The cross-functional airline challenge

Jul/Aug 2001

Once airline managers have become proficient at processes, they then have to tackle cross–functional activities. This is McKinsey’s analysis of the challenge.

By their very nature many airline activities are well suited to be run using a strong process orientation, as they are linked to specific deadlines or to the calendar, with clearly specified end products. Network planning, scheduling, crew planning, crew assignment, maintenance planning, revenue management, and account planning are all processes that must deliver a specific end product at a specific point in time. The process nature of airlines is typically reflected in their organisational structure, and many organisational units are defined in a way that they optimally cover a specific process. As well, the skills and competencies to solve complex function–related issues reside within the corresponding organisational unit. Many processes can count on sophisticated IT support to handle large amounts of data, automate tasks, carry out simulations and to optimise profitability.

Other activities, that are not recurring and not linked to a pre–defined deadline, are often carried out as projects: the evaluation of new product configurations, the development of a new distribution channel or loyalty schemes, new fleet evaluations, major network redesigns, etc.

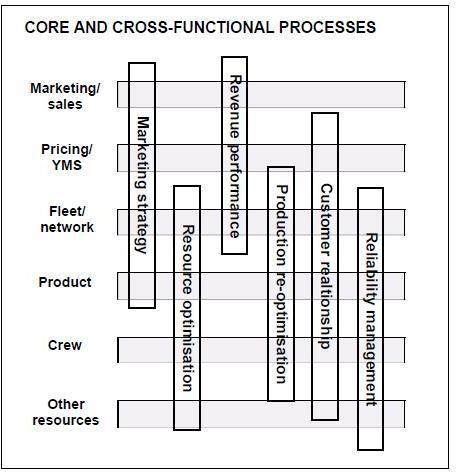

Then there is a third, crucial type of activity that cuts across core processes and functions: the cross–functional processes. Given the high level of specialisation within different processes or functions, organisational units tend to work in relative isolation from the rest of the airline, focussed on their parameters and their objectives. Over time, cross–functional management has become more and more a senior management task, with many issues to be resolved through hierarchy instead through well–working cross–functional processes.

Six cross–functional processes can be defined that are of potentially high value to an airline (see diagram on page 16).

Marketing strategy process

What airlines normally label "marketing" is in most cases one single "P" (Promotion) from the classical "4Ps" of the marketing mix (Product, Price, Place, Promotion). "Strategic marketing" typically includes brand building and general advertising activities, as well as a Frequent Flyer Program, while "tactical marketing" is more specific market or route promotion to stimulate demand when load factors are low. The 4Ps are spread across at least 4 or 5 processes, such as fleet planning, network planning and product management (Product), sales (Place, i.e., the management of the distribution channels) and pricing. Each of these processes or departments considers customers from a different angle:

- For network planning, customers are simply heads along specific O/Ds with average yields attached to them

- Product management will think along the classic short–haul vs. long–haul and compartment dimensions

- For sales the customers might well be the intermediaries (as opposed to the end consumers)

- "Marketing" departments typically segment customers according to accrued miles. More sophisticated marketing departments might well have advanced segmentations along all possible socio–demographic or behavioural attributes, but these are typically stand–alone considerations with no or limited impact on the rest of the airline.

One could argue that dealing with the 4Ps is ultimately about airline strategy and this should be a senior management task. This is true — the marketing strategy process is not a replacement for an airline’s strategy process, the way to set frame conditions in terms of overall positioning, growth, network and fleet strategy, alliance and consolidation strategy, etc. or, in other words, the structural aspects and the "hardware". But the marketing strategy can and should play a pivotal role with respect to the strategy process. It can:

— Provide substantial input to the strategy process, bringing in a more fundamental view of customer segments, including a clear picture of customer segments' needs, attractiveness (size, growth, profitability) and competitive position

— Link strategy, marketing and sales activities, as well as some of the product elements, i.e., convert strategy into marketing actions, focus the organisation on its key priorities, and integrate and balance marketing and sales activities across functions and geographical boundaries (or, to put it differently, to provide the "software"). For this a well–structured and disciplined cross–functional process with a clear end product, an integrated marketing and sales plan, is needed. This plan should be the basic vehicle for creating a common language and spell out joint understanding of the marketing mix, segment by segment, and detail activities in all relevant areas.

Revenue performance management process

Airlines typically manage performance through two management processes:

- Regular reviews of the performance of all routes and their contribution to overall network profitability: this is usually done several weeks (if not months) after the schedule has been flown, and very often measures concerning the schedule take time to implement.

- Regular screening of advanced bookings to spot areas of weakness in the way revenues are developing vs. the budget: this is the way sales and marketing decide on additional revenue–generating measures, which in most cases will be price–based promotions.

Very often there is a disconnection between these two processes, not only in terms of timing (one dealing with past performance, the other dealing with future revenues), but also in terms of measuring performance and the types of actions that are considered. In particular, measuring revenue performance is not an obvious task: route–based profitability considers revenue performance is sufficient if allocated costs are covered, the sales organisation works with indices based on the previous year’s revenues.

In a really cross–functional revenue performance process all revenue–influencing departments would be involved, i.e., scheduling (current schedule management), sales, marketing, pricing, and revenue management, working with both past and prospective performance indicators reflecting the absolute revenue performance market by market (i.e., O/D by O/D). They would jointly consider the full set of possible actions to deliver the most effective answer to a revenue opportunity (as opposed to pricing promotions just in the event of revenue problems), based on a clear, fact–based diagnostic showing why a specific market is performing below its absolute achievable performance (given the structural conditions, and based on comparison with other comparable markets). Then the full range of revenue–enhancing actions should be considered: price increases or decreases, capacity adjustments, regular channel actions, tactical promotions, availability of specific booking classes, etc. should be developed, quantified, and run in a coordinated way. This would imply a change in mindset about the way revenues are steered, a disciplined and analytic approach, and the creation of a jointly agreed fact base (see "Who is responsible for revenue?" Aviation Strategy, April 2001).

Resource optimisation process

Although IT and algorithm advancements have been substantial in the past few years, the resource optimisation process of airlines, i.e., the optimal matching of resources such as aircraft, crews, and maintenance to a schedule, is still largely a sequential process: network planning develops a schedule, fleet types are assigned to the schedule, scheduling performs the aircraft rotations, crew planning the crew rotations, crew assignment assign names to the crew rotations,and so on. Of course there are some feedback loops in the overall processes, but essentially all these processes and the associated IT tools optimise their specific end products, which are then handed over for further optimisation along other dimensions in another process. In this sequential approach every upstream process will limit the degrees of freedom in optimisation of the processes following. Ideally, all these processes should be run as one single process so that the global optimum can be found (as opposed to local optima). Although, from an IT point of view, this still represents a long–term vision, there are some areas where simultaneous optimisation can work:

— Fleet assignment models work optimally in junction with schedule profitability models, with quick iterations among schedule and fleet — Fixing the schedule timing too rigidly can limit fleet assignment and rotation possibilities: working with "time windows" for the schedule (i.e., flight ABC to leave between 8:00 and 8:10) and fixing the times driven by optimal fleet assignment and aircraft rotation solution can save up to 1% of direct operating and spill costs, according to simulations performed by MIT, GERAD and a major US airline

— Integrating fleet assignment with crew rotation planning can provide benefits of about 3% of total operating, spill and crew costs, according to tests by MIT and a major US airline — Integrating maintenance planning, aircraft routing and through assignment can also lead to cost savings

Most of these systems are still in the test phase, but it probably will not be long before they are used, with quite significant impact on the overall process. This implies that the network planning and scheduling process will have to be linked much more strongly to resource planning and optimisation processes, with clear synchronisation points, full data compatibility and simultaneous optimisation.

Production re-optimisation process

Increasing volatility of demand and a trend towards shorter–term booking behaviour are putting the traditional planning philosophy under pressure: to try to forecast demand 9–12 months in advance as accurately as possible and to expect minor deviations as execution approaches has some clear limits. A new planning paradigm is emerging, which essentially acknowledges the fact that planning uncertainty is high, and processes have to be designed to be flexible in the short term to adjust to real market demand.

This does not mean that production should not be optimised for each sub–season based on the best possible aggregated demand forecasts: this is and will remain important, as capacities are (still) needed to steer booking class availability in modern revenue management systems, so it is still important to be in the market (i.e., in the CRSs) early on with the best possible estimate of the right product (i.e., right capacity). On the other hand, airlines should be ready to re–optimise production on an ongoing basis (e.g., through capacity down or upgrades), as soon as deviations from the basic plan are detected. And this should be a very normal, standard process and not an operational nightmare!

Demand–Driven Dispatch or Dynamic Aircraft Reassignment are IT tools that can systematically screen for and execute aircraft swaps based on revenue management forecasts. Fleet commonality is a great enabler here, as some of the typical crew implications can be substantially reduced (in other words, cockpit and most cabin crews will still be flying to the assigned destination, but they will know the size of the aircraft only at the very last moment. Only a small number of flight attendants need to be flexible and need to fly to the destinations where the large planes are flying). Bottom–line benefits in the range of 1% of revenues can be expected, depending on variability in demand, but also on fleet mix: a balanced mix of smaller, medium and larger aircraft (e.g., A319, A320, A321) is required to be able to re–adjust capacities. If the fleet is composed of, say, 90% of A320 and only a small number of A319 and A321, even the best Demand–Driven Dispatch algorithm will not be able to capture benefits.

Reliability management process

Delays and cancellations are major causes of customer dissatisfaction, but also a significant cost block for airlines, both in terms of cash out (to pay hotels, re–bookings, etc.) and loss of future revenues due to loss of goodwill. Airlines reacted to last year’s major problems by launching task forces to fix the problem, which is now better under control. This might have been an overreaction, with reliability improvements achieved at very high cost, e.g. by adding a large number of aircraft as operational reserve and to "relax" aircraft rotations. Again, reliability management is a cross–functional (in this case even cross–company) process touching a dozen operational as well as planning processes. The objective of the process is to create the most economical level of punctuality by acting both on structural and on operational factors:

- Schedule structure and aircraft rotations, especially in a hub environment, have an impact on punctuality. But network planners do not have the tools to optimise them, nor do they normally care about what really happened when the schedule they planned was effectively flown (except for its profitability). If punctuality problems arise, the typical "easy way out" is to increase ground times across the board or other similar, non–specific or localised measures. Using simulation tools that can actually simulate flying a schedule and that use statistical and historical deviations from the plan, network planners can identify critical areas in their schedule where problems tend to accumulate (i.e., critical connections, or critical rotations). This insight would enable a better, targeted intervention into ground or block times and rotations, fixing the problem at a much lower cost.

- Operational factors are equally important.

During an aircraft turnaround dozens of processes run in parallel or sequentially: de–boarding, baggage unloading, cargo unloading, cabin cleaning, catering handling, refuelling, crew changes, cargo loading, baggage loading, boarding, etc. The ability to monitor these processes in real time and to quickly spot problems can significantly reduce reaction times. Even more important, during the day an Operations Control Centre will already know exactly how much delay has been accumulated in which part of the network and what kind of external factors might have a further influence. From this information an airline should be able to forecast, a few hours in advance, how critical the next wave in the hub is likely to be, so that the necessary actions can be taken (e.g., dispatch more people to the transfer desk or to the gates, identify the most critical connections and set priorities for the ground handling staff, etc.). And this task is non–obvious, as its implies strong cross–company collaboration, which must be laid out in the Service Level Agreements, and include IT integration, providing real–time event notification and display.

CRM process

Understanding among industry players about what CRM really is and does can be quite divergent; unfortunately, in many cases is understood as just an IT issue. While IT can play a key enabling role, CRM is first and foremost a cross functional process. Pulling all possible customer data into a data warehouse and running data mining programs will not make the difference, it is only a piece of the puzzle. Even if the data are effectively used to run targeted campaigns based on behaviour, potential and permission of customers, this taps only into one part of the total potential.

A more comprehensive view of CRM should include the management of the multiple contact points with a customer during his full experience, before and during the booking process, during and after the travel execution. There are a large number of actions and decisions that need to be taken by front–line staff in different functions at different contact points, and many different ways to tailor the customer interface of electronic channels

Implications for senior managers

Getting better in cross–functional management could become a competitive advantage and significantly contribute to the bottom–line (although it must be clear that this is not a substitute of a sound strategy, and of good cost and market positions). However, if the basis is sound, moving along this path might require some more fundamental thinking on some issues:

- How should the business system be configured? Which processes exist, what is the underlying planning and optimisation philosophy, and what flexibility is embedded in the processes?

- How should the appropriate organisational behaviour be fostered in order to reward cross functional collaboration without compromising on functional excellence?

- What kind of information would be needed to get the required transparency to efficiently support the processes and key decisions (e.g., key performance indicators, visibility of trade–offs, etc.)?

- How should the key management processes support the right decision making, and what is the appropriate organisational level to take what type of decision?