Virgin's airlines: What's real, what's hype?

Jul/Aug 2001

Virgin Atlantic enjoys a generally favourable high–profile in the British popular press; the other Virgin aviation interests receive a great deal of coverage as well. But what is the reality of Sir Richard Branson’s aviation empire?

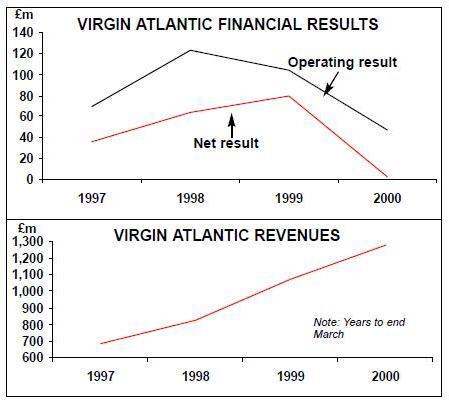

The latest available accounts for Virgin Atlantic Ltd — the airline plus Virgin Holidays (a tour operator) and Virgin Aviation Services (a freight handler) — are for the year to April 2000. These represent the legal minimum information required in the UK. Figures for the year to April 2001 will not be available until late this year.

Turnover was 19% up on 1998/99 at £1.27bn but operating profit dropped by 55% to £47m from £104m. Then the company took an exceptional charge of £41m relating to "payments to staff and certain directors…. as a consequence of the investment by Singapore Airlines". The highest paid director, presumably Sir Richard, received payments of £3.5m in this year.

As a result of the exceptional charge, pre–tax profit for Virgin Atlantic plummeted to £4.1m from £98.7m in the previous year.

However, Virgin Atlantic’s balance sheet improved from 1999, when there were negative shareholders' funds of £9m, to a positive balance of £105m. This was due to the injection of £100m of additional capital, in the form of preference shares, £49m from SIA and £51m from Virgin itself. However, Virgin Atlantic’s balance sheet is still heavily leveraged with a net debt/equity ratio of about 80:20. For comparison, its 49% shareholder SIA has a net asset value of some S$12bn (£4.6bn).

SIA paid £550m for its 49% stake in Virgin Atlantic (excluding the £49m capital injection), which would indicate a generous p/e ratio of 28/1 (after stripping out the exceptional cost). SIA’s interest in Virgin Atlantic is, however, not so much in its recent performance as about the future value of its Heathrow slots, especially the transatlantic ones.

There is no official indication from Virgin as to the airline’s financial performance for the 2000/01 year. However, unofficially, a result better than the pre–extraordinary £45m of 1999/2000 is mooted. If so, the result will have been achieved in adverse trading conditions.

First, the surge in fuel prices must have had a sharp impact on a fleet that contained 11 747–200s with an average age of 23 years.

Second, Virgin Atlantic remains very heavily exposed to the North Atlantic, despite the investment in new routes. Overcapacity started to emerge in this market in 2000 and the supply/demand balance has deteriorated this year, and business class yields have come under intense downward pressure. In the year to April 2000, 68% of Virgin Atlantic’s sales were made in the UK and a further 26% were made in North America.

Third, Virgin has launched a series of new services which will probably have not matured to profitability yet. These include Shanghai, Delhi, Capetown and Las Vegas, and the Johannesburg service will have been which have impacted by local difficulties. The Indian routes, operated under a code–share agreement with Air India, are apparently suffering from Indian government interference on fares.

At the inauguration of Virgin’s Toronto service in June, Sir Richard conceded that the strength of the competition — not just from Air Canada and BA but also from Canadian charter carriers operating into the same London airport, Gatwick, as Virgin — would mean that the carrier might not break even for two or three years.

The value of the brand

However, Sir Richard insisted that great advantages would accrue to the Virgin Group from the introduction of the Virgin brand to the Canadian market. The brand is central to Sir Richard’s business thinking. He is dismissive of conventional financial analysts who fail to recognise that his balance sheets contain hidden brand assets; this was the stated cause of his rapid disillusionment with the stock–market when Virgin was listed briefly in the late 80s.

The brand can be leveraged in various ways. It is a way of drawing in capital and technical expertise which then can be branded into, for example, Virgin Mobile, Virgin Cola, Virgin One (financial services), with the Virgin Group taking disproportionately high shares in comparison to its capital input. The brand also has in the past enhanced asset values when, notably, Virgin Music was sold to EMI at a hefty premium in order to provide desperately needed funds for other parts of the empire. In the UK the Virgin sign is ubiquitous. But it is interesting to note that the Virgin brand can be maintained after Sir Richard has sold out all his interests — examples are Virgin Radio and Virgin Sun.

The problem with brands is that you have to believe in them: value takes a long time to create but can dissipate very quickly. Unfortunately, Virgin’s brand in the UK (and it is still essentially a British rather than a global brand) has been devalued in recent times. Attaching the Virgin name to mobile phones or soft drinks has added nothing to the basic product, and consumers know this. More worryingly, the foray into the train sector has not been a success: the product is mediocre, passengers have been incandescent about the on time performance (admittedly much of which is the fault of the rail infrastructure), and politicians, previously supportive of Virgin, have been disillusioned.

Under the leadership of MD Steve Ridgway, and previously Syd Pennington, Virgin Atlantic’s own particular brand has remained impressive, and the airline continues to win travel trade and passenger awards (OAG Airline of the year 2001). But Virgin Express’s market perception is very poor. The collateral damage for Virgin Atlantic has been limited, but the opportunity of introducing a new market of continental European travellers to Virgin’s long–haul services has been lost. And there is little real synergy between Virgin Atlantic and the other Virgin enterprises — Virgin Megastores, for example, do not sell airline tickets.

Then there is the issue of Sir Richard himself, so closely identified with his empire and Virgin Atlantic in particular. There are two viewpoints: one, he is a charismatic, anti–establishment, amusing, dynamic entrepreneur; two, he is a manipulative, evasive exhibitionist. Neither version of course fully describes his complex character, but it is fair to say that the positive image he projected up to a couple of years ago has been deflated recently, notably by an unflattering biography by Tom Bower.

Virgin Atlantic’s uniqeness

Virgin Atlantic is unique in that it is a European long–haul carrier without national flag–carrier status. It projects a dual image: of being a low–cost carrier and being a very upmarket business airline. The bargain image traces back to its start–up in 1984 when it offered £99 return fares to New York, but its profits have been built on its business class product, following the move of this flight from Gatwick to Heathrow in 1991. The Upper Class product genuinely did revolutionise business travel, offering space akin to First Class, a lounge bar, attentive but informal service, ice cream with the movies, shiatsu massage and so on. On the ground Virgin’s limousine service and the Virgin Clubhouse at Heathrow were vastly superior to anything provided by the competition.

Service competition since then has intensified, with BA’s flatbeds now representing the ultimate in business class comfort. Virgin has responded by installing its own fully reclining seats on aircraft operating to New York, San Francisco and Chicago. Another Virgin innovation — Mid–Class, a spacious economy seat introduced in 1994 — has now been emulated by BA with its super–economy product.

Virgin Atlantic’s route development sought to duplicate the success of the New York route by targeting BA’s most profitable long–haul services — Tokyo, Hong Kong, Johannesburg, for example. Lagos in Nigeria was inaugurated in July, a route that desperately needs more business–class capacity, in fact just more capacity. It has also expanded rapidly on leisure–orientated services like Miami and the Caribbean. The leisure services are generally operated out of Gatwick while business or mixed flights go from Heathrow.

As a non–flag–carrier Virgin Atlantic has not only to battle the competition but also the bilateral system. This involves a lot of polemics and an overlong anti–BA campaign based on accusations of dirty tricks back in the early 90s (it is often forgotten that the law suit claiming treble damages against BA was dismissed by the US courts).

In negotiating for international rights and arguing its aeropolitical case Virgin Atlantic is usually vociferous and quite effective. Barry Humphries, a highly–rated airline economist and bilateral negotiator, was brought into the airline by Sir Richard from the UK CAA in 1996.

However, the UK–US "open skies" negotiations pose a particular challenge for Virgin. On the one hand, it has declared itself time and time again to be a strong proponent of deregulation and free markets; on the other, the prospect of any opening up of Heathrow to other US majors is horrifying given that LHR–JFK, where it has a 25% share, is by some way its most profitable route. So it virulently opposes the BA/AA alliance, overtly of the grounds of the anticompetitive effects of such a link–up, but also because of its natural desire to preserve its market share. In reality it has usually taken a similar lobbying position to BA in Bermuda 2 talks.

In PR terms Virgin’s message is persuasive: Sir Richard says he wants genuine deregulation, which means domestic cabotage rights for European carriers in the US, right of investment in US domestic carriers and an end to the Fly America programme. Whether or not Virgin is really interested in operating in the US domestic market (probably not as it had a chance to get into the JetBlue project, which it seems to have turned down) is irrelevant; what is important is that Virgin can rely on the US negotiators to reject these conditions on principle, and hence postpone the introduction of the USUK open skies.

Disconcertingly for Virgin, BA now looks as it may accept "open skies" and LHR slot give–ups in return for approval for the BA/AA alliance. Sir Richard’s response is to announce that he has decided that the EC should be negotiating such agreements in the context of the TCAA.

Virgin has dallied with the idea of expanding into medium haul services. Two years ago it applied for the London–Moscow licence in competition with British Midland, but was rejected partly because it did not have suitable equipment available. Its A321 service, London Heathrow- Athens, is looking like more of an anomaly with the rapid growth of easyJet’s low–cost London Luton- Athens service on this very price–sensitive route. When or if Olympic is restructured with the aid of an airline investor this route could be rationalised, with the Greek airline operating the European sector and feeding long–haul passengers to Virgin Atlantic. Virgin Atlantic is a minor partner in the Axon consortium which has been recommended by CSFB to the Greek government as the preferred investor in Olympic.

The Virgin Express disaster

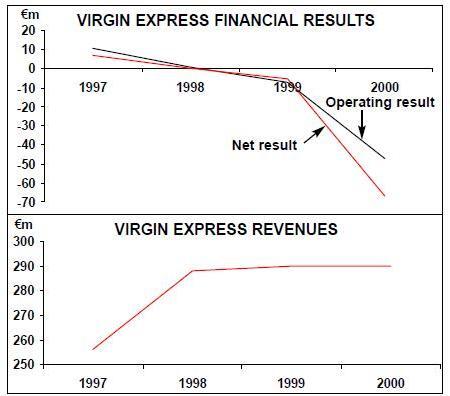

Virgin Express was set up in 1996 and 41% of the company was floated the following year, the only part of the Virgin empire that is stock–market listed. In contrast to Ryanair and easyJet, its low cost rivals, the share performance has been disastrous — launched at €17, the share now languishes at around €1.

The strategy was deeply flawed. Basing the carrier at Brussels meant that the airline was locked into high labour costs and inflexible work rules. The main route was to London Heathrow with Virgin Express operating as a sort of franchisee for Sabena whose LHR slots were in effect leased to Virgin. The product was at best confused — Sabena sold and managed the business class seats on the 737s while Virgin was in charge of the back of the aircraft — at worst unreliable and of poor quality. An attempt was made to schedule the flight to connect with Virgin Atlantic but little connecting traffic was achieved. Part of the operation was shifted to Ireland, put up for sale then closed down. The fleet has been halved to 11 units and deliveries from Gecas deferred, probably permanently.

Despite reporting a net loss of €65m for 2000, the company officially remains optimistic about breaking–even this year. In reality though, it is unlikely that the Virgin Express/Sabena agreement on Brussels- Heathrow will survive the rescue plan for the Belgian flag–carrier, leaving Virgin Express operating from Zaventem competing with Ryanair operating from Charleroi — an unequal struggle.

Perhaps Virgin Blue in Australia will do better than Virgin Express (or Virgin Sun, a tour operator/charter carrier, which was sold off to First Choice early this year). Virgin Blue has produced a marginal operating profit in the first seven months of its operation, but the net loss since its incorporation to the end of March 2001 come to A$11m (US$7m). Australian observers point out that this period excludes the really vicious fare wars that took place in the Australian market culminating in the demise of Impulse. Virgin Blue will probably end up in some form of anti–Qantas alliance with Ansett.

Inevitably, Sir Richard has promoted the idea of Virgin entering the Corporate Jet market, following in the wake of BA, United and Delta, with a new venture named Virgin JetSet. So far though this amounts to a meeting with Bombardier about future orders for the 19–seat Global Express jet.

The future

So what is Virgin’s future in the aviation industry?

Virgin Express looks very sickly, but its assets might be transferred to Australia where Virgin Blue will probably ally with Ansett (and SIA). New ventures such as Virgin Canada, an idea floated by Sir Richard, are probably non–starters.

As for Virgin Atlantic, much depends on what is happening in the other parts of the complex and opaque Virgin financial web of offshore companies and family trusts. According to analyses in The Economist and elsewhere, Virgin Atlantic has in recent years acted as a cash–cow for other parts of the Virgin empire (and its fleets has regularly been used as collateral for loans for other Virgin businesses). Almost all the SIA cash went to stave off a financial crisis in the megastores.

If another urgent need for cash emerges, the sale of the remaining 51% of Virgin Atlantic to UK–based interests amicable to SIA is a possibility (SIA’s chief executive Dr C.K. Cheong and two other SIA directors sit on the 10–man board of Virgin Atlantic). Then SIA would have achieved its aim of winning transatlantic flying rights. It would also become the most important Star member at Heathrow ahead of Lufthansa and bmi.

Finally, it is also worth considering Virgin Atlantic’s capital commitments. Its orderbook now consists of three 747–400s (in addition to two just delivered), 10 A340–600s (plus 8 options) and six A380s (plus six options). The total value of the orderbook therefore works out at somewhere between $3bn and $5bn (depending on whether the options are taken). In addition, rumours are circulating about Virgin’s strong interest in Boeing’s Sonic Cruiser.

In its early days Virgin Atlantic’s success was built on leasing fairly elderly 747s and refurbishing them so well that the passengers thought they were new. But today the fact is that a company with a book net worth of about $140m and last reported net profits of $6m has a potential capital commitment of $5bn or maybe more. Conventional financial analysts would be raising their eyebrows.

| LHR | LGW |

| Newark | Boston |

| JFK | Orlando |

| Los Angeles | Newark |

| San Francisco | Barbados |

| Washington | St. Lucia |

| Chicago | Antigua |

| Johannesburg | Toronto |

| Capetown | |

| Tokyo | |

| Hong Kong | |

| San Francisco | |

| Shanghai | |

| Delhi | |

| Athens | |

| Lagos |

| Current fleet | Orders | (options) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 747-200B | 11 | - | |

| 747-400 | 10 | 3 | |

| A321 | 1 | - | |

| A340 | 10 | 10 | (8) |

| A380 | - | 6 | (6) |

| TOTAL | 32 | 19 | (14) |