How widespread is managerial incompetence?

August 1998

When airlines turn in poor results or go bankrupt, just how much is management to blame? In this article Aviation Strategy examines whether airlines should look a bit closer to home for the real reason for poor performance.

In general, the relationship between weak management and corporate performance is clear — poor management almost always results in weak company performance, but poor corporate performance does not necessarily mean the company has poor managers; there may be industry–specific or macro–economic reasons instead.

But although this relationship is obvious, few companies in any industry are willing to admit that current management is responsible for current woes. It usually takes a shareholder — often fund managers with large investments — to force managerial changes.

Aviation is no exception to this phenomena. In Europe and Asia in particular, management change usually occurs only after a sustained period of poor performance — and when chief executives go there is little (public) reflection on what effect their decisions have had.

The US experience

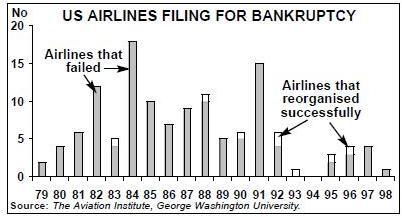

In North America, poor managerial performers last for less time than in other areas of the world, due to shareholder pressure, but even here the impact of poor management on airlines is rarely discussed. However, the issue may now be getting some attention following the release of a study by the Aviation Institute at George Washington University* into why new entrant airlines fail.

The study almost entirely dismisses predation as a factor in start–up failure. Instead the report’s author, Darryl Jenkins, Director of the Aviation Institute, cites poor management as the main cause of corporate failure.

According to the report, its survey of Chapter 11 and Chapter 7 filings since 1979 found that the following reasons are most regularly given by airlines for their failure:

1) Operational plans

2) Excessive debt

3) Escalating costs

4) Inadequate traffic

5) Economic downturns

6) Inability to obtain adequate financing

7) Lack of management expertise

The report claims that the common link between most of these is management. It appears that airlines that fail seem to have an amazing ability to hire poor management. The report found that of all the airlines that failed in the 1990s, 97% employed senior executives who had been involved in a previous Chapter 11; 75% had executives who were involved in two previous Chapter 11s; more than 50% had executives with experience of three filings; and 15% had executives who were involved in four or more previous filings. In Aviation Strategy’s opinion these facts are somewhat misleading because what the report does not do is give comparable figures for managements at airlines that do not fail — but nonetheless the figures do raise the question of just what calibre of executives do failed airlines actually employ?

The bad management effect

And what are the precise characteristics of poor management? According to the report, the most telling contribution of weak management is a “basic inability to plan a route network”. Evidence for this comes from a tendency at airlines that fail for them to enter and exit markets with enormous frequency. Over the last five years, the average length of time a start–up remains on a city pair before it retreats from the market is six months. And predatory pricing is not to blame for market exit, the report claims. If routes where predatory pricing has been alleged are taken out of the survey, the average time spent by start–ups in routes before they retreat is the same. With or without predatory pricing, there is no statistical difference in how long start–ups stay in markets.

The report also states that very few airlines that file for bankruptcy cite predatory pricing as a cause of their failure (although surely that in itself does not mean that predation does not exist?).

The study also looks at the most successful new entrant — Southwest — and compares it with the failures (although, again, this can be criticised since Southwest existed long before US deregulation and, critically, enjoyed regulatory protection during its early growth at Dallas Love Field).

In particular, the report highlights Southwest’s tendency to offer high frequency in the markets it enters. This contrasts with most start–ups, which usually offer low frequency, resulting — it is claimed — in low average aircraft utilisation rates, high unit costs, low marginal revenue and high marketing and station costs. It seems it is much better to offer high frequency service in a relatively small number of new markets each year (as Southwest does) than offer low frequency and rapid market growth.

However, what the report doesn’t go on to do is examine just why managements adopt a low frequency/high growth strategy? Is it by choice or do start–ups have no other option? Often start–ups have no choice but to aim for rapid growth — if you are tiny to begin with, any growth is rapid. And other airlines do try their best to make it impossible for start–ups to launch with higher frequencies.

Nevertheless, Jenkins says: “The problem with growth is managing it. It takes up every available cent, causes costs to go up rapidly and results in confusion for management, who often get reports back too late to really know what is going on.”

As growth gets unmanageable, a chain of events is set in motion — break–even load factors rise (to the high 60s to high 70s), leading to poor revenue management and pricing. But it would be wrong to condemn growth as a strategy for start–ups — surely it is more accurate to say that it is the execution of growth is the real problem.

Lessons of a flawed study

Although Jenkins’ study consists more of assertions than detailed analysis, it does serve to bring the issue of poor management to the fore, and it has brought forward a barrage of counter–arguments by critics. Most loud are those observers who have traditionally blamed predatory behaviour by established competitors for the demise of start–ups, and not poor management. They emphasise the concerns about the study that Aviation Strategy has pointed out, but disingenuously ignore the point that poor management is a key factor in start–up failure.

The reality lies between the two extremes. Yes, predation is a major cause of start–up failure (although this depends on how you define predation), but poor managerial decisions do have a greater impact on success or failure than many realise. Often the two factors overlap — start–up managements often choose markets where predation by an established competitor is inevitable, even if it is illegal.

Poor management and the reasons behind it are certainly something that the industry needs to consider further. Perhaps there is one factor that many observers overlook. Unlike other industries, aviation is regarded as sexy, and that often attracts not just pure entrepreneurs but also former industry employees (from pilots to financiers) who want to stay in the industry and believe that they can do better than others. Perhaps that is the real cause of poor airline management.