EADS: a case of Euro-over-complexity

August 2000

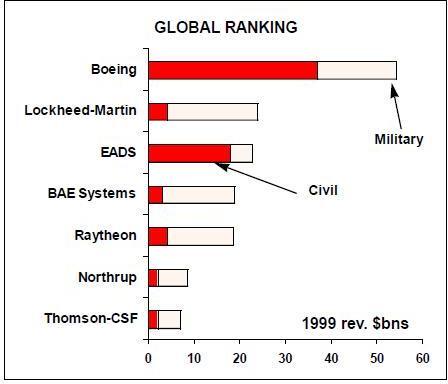

On July 10th the single entity that encompasses most of the European aerospace industry came into being, with the launch of European Aeronautics Defence and Space (EADS), a $22bn revenue company, with 96,000 employees and world–leading positions in markets such as jet airliners, helicopters and satellite launchers. It is number three in the world aerospace and defence league behind only Boeing and Lockheed Martin, and aims rapidly to overtake Lockheed.

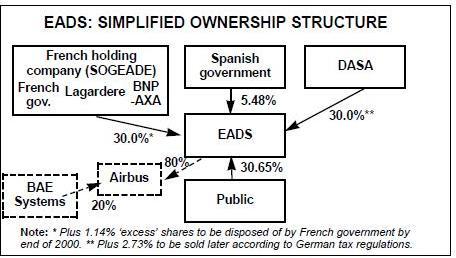

The English acronym EADS sounds awkward, but unfortunately it accurately reflects the awkward and unwieldy structure of the new European venture. The share–ownership formed through the union of DASA (the aerospace part of DaimlerChrysler) and Aerospatiale Matra (with a dash of Spain’s CASA bought up and folded in by DASA) is overly complicated (see chart), largely because of the need to satisfy certain French government interests.

The corporate governance is worse, flowing as it does from the political need to keep a head office in Munich and another in Paris. National governments, frequently being asked to supply civil aircraft subsidies and opportuned to indulge in big military aerospace orders, demand local head offices.

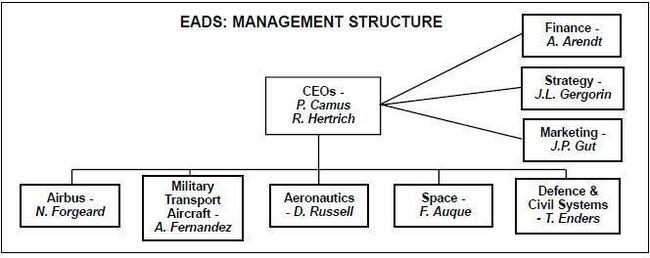

The management structure of EADS reflects all this politicking: two chairman, two chief executives, and so on. A real merger would have thrown everything in the air, opened the top jobs to competition across the talent from the companies coming together and genuinely tried to forge a new European enterprise rather than one that, its formidable capabilities notwithstanding, has its hands tied behind its back when it comes to rationalising its operations and organising itself to deliver maximum shareholder value.

Nevertheless, the CEOs, Philippe Camus and Rainer Hertrich, are both polished and reasonable people, well aware of the political and business minefield in which they are working. The pair have devised a rough–and ready way of dividing up the people who report directly to them: Germans report to the Frenchman and non–Germans report to Hertrich. They claim that they can handle joint responsibility because they speak to each other on the video phone every day, and rely on utter frankness and no hidden agendas to resolve differences. Both are ensconced for five years, as things stand at present.

EADS has several divisions: Airbus; Military transport (really another new part of Airbus); Aeronautics (that means military aircraft and helicopters); Space; Defence and Civil Systems (which includes missiles, defence electronics, some telecoms and some services). An impression of the complexity can be gained from the fact that there are no fewer than three missiles companies in this structure.

So, apart from an over–complicated European company, what is EADS and where is it going? Before counting in the huge $17bn order for the A300M military transport outlined at the Farnborough Air Show, it is 54% Airbus (which will become the Airbus Integrated Company, 80% owned by EADS and 20% by BAE), 18% military aircraft and helicopters, 16% defence and civil systems (that means electronics and missiles), 11% space (which means satellites and launcher systems).

A problem is that many of these programmes are themselves joint ventures, mainly with BAE Systems. The potential for conflicts of interest, clashes of objectives, political realities and simple unmanageability across EADS is enormous. The spread of shareholders from German private company to French government is guaranteed to produce tension.

Still, EADS has one clear strategic aim. It wants to overtake Lockheed Martin to become the number two defence and aerospace company worldwide behind Boeing. It boasts of being number two in civil jets (behind Boeing) and missile systems (behind Raytheon); number one in helicopters and in satellites launchers; number three in satellites. But it comes a poor fourth in military aircraft, despite the Eurofighter orders being placed by European governments.

Camus and Hertrich talk about more than 400 integration projects and their aim of industrial integration within two years. There are McKinsey consultants on hand to tell them when managers are disagreeing because of cultural differences or because of substantive differences. There will be no shortage of training seminars and top managerial meetings.

The subsidiarity principle

But the guiding principle of management in this grand new European enterprise is summed up by one word: “subsidiarity”, the EU principle that decisions on integrations and harmonisation should be taken at the low set possible level . Expect, therefore, the integration of EADS to be about as simple and straightforward as the construction of an integrated European Union.

None of this would matter all that much if EADS had the potential to evolve its various components into an ideal whole, worth more than the parts. Its structure may prevent that ever happening. The ideal structure would have been for DASA and BAE to have merged and then folded in the French later (along with Italy’s Finmeccanica and CASA). That, at least, would have brought together the main Eurofighter partners and created a solid base for Airbus. But BAE rather arrogantly assumed it could strengthen itself by absorbing Marconi Defence Systems (part of GEC) before going on to merge with the Germans. DASA would have none of this and chose to link up with Aerospatiale to form EADS.

Apart from the politically imposed complexity of its ownership and management structure, EADS is left with other weaknesses, including the following.

- A basic imbalance of its business, depending so heavily on Airbus;

- The lowly position it enjoys in fighter aircraft;

- Its incompleteness, without a strong position in defence electronics;

- Its dependence for more than two–thirds of its turnover on joint ventures with BAE Systems, for example, in missiles.

- The barriers to forming links with US aero–space companies, given the reluctance of the American government to share technology with non–British European businesses.

EADS aims to move from a pre–tax margin of 6.4% last year (on a pro forma basis) to one of 8% by 2004; it would have been 10% but EADS will be expensing the development costs of the Airbus A3XX during this period. The decision not to capitalise that investment means it will pay back faster if sufficient aircraft are sold at reasonable prices, as the programme develops.

Break–even for the A3XX is some 230 units, but EADS expects it to repay its investment with a handsome return when it sells 780 aircraft; the company thinks it can win two thirds of the market for aircraft over 400 seats, because its offering will be superior to the upgraded 747X that Boeing will offer in competition. This ignores the fact that Boeing could have its futuristic blended wing body aircraft (currently on its second scale model) on the market halfway through the life of the A3XX. This revolutionary aircraft- virtually a flying wing–is being designed in three versions carrying 250, 450 and 650 seats. Boeing reckons it could be on the market inside ten years, with aerodynamics and operating costs that would revolutionise the industry.

Back on earth, EADS reckons about half of the synergy to improve its margin is expected to come from joint purchasing, with a further third to come from internal reduction in costs base in areas such as R and D and production. Finally, 15% is expected from boosting sales, because collectively EADS should win business that separately the partners could not.

Delivering synergies

Again the key question: can this amalgam actually be bashed into shape to deliver some these synergies? The main obstacles to that is going to be resistance in France to rationalisation that would lead to job losses in what is seen as a strategic industry. The presence of the French government as a 15% direct shareholder militates against any effective action on that front.

Then there is the fact that EADS is heavily dependent on BAE Systems for many of its programmes. And BAE is way ahead in terms of establishing itself as a transatlantic aerospace and defence company. Although BAE’s chairman Sir Richard Evans rules out any merger with Boeing, it is clear that the two companies can only get closer, through joint ventures such as on the American Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) programme. There is no love lost between BAE and, in particular, the German component of EADS.

Too negative?

This review may seem unduly negative, but the history of aerospace mergers in the more straightforward US market is not very encouraging. Lockheed Martin never really got to grips with integrating the various businesses it brought together, and customers and projects suffered as a result. Raytheon attempted a full integration while keeping a customer focus, but still lost the plot. The jury is still out on Boeing/McDonnell Douglas. In Europe, with its fragmented national defence markets, only slowly being integrated with orders such as the Meteor missile and the A400M military transport aircraft, everything is infinitely more complex.