Airport valuations - market correction

Jul/Aug 2009

Strong demand for airport assets, limited supply and the availability of relatively cheap debt made airport transactions one of the most dynamic sectors in aviation finance in recent years. Inevitably, the recession and the credit crunch has changed perceptions of values.

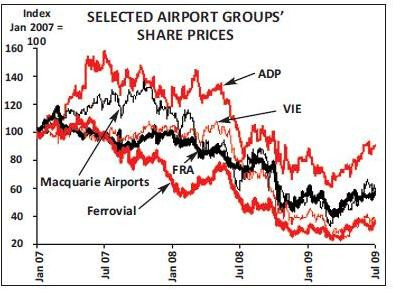

Quoted airport shares have held up reasonably well – on average only 50% down from the peak in 2007, having bottomed at around 60% down. Some have fared worse. Ferrovial (BAA), Gemina (FCO) and Flughafen Wien (VIE) each saw their shares slump by 80%; the latter two a result of the dire circumstances of their respective hub carriers, Alitalia and Austrian; the former beset by the general woes of the Spanish economy as well as the broadside attack from the UK authorities demanding a breakup of BAA’s seeming monopoly over the London and Scottish lowland airports.

The quoted airport sector, however, is relatively small even though it encompasses some of the largest airports in the world outside the US (where airport privatisation has never really caught on). It may appear nevertheless that private airport valuations could also have peaked in 2007/08 – although since the collapse of Lehman Bros last year there has not really been any real volume of transactions to suggest a meaningful trend.

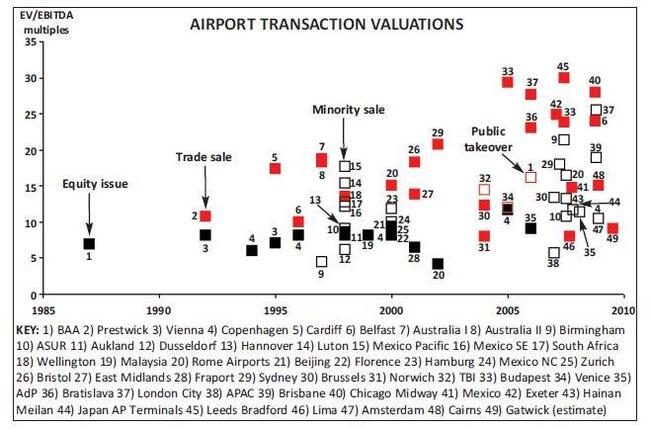

Of course the airport market is still relatively young. Margaret Thatcher started the process with the privatisation of BAA 22 years ago, and since then there has been a smattering of IPOs and public market equity issues — the last being Aéroports de Paris in 2006 — sold on an average of just over eight times Enterprise Value (equity market value plus net debt) to EDITDA (operating cash flow). Equity markets have somewhat differing views of valuation from some private equity and corporate entities – and very long–term investments such as airports may be difficult to digest by a market sometimes dominated by thoughts of the next quarter’s returns. (Although it is perhaps interesting to note that an investment in BAA held from privatisation in 1987 to take–out by Ferrovial in 2006 would have produced a 15% average annual total return.)

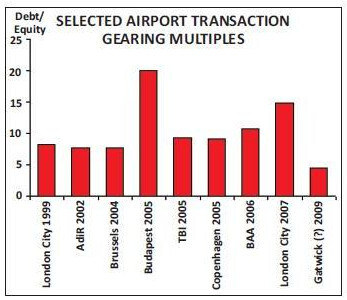

Private equity deals meanwhile, and trade sales, have generally achieved far higher sale multiples — on average, up to the end of 2008 at least, of more than twice that of the public markets at over 17 x EV/EBITDA. This average, however, is rather heavily weighted to some (continued on page 2) notable transactions from 2005 and onwards, including Budapest and London City (and would be even higher if the aborted Bratislava and Chicago Midway transactions had gone through) – with stratospheric multiples of nearer 30x.

Airport fundamentals

In some cases the apparently high valuations may have been because the purchaser identified higher potential future returns from a small airport otherwise seen to be difficult to sell to the public markets. In others, it was the finance community’s tendency to follow initially very successful funds (such as the Macquarie Airport Group) that increased the demand for the few airports available for investment. In part it was also due to the very availability of cheap debt, and the appetite for risk that allowed small amounts of equity to appear to be able to support substantial levels of gearing. Very usefully there is the general overriding principle in the ICAO Chicago Convention (Article 15) that airlines should pay in full for the use of aviation infrastructure — interpreted as giving an airport the right to charge airlines landing fees commensurate with the cost of providing the service plus an adequate return on capital investment irrespective of market conditions. This principle of course springs from the days when almost all airports were government- or local authority–run, and it does reflect the long–term highly capital–intensive nature of building the infrastructure. But this also by its nature helps create the view that it airports are monopolies – at least in local terms – bringing in the political need to regulate the finances to ensure no monopolistic market abuse.

As a result, we have all the wonderful permutations of control from the “single till” approach, where all returns on a regulated asset base are supposedly limited to a politically acceptable return above weighted average cost of capital (and may encourage spending, as Ryanair’s O'Leary complains, without necessary regard to economy, or to airline users' needs); to the $1 pragmatic consultative regulation of some such as Denmark; to the “double till” approach that limits returns on charges for infrastructure to the airlines but allows the airport to screw what it can from everyone else. Few of the regulatory regimes really consider operating costs – primarily staff and power – to be within their remit.

Meanwhile, the business is truly long term and requires excellent long–term planning. It is somewhat ironic that a successful airport attracts businesses, jobs and accommodation needs close by those who then become affected by the incumbent noise and congestion (and even those who enjoy the benefits of being able to use the facility) and who complain about attempts at expansion – with ever–increasing pressure from environmental groups mistakenly convinced that aviation is the greatest contributor to climate change.

So airports enter the political arena, to complicate the business planning process further. As a result, in many countries (such as Germany, the UK, Spain) it can take decades to prepare even to consider building a new runway or new terminal facilities and the delays in the planning process for the fifth terminal at London Heathrow, or the fourth runway and third terminal at Frankfurt, have managed to provide severe congestion bottlenecks.

Even in the early 1980s the British Airports Authority (the precursor of BAA) was already planning for the need to knock down the Queen’s Building and Terminals 1 and 2 at Heathrow by 2012 (a process just started), even before they had finished T4 or allowed plans for T5 to leak out. In one sense it may be argued that an airport should not expand and should allow traffic to be turned away to other destinations, but then of course there would be even more political complaints.

The long–term nature of the airport business feeds into the valuation process for airport transactions. The main driver for the development of the business is traffic growth – dependent as we all know on performance of GDP (worldwide, local and trading partners) and airline capacity. Many of these valuation models require detailed 30+ year forecasts of traffic; traditionally these are built from a short–term bottom–up approach extracted from existing airline schedules, known route development plans and short–term traffic trends, melded in with long–term econometric top–down modelling. From this derives all the modelled capital spending needs, costs and, combined with assumptions on revenue generation, returns over a generation. This is always a challenging exercise (considering that the whole industry only just celebrated its centenary last year), and that debt providers (for whom much of the modelling is really done) have a tendency to focus on little more than a year or two, even though the debt maturities can extend for half the modelled period. The resulting cash flow stream from the model is then discounted back at the rate of your choice to generate the valuation, or range of valuations. In all DCF models the early years weigh significantly higher in the net present value of the income stream – and at the moment, with traffic volumes continuing to crater, the pressure on short–term forecasts can be intense.

It is hardly surprising therefore that the deal of the year – Ferrovial’s disposal of London Gatwick – has not gone entirely smoothly. When Grupo Ferrovial and its partners acquired BAA in 2006 they must have little expectation that they would be kicked so hard. The terrorist attacks in London that year and the resultant increases in security requirements (along with the ban on liquids and restrictions on duty–free) and the results of the quinquennial regulatory review were bad enough – but then to find out that the establishment could now use the foreign takeover of a national asset as a catalyst to respond to demands for a breakup of the 21–year old private airport system on the basis that it was an unacceptable monopoly must have been severely galling. As a pre–emptive move the group put London Gatwick on the sale block towards the end of last year.

After a first round knockout, only three bidding groups were left in the running, deadlines were extended after the arrival of Mexican flu, and the bids were disappointing from Ferrovial’s perspective. While the Spanish conglomerate was expecting some premium to the £1.6 million Regulated Asset Base (a theoretical balance sheet valuation used in regulating fees at the airport) all three consortia apparently bid well under. There was a major gap between the seller’s and the buyers’ views of airport value. Optimistically assuming a successful bid of around £1.5bn for Gatwick would produce an EV/EBITDA multiple of around 9x – a significant drop from the 16x achieved when Ferrovial and its partners acquired BAA.

BAA has appealed against the findings of the final competition report, which was published in March and recommended that BAA dispose of two of its London (i.e. Gatwick and Stansted) and one of the lowland Scottish airports.

The case is being held at the Competition Commission Tribunal in October. This will certainly help delay the enforcement orders and may provide enough time for a pickup in asset values; although a forced seller is never in a good position whatever the time of the cycle. Some may of course doubt that there could be much demand for Stansted, given the nature of the base carrier — Ryanair.

The return of privatisation

Just to add even more uncertainty, the DfT is expected to publish its proposals for future regulation of the UK airports – to provide the basis to update the 1986 Airports Act – in the autumn. However, the economy will at some point recover and confidence will no doubt return to allow people to travel again; air travel growth may then follow a lower trend as some suggest, but there will undoubtedly still be growth. Importantly, the arguments for airport privatisation are still valid. Figures from the ACI earlier this year suggested that worldwide airport capital spending would top $50bn again in 2009 (more than 50% of industry turnover). China still plans to build 200 new airports over the next decade. The money will need to be found – and governments and local authorities now have less of that available than they previously thought.

| Revenues | Y-O-Y | EBITDA | Y-O-Y | Traffic | Y-O-Y | ||||||

| Heathrow | £m | change | £m | change | m | change | |||||

| 1,486.4 | -18% | 594.3 | -27% | 66.9 | -1% | ||||||

| Gatwick | 464.6 | -22% | 174.0 | -22% | 34.2 | -3% | |||||

| Stansted | 258.4 | -27% | 113.8 | -32% | 22.3 | -6% | |||||

| Scotland | 214.5 | -31% | 107.7 | -29% | 20.4 | -5% | |||||

| Southampton | 26.4 | -25% | 8.0 | -35% | 2.0 | -1% | |||||

| Heathrow Express 156.5 | -21% | 41.5 | -22% | na | na | ||||||

| UK total | 2,606.8 | -21% | 1,039.2 | -27% | 145.8 | -3% | |||||

| Naples | 47.7 | -19% | 14.4 | -20% | 5.6 | -2% | |||||

| Total | 2,654.4 | -21% | 1,053.6 | -27% | 151.4 | -3% | |||||