JetBlue: Rationale behind the Embraer order

Jul/Aug 2003

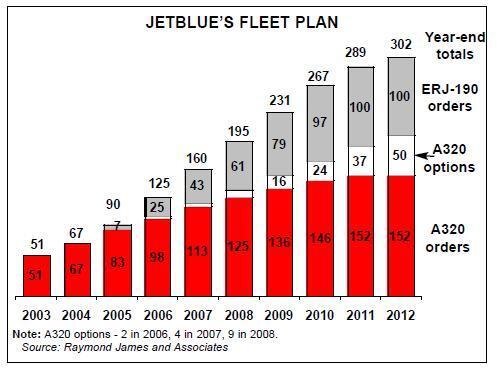

JetBlue Airways' recent decision to order 100–seat Embraer ERJ–190s to supplement its Airbus A320 fleet from mid–2005 surprised many in the industry.

First, the airline is breaking the conventional wisdom that operating a single aircraft type in the 150- seat category is critical for the Southwest/JetBlue–style low–cost strategy.

Second, it is departing from that model rather radically by opting for what is generally regarded as a regional jet.

In brief, people are wondering why JetBlue, which built its success on extremely low costs and obviously has further exciting A320 growth opportunities, is interested in smaller markets and an aircraft type that falls somewhere between commuter carriers' 70–seat RJs and larger airlines' 110–115 seat jets. Why not just continue A320 expansion? It is worth noting that the launch order for 100 ERJ 190–100LRs and 100 options, announced on June 10, will not have any impact for two years, because first deliveries will not take place until mid–2005.

JetBlue will receive only seven ERJ–190s that year, with the rest of the firm order arriving at a rate of about 18 aircraft per year through 2011.

However, there is much interest in the rationale behind JetBlue’s ERJ–190 decision, because other low–cost carriers on both sides of the Atlantic are grappling with similar decisions. After faithfully following the Southwest formula, the airlines are now wondering whether a second fleet type might make sense, given the current low aircraft acquisition costs and new types of market opportunities (often resulting from larger carriers' downsizing).

JetBlue, of course, had to make sure that its employees, shareholders and the financial community understood the ERJ–190 decision, which the management team apparently supported unanimously. CEO David Neeleman and CFO John Owen went to great lengths to explain the rationale at a conference call and at Merrill Lynch’s annual transportation conference, before embarking on a national tour to meet employees.

Going for smaller markets

JetBlue is ordering a smaller aircraft type because it has spotted a good additional growth opportunity in medium–sized markets that are too small for the A320. Its analyses identified almost 900 potential markets with daily volumes of 200–500 one–way passengers that did not yet benefit from low fares.

By comparison, there are 305 markets with 600–plus daily passengers — the types of routes that the A320 is best suited to.

The airline believes that many of the medium–sized markets (200–500 passengers) could be stimulated to grow to 600- plus passenger markets, but it would be too risky and expensive to go in with a high–frequency A320 operation.

The ERJ–190 can provide the needed frequencies with much less risk and a lower break–even load factor (apparently only "a little over 60 people" or 60%, compared to the A320’s 119 passengers or 73%).

The ERJ–190 could also be used to develop some of the 807 smaller 50–100 passenger markets identified by the airline’s analyses. For example, in the New York- Burlington (Vermont) market JetBlue has more than doubled the original daily traffic volume of 100 passengers with two flights a day (but that is till not enough to make a profit with the A320).

In addition, the second aircraft type is likely to improve synergies in the route system, particularly in the off–season, and help spread overhead costs. For example, JetBlue could fly Syracuse (NY)-Florida in the winter, connecting cities that are already served separately from JFK.

While both Southwest and JetBlue go for under–served, over–priced markets that can be stimulated with low fares and like to rapidly build up frequencies, there are two important differences in their growth strategies. First, Southwest only wants to serve relatively large markets, while JetBlue is also interested in medium–sized and some small markets (such as those linking NYC with upstate and New England cities — routes that help it maintain local and national political support). JetBlue wants to serve "markets of all sizes across the US" (according to its press release).

Second, there is a dramatic difference in growth rates. Southwest has always grown at a very conservative pace (it took 12 years to get to 50 aircraft), whereas JetBlue will have reached 54 aircraft in less than four years (by the end of 2003) and intends to continue to grow extremely rapidly.

Bearing in mind these differences, it is easy to see that JetBlue could benefit significantly from the flexibility offered by two aircraft types of sufficiently different sizes.

(Otherwise, the JetBlue executives made the point that Southwest effectively operates two or three different aircraft types — the 737- 200, 737–300 and 737–700.

Others might add that there are substantial commonality benefits.)

JetBlue is not slowing growth planned for the A320. After placing another massive order for up to 115 A320s in April, the current Airbus fleet will almost quadruple to 202 aircraft by 2012 if all of the options are exercised (which has so far always been the case with JetBlue).

The ERJ–190 will simply add to the planned A320 expansion, helping JetBlue maintain extremely rapid growth in the second half of the decade when the A320 growth rate begins to taper off.

The airline expects to maintain a 24–25% compound annual ASM growth rate in 2003–2011, which would be a stunning achievement when considering that JetBlue is no longer that small.

Why the ERJ-190?

JetBlue began evaluating smaller aircraft types about nine months ago and also looked at the Boeing 717, the Airbus A318 and the Bombardier CRJ–900. The 717 and the A318 were considered too large — and the A318 could not take the IAE V2500–A5 engines that power the carrier’s A320s.

The CRJ–900, in turn, did not meet JetBlue’s very exacting standards of roominess and cabin comfort.

The JetBlue executives indicated that maintaining what they described as "the JetBlue experience" was a key requirement.

The ERJ–190 apparently has the look and feel of a small jet (rather than a regional jet) and can offer the same comforts as JetBlue’s A320s, including the famous roomy leather seats, 32–inch seat pitch and even wider aisles.

The aircraft will have 100 seats in single class, two–by–two configuration and, like the A320s, will offer DIRECTV satellite programming at every seat.

CFO John Owen said that JetBlue regards the ERJ–190 (which it calls "EMBRAER 190"), with its 100 seats and 2,100–mile range, as "much more like a replacement for a DC–9–30" than a regional jet. Most people think of it as an RJ (with the higher costs and inferior comfort connotations) simply because Embraer has a history of building regional jets.

Owen contrasted JetBlue’s plans with the way that other airlines, when contracting with small regional carriers, "water down the experience with their airline" because of cramped quarters in their partners' regional jets. Of course, pilot scope clauses limit many US major carriers to 50–70 seat RJs.

With this move JetBlue is obviously positioning itself for more head–to–head confrontation with competitors' RJs.

It was attracted to the ERJ–190 also because of what Owen described as "artificial economy in the sizes of aircraft" created by scope clauses. Its future 100–seaters flying 11 hours a day will have a huge efficiency advantage over competitors' 50–seat RJs flying typically eight hours a day.

The executives argued that even a 70- seater was too small to stimulate traffic (contrasting JetBlue’s strategy with that of US Airways, which in May became the launch customer for the 70–seat ERJ–170).

Although in the future more scope clauses will include larger RJs, JetBlue feels that the trend is so gradual that it will retain a competitive advantage for many years to come.

JetBlue also liked the fact that the ERJ- 190 is an all–new aircraft — Embraer started with a clean sheet of paper with the fuselage cross–section, not unlike what Airbus did with the A320 in the mid–1980s. "As you stretch or shrink an aircraft, the further you get from the original, the less optimal it becomes in performance", the executives noted.

Of course, the ERJ–190 benefits from being part of a family that Embraer is developing to fill the gap in the market for 70–110 seat jets. It is not yet type certified, but it features advanced technology that has already been tested on the other models, including integrated avionics and fly–by–wire flight controls. It will be powered by GE’s latest, most powerful CF34–10 engines.

Comparative pricing is not believed to have been a deciding factor, with Embraer, Airbus and Boeing all offering highly attractive deals (Bombardier is believed not to have made a formal offer). That said, such launch orders always involve extra special discounts prices and generous product support packages.

The price widely quoted was $6bn for the whole deal, but this is based on Embraer’s list prices, and bears little resemblance to the actual, much lower price negotiated.

CASM and profit impact

Rather surprisingly, JetBlue’s financial analyses suggested that the ERJ–190 would generate profit margins that are comparable or better than those achieved with the A320.

The ERJ–190 is expected to have a one–cent unit cost (CASM) premium over the A320 on comparable stage lengths, but the airline is confident that it will be able to compensate for that on the revenue side.

In theory it sounds perfectly feasible. For example, on the 300–mile NYC–Buffalo route the ERJ–190 would cost $3 more per seat to operate than the A320. The current average fare of $60–64 would be raised to $65–69 on the ERJ–190. The additional $5 would be enough to improve the profit margin but it should not have negative impact on demand, given that the original (only slightly lower) fare was 50–60% below what other carriers were charging before JetBlue’s entry.

In other words, JetBlue should be able to continue to stimulate traffic in new markets just as well with the ERJ–190. It may succeed even better because the aircraft would be utilised in shorter–haul markets, where the best price–cutting opportunities tend to be.

In any case, JetBlue has proved in the past in the highly competitive Northeast- Florida markets that, after competitors have responded to its entry, it does not have to offer the lowest fare to win market share battles.

This is because it has been able to build strong customer loyalty based on a superior product and service quality.

The ERJ–190 will obviously have higher fuel, maintenance, pilot training and airport costs per seat than the A320. However, flight and cabin crew costs per seat will be similar because pay rates on the ERJ–190 will be lower. JetBlue does not see this creating problems, because current pilots will not be asked to take pay cuts and because the ERJ–190s will supplement (rather than replace) A320 growth.

Other airlines will pay more to operate the ERJ–190 because JetBlue’s cost calculations assume average daily aircraft utilisation of 11 hours and other unique efficiencies. The CASM difference between the A320 and the ERJ–190 will in reality be greater than one cent, because the ERJ–190 will typically be deployed on shorter stage lengths.

However, because the airline will continue to operate a much larger number of A320s (which have more seats), the negative impact on overall unit costs is not expected to be that significant.

Owen estimates that in 2009 the ERJ- 190’s average stage length will be about 600 miles, compared to the A320’s 1,200 miles. There would be roughly twice as many A320s. As a result, total CASM would be about half a cent higher than with an all- A320 fleet.

In 2002 JetBlue’s CASM was just 6.43 cents, representing a very comfortable lead over the rest of the industry. Half a cent more would have taken it to 7 cents — still below Southwest’s CASM but not by a large margin.

Is this a risky strategy?

One worry among investors has been that the move to shorter–haul markets might take JetBlue to head–to–head confrontations with Southwest. This was strongly denied by the JetBlue executives, who said that Southwest was not present anywhere near the markets that were being considered.

For one thing, Southwest needs bigger markets for its 150–seaters. Also, neither Southwest nor JetBlue is interested in markets that have already been stimulated with low fares.

There would appear to be plenty of separate growth opportunities left for both airlines for many more years.

As to the risk of costs creeping up as a result of the ERJ–190 strategy, it is worth noting that AirTran has managed to stay highly cost efficient and profitable with a two–type fleet. Its CASM is only around 8 cents, even though it operates 717s and DC–9s (which it is phasing out) and has a rolling hub (JetBlue is point–to–point).

Like JetBlue, AirTran feels that its future growth opportunities dictate a second aircraft type and that now is a good time to be placing major orders. However, with its recent 737–700/800 purchase, AirTran is moving in the conventional direction of 150- seaters.

While some analysts may not be totally comfortable with JetBlue’s ERJ–190 strategy, they hold the airline’s management team in such high regard that they are giving them the benefit of the doubt. The consensus opinion is that the benefits of the strategy will outweigh risks and that the additional growth will create long–term shareholder value.

As is often the case with growth strategies, the biggest risk is likely to be execution. JetBlue will need more terminal space at New York JFK — it is confident of securing it either on an interim or permanent basis (it hopes to get its own terminal facility eventually).

It will need to construct new training facilities and be involved in the ERJ–190 certification process, while continuing to rapidly grow A320 operations. JetBlue officials have indicated that there is relief all around that the ERJ–190 will not arrive for another two years.

Thanks to ample reserves and continued healthy cash generation, JetBlue should be able to execute its growth plans.

The first 30 ERJ–190s will be taken on operating lease from GECAS, which means that the airline will not need to seek financing for the rest of the new order until 2007.

A few weeks after the ERJ–190 order announcement, on July 3, JetBlue filed plans with the SEC to complete a $128.6m secondary public offering. This would follow from the hugely successful April 2002 IPO.

It will help raise funds for expansion, preventing the balance sheet from becoming excessively leveraged. At the end of 2002, total debt accounted for a still–manageable 63.2% of capitalisation, but there are significant operating lease obligations.

The secondary stock offering will undoubtedly be a success. JetBlue has gone totally against the industry trend since September 11 by posting strong quarterly profits. It has had five consecutive quarters of double–digit operating margins (15.9% in the March quarter).

Its per–share earnings are expected to improve by 30–40% annually over the next few years.