in the future. However, the airline believes that it can make money with only one daily flight. It will initially utilise 264–seat 767–300ERs and later 294–seat A330s. In terms of CASM, in some respects it will be very efficient flying, but infrastructure costs will be high. Similar to its US West Coast strategy, Hawaiian hopes to capture market share with its distinctive “Hawaii Starts Here” on board service and by timing its flights from Tokyo to allow visitors to maximise their time in Hawaii.

The Seoul–Honolulu service, to be launched in January initially with four 767–300ER flights per week, will tap into the important South Korea visitor market, which offers potential for growth also because of its recent addition to the US visa waiver programme. Seoul’s Incheon, one of Asia’s largest hubs, can also feed traffic to Hawaiian’s flights from all over the region. This is a fairly risk–free move also because it is done in the context of an existing code–share relationship with Korean Air, which has already operated Seoul–Honolulu for some time.

It is widely believed that a route between Hawaii and mainland China is also in the works. Also, Hawaiian will be looking at other opportunities in Japan, which is by far the most mature market in Asia for travel to Hawaii.

Hawaiian’s management believes that people in Asia’s developing economies, such as Korea and China, will have the same affinity for travel to Hawaii as the Japanese do. The islands offer a unique mix of Asian and American culture and much natural beauty and wonder that are very attractive to people from that part of the world. But in some countries there may be a need to build awareness of Hawaii as a destination, so Hawaiian’s Asian expansion will not be an all–at–once type of phenomenon.

One interesting question is whether Hawaiian might in the future carry Asia–US mainland connecting traffic. It could market Hawaii as a vacation stopover for both US mainland and Asia–originating passengers.

The A330s and A350s will replace the current 767 fleet over a decade, provide for growth at a “responsible” rate and enable the airline to serve virtually any major visitor market in the world. With many of the deliveries timed to coincide with 767 lease expirations, there is much flexibility to scale growth to market conditions. In addition to the three leased A330–200s taken this year, Hawaiian has seven more of that type on firm order from Airbus, for delivery in 2011–2014, plus five purchase options. It also has six A350XWB–800s on firm order, for delivery in 2017–2020, plus six purchase options.

Two years of pretax profits and cash generation have put Hawaiian in a good position to meet the higher capex associated with the fleet plan. However, this year is likely to see its earnings dip, contrasting with the improvements reported by the rest of the industry. This is in part because Hawaiian suffered less than its peers in 2009; in fact, it had a highly profitable year, helped by its leisure focus and very low fuel costs in the first half. In 2010 it is seeing higher fuel prices and significant cost inflation in many non–fuel items. So, in addition to managing new international expansion, Hawaiian has to tighten cost controls and get some unit revenue improvements at least in the more stable inter–island market.