Northwest looks to the future after labour woes end

August 1999

Northwest has just returned to profitability after last year’s work slowdowns and debilitating pilots’ strike. Are its labour troubles now over and has business traffic returned? What are the prospects for Asia and global alliance–building?

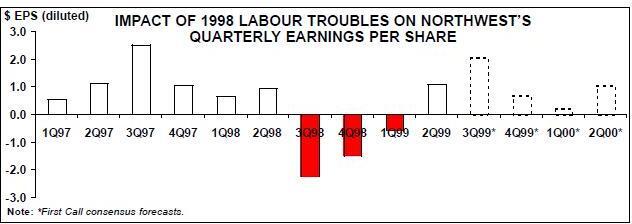

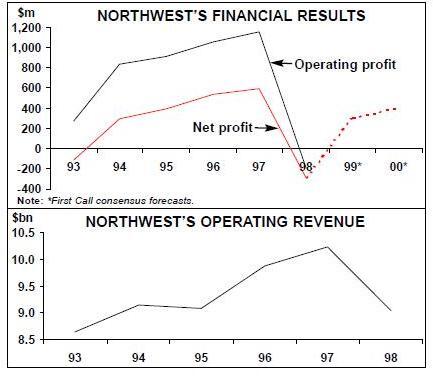

While most of its competitors reported reduced earnings for the quarter ended June 30, Northwest had reason to celebrate. It posted a net profit of $120m, breaking a three–quarter string of losses totalling $434m. Although the latest result represented just 4.6% of revenues, it was more than double the earnings in the same period last year, when work slowdowns by pilots and machinists first began to affect the company’s bottom line.

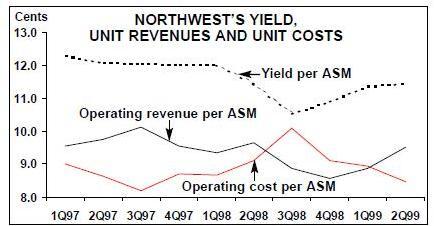

After its turnaround in 1994 and up to and including 1997, Northwest was one of the US industry’s best profit–performers. This was in large part thanks to an $886m three–year package of wage concessions secured in 1993, as well as extensive route and debt restructuring, which enabled unit costs to be lowered.

But the labour honeymoon came to an end in the second half of 1996, when the wages of Northwest’s workers snapped back to the August 1993 pre–concession levels. The net impact of that on the profit and loss account was actually not that detrimental, because the company was able to stop issuing common and preferred stock to employees (a practice that had been recorded as huge non–cash operating cost items).

But the subsequent inability to secure new contracts with the unions led to labour actions and a strike that cost the company well over $1bn in lost revenue and increased expenses in the 12 months to the end of March 1999.

The unions had been pressing for sizeable pay increases — after all, their pay was still at 1992 levels. They had become increasingly agitated about the management’s insistence on work–rule changes and productivity improvements and, in the end, lost patience at the lack of progress in the negotiations.

The troubles began with work slowdowns by mechanics in the spring of 1998, which cost an estimated $100m on a pretax basis in the second quarter of last year. The 18–day shutdown of operations due to the pilots’ strike in September and the preceding 30–day cooling–off period caused $630m of financial damage in the third quarter. Another $90m of negative effects were recorded in the post–strike recovery period in October–December. As a result, Northwest reported a $286m net loss for 1998, down from a profit of $583m in the previous year.

The impact on 1998 earnings had, of course, been fully anticipated by Northwest’s management and the financial community. But then came the unpleasant realisation that while leisure traffic had bounced back quickly with the help of fare sales, business traffic remained sluggish to return.

This reflected continued poor customer perception, not helped by a deterioration in service quality and on–time performance. Northwest reported another $29m net loss for the first quarter of this year, blaming $90m residual negative effects from the strike.

The June quarter results indicate that Northwest is at last well on its way to a full recovery from the strike. The company says that it has made “substantial progress” in recapturing its former share of business traffic, though yields and unit revenues have remained weak due to industry–wide domestic softness and continued troubles in Asia.

Significantly, in the latest period Northwest managed to reduce its unit costs to less than 8.5 cents per ASM from the 9–10 cents recorded in the previous four quarters. Cash reserves, which halved to $480m in the six months to December 31, had recovered to $618m by the end of June.

Are the labour troubles now over?

The strike was settled when Northwest and its pilots agreed on a new four–year contract, which represented a straightforward compromise on the pre–strike positions. In return for some productivity concessions, the pilots secured 3% annual pay rises, retroactive pay, stock options, a new profit–sharing programme, the phasing- out of a two–tier pay scale, furlough protection and restrictions on the use of regional jets by commuter partners. The deal was quickly ratified by union members.

As an indication of a new phase in management- pilot relations, in February this year agreement was reached quickly on pay rates on the A319, which was due to enter the fleet last month (July). To their credit, Northwest’s pilots have also cooperated fully on the implementation of domestic alliances. Pilot approval for the Continental alliance was secured well before the strike, and the new contract sealed things by granting the desired job protections.

But the pilots’ deal was only a starting point as contracts still had to be secured with five other large unions, and there was trouble brewing with two key groups. The IAMrepresented workers had already authorised a strike, while talks with the flight attendants, represented by Teamsters, had entered federal mediation.

Progress with the non–pilot groups has been mixed. On the positive side, dispatchers, represented by TWU, along with most of the small unions, settled fairly quickly. Also, the IAM strike threat dissipated as the National Mediation Board (NMB) declined to declare the talks at an impasse and IAM’s attention was diverted to fighting a challenge from a competing union.

The Aircraft Mechanics Fraternal Association (AMFA) subsequently won the right to represent Northwest’s mechanics, inspectors, cleaners and custodians (some 9,300 workers). The remaining 21,000 IAM members signed three new four–year contracts in February.

But the mechanics’ contract negotiations have been delayed by an NMB investigation of the AMFA election results, which were declared fair and valid only recently. This has meant that contract talks will not start till the autumn. It is hard to predict what kind of a negotiating stance the relatively little–known union will adopt.

AMFA’s position may, of course, be influenced by the outcome of the ratification vote for the June agreement with the flight attendants, which is at present scheduled for August 26. The tentative deal was significant in that it averted a very real threat of new labour disruptions at Northwest. In early June the flight attendants overwhelmingly approved a strike vote; although the NMB did not release them into the statutory “cooling–off” period that could have led to a full–blown strike, the Teamsters were planning to employ the highly disruptive “HAVOC” tactic of striking selected flights on a random and unannounced basis.

The problem now is that there appears to be considerable opposition to the deal among the rank and file, even though the final provisions are believed to have made Northwest’s flight attendants among the highest–paid in the industry and gone a long way in closing the gap in pensions and benefits. At this stage (late July) the general feeling is that the vote could go either way.

Quality, performance and image issues

The constant negotiations with so many unions have made it hard for Northwest to focus on repairing its service quality and image, which used to be impeccable before the 1998 labour troubles. However, recent efforts to improve operational performance have been successful. In June last year the carrier came worst in the DoT’s on–time performance and customer complaints rankings, and just six months ago it was still in the bottom half of the league. But in May (the latest month for which statistics are available) Northwest was second–best in both those criteria and had considerably improved its baggage handling reliability.

This has no doubt helped bring back business travellers, but that all–important segment is not likely to recover fully until all the labour contracts have been settled. It is totally inconceivable that Northwest’s management would allow another strike or even a near–strike situation to develop, but mere public protests by labour groups add to the image problem. Before tentative agreement was reached with the flight attendants, the workers picketed at airports against “corporate greed” and disrupted the company’s annual shareholder meeting to the extent that it had to be closed early.

But labour disruptions have not been responsible for all the damage. Northwest is still suffering the consequences of its response to a snowstorm that hit its Detroit hub in early January. A recent DoT report concluded that Northwest “jeopardised passengers’ well–being” by holding them in aircraft on the ground for up to eight hours without water, food or working toilets.

The carrier now faces a class action lawsuit from the stranded passengers alleging negligence, intentional infliction of emotional distress, false imprisonment and breach of contract. The debacle will go down in the history books also because it prompted legislative moves for a “passenger bill of rights” — now likely to be replaced by voluntary ATA–led reforms.

The DoT report criticised Northwest’s lack of emergency planning, poor internal communications, bad management of the crisis and senior management’s flippant comments in the aftermath — all hinting at a multitude of management problems at the carrier. In recent years Northwest has also been widely criticised for its poor treatment of the media (of which there was no evidence when the company was contacted by Aviation Strategy for the purposes of this article).

Occasional fines for maintenance violations are nothing unusual in the US industry, but Northwest is less able to afford the unfavourable publicity at present. Over the past eight months it has been fined several times for maintenance and security violations (the security company was replaced in March).

The snowstorm incident led to various changes in emergency procedures and planning. In order to be more responsive to its Detroit customers, Northwest assigned its executive VP customer service, Ray Vecci, to the additional newly–created position of president for Michigan operations.

The past year’s turmoil has led to extensive management changes. First, CFO Jim Lawrence was replaced with former CFO Mickey Foret, who was later also named president of Northwest Cargo. Marketing chief Michael Levine’s resignation in January was taken as an opportunity to strengthen international operations, marketing and sales with three new appointments or promotions. Northwest has also named new heads for planning, domestic revenues and information services, appointed a new VP for alliances and revamped its finance department.

Contrary to earlier speculation, John Dasburg, president and CEO since 1990, survived the pilots’ strike. In a well–timed move just two weeks before the January snowstorm, Dasburg signed a long–term contract to remain in that position. However, the appointment of Richard Anderson as Northwest’s first–ever COO will enable Dasburg to focus much more on the global alliance and other strategic issues.

A promising alliance position

Alliances are one bright spot that Northwest certainly intends to build on. Its longstanding relationship with KLM, which was the first–ever airline deal to secure antitrust immunity in the US and has been a commercial and financial success, is much more advanced in terms of the extent and depth of co–ordination than any of the other international alliances. The earlier equity link was never a happy one and it was severed two years ago, but Northwest describes the alliance as a “marriage for life”.

Consequently, the latest plans to expand the Wings alliance to integrate KLM’s partner Alitalia hold considerable promise. Alitalia formally joined the combine in May and an antitrust immunity application for a three–way global joint venture system was filed with the DoT. Under a precedent set by past deals, approval seems certain once Italy signs an open skies ASA with the US, which is expected to be in the near future (following provisional agreement reached in November).

The ending of the pilot strike enabled Northwest and Continental to start implementing their domestic alliance. Northwest completed its acquisition of a controlling stake in Continental in November 1998, in defiance of a DoJ lawsuit seeking to block the transaction but after agreeing to various changes designed to prevent an actual transfer of control for a period of 10 years. This was quickly followed by FFP links and code–sharing on domestic and Asian routes, which now covers about 4,000 weekly flights between 261 cities and involves the exchange of about 2,000 passengers per day.

Since the other two domestic alliances have not implemented domestic code–sharing (nor are they likely to in the foreseeable future), Northwest and Continental gained a useful head start over their competitors. Northwest estimates that the Continental alliance added about $18m to its pre–tax earnings in the second quarter of the year, and is projected to generate about $80m in 1999. Expanded co–operation with longtime partners Alaska and Horizon has no doubt added to the revenue benefits.

There are obviously hopes that Continental, which already code–shares with Alitalia, will eventually formally join the transatlantic alliance, but that will have to be dealt with separately because of the DoJ lawsuit over the domestic alliance. The litigation, which is not active at present, has not in any way hindered the implementation of the domestic alliance, but it is a point of concern for the Alitalia antitrust application that the DoT has apparently requested extra information about Continental’s possible role in the Wings alliance.

Prospects

Northwest is expected to consolidate its financial recovery in the remainder of this year. The current First Call consensus estimate is a net profit of around $300m for 1999, rising to $400m in 2000 (see chart, page 12) — nowhere near the record $500m-$600m earnings posted in 1996 and 1997. However, there is considerable variation in individual analysts’ estimates, reflecting the many uncertainties that the carrier still faces.

If all goes well, the two contracts that remain open will be amicably settled by year–end. Labour costs will rise, but so will those of competitors — and Northwest has a distinct unit cost advantage to start with. But it still faces formidable challenges in Asia, where Northwest has the highest revenue exposure amongst the US carriers.

Since the first quarter of 1998 Northwest has reduced its Asian capacity by approximately 15% and restructured the network extensively in favour of more nonstop service in business–oriented markets. Although Asian countries such as Korea now appear to be on the road to recovery, Japan — where Northwest operates most of its flights — is still down in the dumps.

Nevertheless, the slump is believed to have bottomed out. Ticket sales from Japan have grown a little each month this year, so Northwest’s overall loss from Asian operations should be less in 1999 than last year.

But the carrier acknowledges that Asian financial recovery is still a long way off and that network adjustments will continue. Expanded co–operation with Asian carriers should also help. Over the past year Northwest has begun code–sharing with Air China (performing well) and its existing marketing partner Japan Air System and signed a Memorandum of Understanding on commercial co–operation with Malaysia Airlines.

Huge industry capacity additions have sharply reduced yields and profitability on the Atlantic routes this year. So, like some of its competitors, Northwest is now heavily dependent on the domestic market for profit generation.

The airline was previously lucky in that its route system had minimal exposure to low–cost operators. But that has now changed as carriers like Spirit, Sun Country and new–entrant AccessAir have discovered Minneapolis and Detroit in a big way and, by all accounts, are doing very nicely picking up traffic in some key business markets.

However, Northwest’s dominance of its hubs — which is now being even further strengthened by extensive utilisation of regional jets by its commuter partners — means that the carrier will not lose those battles.

| Current Fleet | Orders Options | Delivery/retirementschedule/notes | ||||||||

| 727 | ||||||||||

| 38 | 0 | |||||||||

| 747-100 | 2 | 0 | ||||||||

| 747-200 | 31 | 0 | ||||||||

| 747-400 | 12 | 2 | Delivery in 1999 | |||||||

| 757 | 48 | 25 | Delivery in 2000-2002 | |||||||

| DC-9 | 176 | 0 | ||||||||

| DC-10 | 41 | 0 | ||||||||

| MD-80 | 8 | 0 | ||||||||

| A319 | 48 (100) | Delivery in 1999-2003 | ||||||||

| A320 | 70 | 0 | Delivery in 2004-2005 | |||||||

| A330 | 0 | 16 | ||||||||

| CRJ-200LR | 0 | 12 (70) | Delivery in 2003-2004 | |||||||

| TOTAL | 103 (170) | Average fleet age = 20 years | ||||||||