The future for air cargo

Jul/Aug 2001

The establishment of separate cargo subsidiaries, greater cooperation with alliances, vertical integration with forwarders and a relocation of cargo operations to secondary airports — these are the key trends in the air cargo business identified by DVB*.

Closer links will develop between the members of air cargo alliances as the trend towards the formation of independent air cargo companies, achieved through a hive off of cargo operations, gathers momentum. Lufthansa has created Lufthansa Cargo and has announced plans to acquire a 49% share stake in SAS Cargo. Iberia has also stated its intention to form an independent air cargo company. JAL plans to establish a separate company but only for the purpose of marketing freight capacity. Northwest has formed NWA Cargo which will be responsible for freighter operations and the marketing of the belly holds of NWA’s passenger aircraft. Singapore Airlines Cargo gained its own AOC earlier this year.

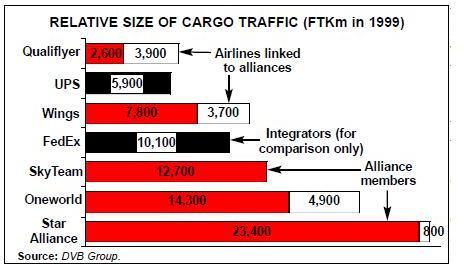

It is interesting to calculate the scale of the role alliances could play in air cargo transportation if all member airlines co–operated closely. Close on 57 % of total FTKT is already produced by member airlines of the five alliances (including Qualiflyer) and airlines linked to these alliances. Star enjoys the most significant potential, oneworld ranks second followed by SkyTeam and Wings.

An increasing number of passenger airlines will decide to market their overall cargo capacity to another airline rather than to customers on their own account. By selling capacity to a cargo–focused passenger airline or — even better — to a combination airline, handling and marketing costs can be saved. The attraction to the buying airline lies in the advantages of a broader network and the prospect of achieving handling and marketing cost savings.

The forwarders

In global terms even the largest freight forwarders hold no more than small market shares, although they account for considerable shares of their home markets. Recent years have seen an increase in merger activity, hence an increase in concentration. This trend will continue, the latest development among large forwarders being cross–continent co–operation. Some large forwarders have been acquired by integrators in the latter’s quest to increase product portfolios.

What, therefore, does the future hold for small and medium–sized freight forwarders? Such firms are currently confronted with the creation, through M &A activity, of large/global players with the international capabilities that airline partnership programmes will favour. The choice that small and medium sized companies face is to specialise in niche markets or co–operate with their peer group. In Germany, air cargo forwarders have started to co–operate in joint ventures such as "Challenge," "Future" and "Iglu". Such co–operation can pave the way for significant expansion, particularly if the participants utilise common production standards and a joint brand–name.

Airline/ forwarder relationship

Some of the major airlines have, in the past, attempted to approach shippers directly. Freight forwarders, unsurprisingly, have viewed this development with concern. Airlines believed that the freight forwarders, capitalising on the bargaining power derived from consolidation, have succeeded in passing on most of the downward pressure on revenues. Certain airlines have established closer relationships with the shippers by setting up key account management and/or logistics management operations.

A major problem for the airlines, however, is that their experience in organising pickup, delivery and other services related to air cargo transportation is, for the most part, distinctly limited. A few airlines have gone so far as to acquire stakes in freight forwarding companies. In the event, the debate about the airlines' direct sales approach has cooled as a result of closer co–operation between the warring parties through partnership programmes.

Lufthansa Cargo has launched the Business Partnership Programme designed to incentivise freight forwarders that contract substantial airfreight volumes with the airline. With the advent of partnership programmes, airlines and forwarders could conceivably agree to approach shippers jointly, particularly when shippers require global logistics solutions.

Some air cargo forwarders have taken steps towards vertical integration; examples are Emery Worldwide and BAX Global. Panalpina, Eagle Global Logistics (EGL) and Danzas have all commenced their own dedicated freighter services on international routes.

In the wake of the creation of a few air cargo alliances in the airline industry and a few global forwarders, the forging of strong vertical links between airline alliances and freight forwarders appears inevitable. Lufthansa Cargo is already closely linked to Deutsche Post World Net which has acquired various forwarding companies including Danzas (Switzerland), ASG (Sweden) and AEI Air Express International (USA). Deutsche Post World Net is also the majority shareholder in DHL International.

Integrators

By expanding into heavier consignments and offering value–added services (i.e. logistics), the integrators have started to attack freight forwarders in their traditional field. Such developments have been largely shrugged aside by freight forwarders who have taken the view that the international transportation of heavy consignments requires considerable expertise in respect of customs clearance procedures. The forwarders have also argued that because consignments vary so much in size and weight it is difficult to achieve economies of scale in terms of trans–shipment activities. Forwarders should be concerned, however, because integrators such as UPS and FedEx clearly harbour ambitions to become global players in the heavy cargo business.

UPS recently acquired Fritz Companies, a large US–based forwarder, and last year acquired Challenge Air, a major air cargo carrier that serves the Latin American market. Nor should it be forgotten that the integrators are more advanced in the use of EDI technologies for the management and control of shipment flows then most forwarders. Last year FedEx acquired American Freightways, a prominent player in the LTL trucking business. With the benefit of other acquisitions, FedEx has now built up a strong ground handling system for heavy cargo in the US.

An interesting development in the wake of the deregulation of many countries' postal markets is that former postal administrations have been transformed into management–led companies with ambitious designs to recapture the market shares lost to integrators' parcel services. Canada Post Corporation was ahead of this development when it acquired Purolator Courier System. Dutch Post acquired TNT Worldwide Express and now operates under the name TPG (TNT Post Group) while German Post has acquired a majority stake in DHL International. Both companies are intent on achieving global market status. German Post, having also acquired some major forwarder enterprises, currently represents a much more serious rival to UPS and FedEx than TNT Post Group. German Post also enjoys a good working relationship with Lufthansa Cargo.

The integrators, all of which use airline capacity, are important customers for many airlines, so much so that some airlines and integrators have concluded blocked space agreements. Under such agreements cargo capacity on freighters is shared between the partners of the agreement.

Another interesting development is the co–operation between FedEx and the US Postal Service. FedEx will provide the airport- to–airport movement of containers holding USPS priory and first–class mail from August 2001. In return, FedEx can install more than 10,000 drop–boxes at post offices in 120 US metropolitan areas.

Airports

Competition for air cargo among European airlines in home markets is intense; witness the rivalry between Air France and Lufthansa Cargo. Air cargo that originates in Germany is trucked by Air France to Paris for onward carriage, while Lufthansa Cargo offers trucking connections to Frankfurt for air cargo that originates in France. One reason for this is that passenger airlines have reduced their cargo capacity through offering greater flight frequency with smaller aircraft. Nor do all cargo consignments fit into the holds of passenger aircraft.

Air France has also opened a trucking terminal at Hahn airport, a former USAF airbase outside Frankfurt, which has been successfully converted into a commercial airport. Air cargo shipments originating in Germany are collected and consolidated in Hahn and then trucked to Paris for onward transportation. Railways can be utilised for feeder services but this is only a practical alternative if direct rail access to the airport’s cargo area is available and the price is competitive in comparison with trucking.

Passenger hub airports still predominate in the cargo business, but problems for airlines operating freighters into these airports lie ahead. Night curfew restrictions already exist, and there is mounting demand for a complete ban on night–time operations. The controversy over plans to increase the capacity of Frankfurt/Main’s international airport is a sign of the times. In the event, the government of Hessen has agreed on a compromise born of a mediation process which, in essence, stipulates that a new landing strip will be built, the $1 being a ban on aircraft operations during the night. Unsurprisingly, charter airlines and the air cargo industry are opposing this decision.

Integrators, which are not dependent on passenger aircraft movements, have tended to concentrate on remote airports where no night curfew restrictions exist. That is not to say that the integrators have escaped completely. TNT has moved from Cologne to Liège, Belgium, while DHL has been confronted with the Belgian Government’s plans to limit night–time aircraft movements at Brussels airport which serves as DHL’s main European hub. With more and more of Europe’s former military air–ports being converted for commercial use, alternatives would appear to be in sight.

In Germany, airports such as Hahn, Lahr, Parchim, Laarbruch and some others are striving to attract air cargo business. In France, Chateauroux and Vatry fall into the same category. In Belgium, Ostende and Liège have succeeded in wooing business from air cargo operators. There is little chance, however, that all these airports will develop into important air cargo centres. The need to operate aircraft at any time of the day or night (24–hour airport access) is vital but is by no means the only facility required by air cargo operators.

Such airports also need adequate space for ground handling facilities, excellent access to highway/railway systems, an adequately sized and skilled labour force and a high degree of reliability in respect of weather conditions and air traffic control. They also need adequate runway systems to facilitate large freighters will fill loads. Ideally, a cargo airport should be situated relatively close to one of the major economic regions where the scale of inbound and outbound traffic serves to make hub operations more attractive.

There are several reasons why major combination airlines, irrespective of the night noise restrictions, should consider splitting freighter and passenger aircraft operations. Air cargo traffic can be expected to triple over the next 20 years, and this growth in itself should pave the way for a separation of freighter and passenger aircraft operations.

The combination airlines concentrate have to on maximising passenger load factors, and so air cargo capacity will therefore remains tight on many routes, a factor that will be exacerbated by any further restrictions on cabin baggage size. Even now, cargo shipments are occasionally left behind when passenger figures exceed the forecast.

Differentiation of air cargo services also lends itself to a split between freighter and passenger aircraft operations. Many combination airlines already offer time–definite services in respect of air cargo shipments. These services usually cover express cargo, standard air cargo and special cargo such as horses, perishables and out–sized cargo. Combination airlines could choose to confine passenger aircraft cargo to express shipments which would be subject to quick ground handling at the hub airport.

What has become apparent is that airports dedicated to freighter movement and air cargo handling are set to play an increasingly important role in the air cargo transport industry. If Europe’s major international airports impose a ban on aircraft operations during the night, combination airlines will have to consider reducing or even giving up their air cargo activities. Another option is to reschedule freighter movements to those airports that offer 24–hour access. Combination airlines might choose to switch certain freighter operations from night to day, particularly if airport capacity during the day is increased, but it will not be possible to switch all freighters because the industry’s logistics systems are often based on overnight transportation. There are pros and cons to a switch of freighter movements from combination airports to pure air cargo airports.

One of the disadvantages relates to the investment that would be required in new air cargo facilities. Meanwhile, existing facilities would become obsolete. Another disadvantage is that a second road feeder service would need to be established. On the other hand, the alternative airports may choose to levy very attractive airport charges.