Alaska Airlines comes in from the cold

August 1998

Alaska Airlines, the smallest of the US major carriers, has returned to good profitability thanks to its ability to reduce drastically unit costs while maintaining excellent service quality. Its sister company Horizon, the nation’s sixth largest regional carrier, is now, in turn, staging a turnaround. Record profits, a vastly improved balance sheet, a $425m new aircraft order and good expansion opportunities in a stabilised West coast competitive environment make the prospects for Alaska Air Group (AAG) look particularly promising.

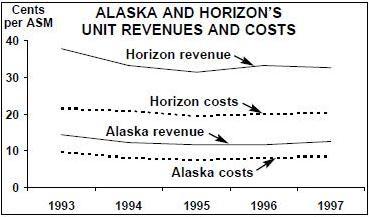

This is in total contrast to the situation three or four years ago, when Alaska Airlines looked very much like a loser when it was suddenly caught in the fierce market share battles between Southwest and United’s Shuttle. Alaska’s unit costs, at almost 10 cents per ASM in 1993, were among the highest in the industry. It was a full–service carrier, charging high fares and focusing on business traffic. Apart from some limited damage inflicted by low–cost carriers like MarkAir (now defunct) in the early 1990s, Alaska had hitherto faced only gentle competition from the other majors.

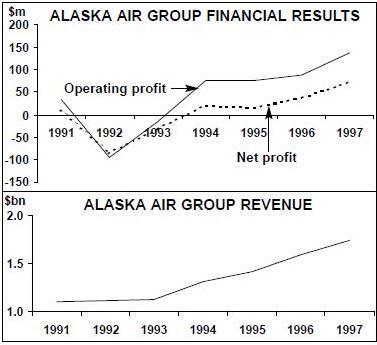

The carrier seemed largely unprepared when Southwest and United’s Shuttle saturated the bulk of its markets with extremely low fares. The impact was to slash Alaska’s yield by 14.2% in 1994 and by another 5% in 1995, which the company called one of the roughest years in its 64- year history. Although AAG had managed to return to profitability in 1994 (after two years of net losses totalling $116m), its net profit fell in 1995 and remained at a very marginal 1–2% of revenues up to and including 1996.

However, the latest financial results indicate that Alaska managed to turn the potentially disastrous developments to its advantage. This was largely accomplished through a rapid and extremely successful cost–cutting programme, which appears to have had minimal negative impact on service quality, though lower fuel prices and a stabilised competitive environment have also helped.

AAG posted a $15.1m net profit for the fourth quarter of 1997 — usually a loss–making period — and a record $72.4m profit for 1997, which was nearly double the previous year’s $38m. In the first quarter of 1998, traditionally Alaska’s toughest, the company earned a $13.1m net profit, compared with a $5.7m loss a year earlier. In mid–July, analysts were expecting a net profit of around $30m- $35m for the quarter ended June 30.

Impressive turnaround

Alaska’s cost–cutting programme, which was instigated in 1993, included extensive fleet rationalisation and restructuring. The carrier cancelled some aircraft orders and began to reduce its fleet to just two types, which included the disposal of its 727s. It also renegotiated aircraft leases and refinanced debt.

Some marginal one–stop routes were terminated, often in favour of operating those sectors nonstop. Alaska also laid off around 600 mostly white–collar workers and cut the number of flight attendants manning aircraft. When threatened by fleet cuts and furloughs, its pilots agreed to a 5% pay cut and reduced pay rates for additional flying.

The combined effect of the cost cuts, which amounted to about 10% or $110m per year, and continued capacity growth was to slash Alaska’s unit costs by 22% in just two years, to 7.71 cents per ASM in 1995. This was probably the closest that it could get to Southwest’s levels, given the higher costs involved in having significant operations in the state of Alaska.

Since then the airline’s unit costs have risen (8.51 cents in 1997), in large part due to growth but also because of inevitable wage increases. Flight attendants (AFA) secured higher pay in 1994, dispatchers (TWU) in 1996 and pilots (ALPA) late last year. However, the long–term deals offered increased productivity, as well as staffing and scheduling flexibility. While talks continue with the mechanics (IAM) and the AFA contract becomes amendable next March, Alaska is in the enviable position of not having to start negotiating with pilots until the beginning of 2003.

The earlier cost cuts were painful enough to lead to the departure of Alaska’s former CEO Raymond Vecci. The board fired him, citing differences in management style, in early 1995, even though by then recovery was underway. With hindsight, Vecci has been given the bulk of the credit for the turnaround.

Even when the main emphasis was on cost–cutting, Alaska had the foresight to invest extensively in labour–saving technology. It was early to provide electronic ticketing, which offers major savings in distribution costs, and claims to have been the first US carrier to sell tickets on the Internet.

But the most impressive aspect of Alaska’s deep cost–cutting was that it appears to have had little adverse impact on its traditionally excellent service quality. The airline has continued to receive prestigious awards from travel organisations and perform well in the DoT’s service quality rankings.

By continuing to pay exceptional attention to detail, both in the air and on the ground, Alaska has retained much of the high–yield business travel segment. Although some of the extra luxuries that it was previously famous for have had to go, product differentiation appears greater now that the main competitors are Southwest and the Shuttle rather than the large majors. But by lowering its fares to match those of the low–cost competitors, Alaska is obviously now also carrying more leisure traffic.

The stabilisation of the West coast competitive situation over the past 18 months has provided much relief. This began when the Shuttle conceded defeat to Southwest, pulled out of many competitive markets and focused on feeding United at its San Francisco and Los Angeles hubs. The two carriers now co–exist relatively peacefully, while Southwest itself is focusing its main efforts on the East coast.

Alaska attributed much of the 1997 financial improvement to the “absence of silly fares” that it had in 1996. Its unit revenues rose by 7.8% and yield by 7.1% last year, and the positive trends have continued. Over the past 18 months, Alaska’s revenue growth (over 9% annually) has been the highest among the majors, even exceeding Continental’s (which is in the middle of a major growth phase).

While the policies initiated by Vecci were continued by his successor, John F. Kelly, there has also been a new emphasis on growth in existing markets. Alaska’s capacity rose by 7.3% in 1996, 3.6% in 1997 and 7.4% in the first six months of this year. Much of this has been achieved with the same fleet, as the more flexible union contracts have made it possible to improve aircraft utilisation (from just over eight hours per day in 1993 to 11.4 last year).

Since traffic growth has exceeded capacity addition, Alaska’s load factors have also improved. The average passenger load factor rose from the low–60s typical up to and including 1995 to 66% in 1996 and 67.3% last year.

The efforts of Horizon, Alaska’s regional subsidiary, to adjust to increased competition in its markets are also finally beginning to pay dividends. After merely breaking even in 1996, the regional carrier reported a $6.3m pre–tax profit on $303.6m revenues for 1997, and also a small profit for the March quarter.

The turnaround was attributed to lower fuel prices, reduced costs associated with a simplified fleet and a longer average stage length. The fleet simplification has meant the retirement of the Dornier 328s, Metros and F28–1000s, and eventually also the Dash 8–100s, to narrow the fleet down to just two types. After operating a complicated route network from four different hubs, the carrier is now focusing on more long–haul flying out of a single Seattle hub.

As a result, after years of unit costs persistently exceeding 20 cents per ASM (the highest among the US regional carriers), Horizon’s unit costs fell by a substantial 12.5% in the first quarter. Further cost reductions are anticipated as the streamlining of the fleet takes full effect.

The bottom line improvements at AAG have been accompanied by a substantial strengthening of the balance sheet. Long–term debt and capital lease obligations have fallen from $590m at the end of 1994 to $335m at the end of March 1998, while in the same period shareholders’ equity rose from $191m to $553m. The balance sheet and leverage ratios improved further in the June quarter as the company completed the redemption of $126m of debentures due in 2005. The Group had $251m in cash on March 31, up from $102m at the end of 1996.

In recent months Alaska has been one of only two US major carriers to see their corporate ratings upgraded by credit rating companies (the other one was US Airways). S&P recently revised AAG’s rating from BB- to BB+, citing “improved financial profile due to higher earnings as well as a reduction in balance sheet debt”.

The improvements have also meant a steady rise in AAG’s share price, from $20-$25 in the second half of 1996 to about $40 at the beginning of 1998, and a further rally to almost $60 by mid–July.

Fleet plans

Alaska currently operates a fleet of 80 aircraft: 42 MD–80s, 30 737–400s and eight 737–200s (Feb 26). It is in the process of eliminating the MD–80 fleet, in order to achieve the substantial commonality benefits offered by an all–737 fleet. The carrier’s improved cost structure and the more stable West coast competitive environment have positioned it well for growth, while the reduction of debt has eased the financing of major new aircraft acquisitions. The past two years have seen several new Boeing aircraft orders, for a flexible mix of 737 variants to fit short, intermediate and long–haul markets.

The process began in September 1996 when Alaska ordered 12 140–seat 737–400s and took 12 options, valued at about $540m. The deliveries of that batch began about a year ago, replacing the older MD–80s on a one–for–one basis.

In November 1997 Alaska became the launch customer for the 737–900 when it announced a firm order for 15 aircraft (two -400s delivered this year, three 122–seat -700s due in 1999 and 10 — 900s due in 2001–2002) plus 10 options, valued at over $1bn. The carrier said that the 174–seat 737–900 was a perfect fit for its high–volume, long–haul markets.

In May the carrier placed a $425m order for six 737s, including five 700–series and one 400- series, plus options for four “next generation” 737s, for delivery in 1999–2001.

This latest order brought to 50 the number of 737s currently on order and option. Five more -400s are due for delivery this year, followed by eight -400/700s in 1999 and up to eight -700s in 2000. If all the options are taken, Alaska’s fleet will expand from the present 80 to 130 in six years’ time.

For some years already, Alaska’s fleet has been the youngest among the majors, currently averaging 7.6 years of age. The fleet also became the quietest in December, when Alaska completed the hush–kitting of its remaining 737–200s — the first US major to achieve an all–Stage 3 fleet.

The aim at Horizon is to eliminate the currently 21–strong Dash 8–100 fleet in favour of the Dash 8–200s. There are now 17 of the 200–series in the fleet, with further deliveries due in a steady stream through 2004. The F28–4000s (17) have already replaced the earlier F28–1000 fleet.

Route expansion strategy

Alaska operates a north–south network along the West coast, stretching from the Russian Far East to Mexico. Together with Horizon, it currently serves 76 cities in Alaska, Mexico, Canada,Russia and seven Western states.

Over the past few years, much effort has gone to strengthening the key strategic routes, namely those that link Seattle with the Bay area and Los Angeles, with substantial frequency additions. As a result, Alaska has not only retained but improved its number one position in most of those markets. Its share of Alaska–West coast passengers has risen from 56% in 1994 to 75% at present, while the Pacific Northwest to Northern California market recorded a similar increase.

The airline appears to have lost only a couple of percentage points in market share on Pacific Northwest to Southern California routes (about 40% at present), where competition has been the fiercest.

In 1996 Alaska began serving Vancouver in Canada from San Diego, and last year, thanks to the full implementation of the open skies agreement, expanded service there from several West coast cities. The idea is to tap the Canadian leisure market destined to winter sun. At the same time, the carrier has boosted winter services to Mexico. A fifth Mexican destination, La Paz, will be added in October with flights from Seattle via Los Angeles.

Alaska has also continued to boost its services to the Russian Far East, which began in 1991 and now cover five destinations. While otherwise much of the recent focus for new expansion has been in the south, the state of Alaska remains an important market, accounting for about a quarter of the carrier’s total traffic.

Having found a good niche, Alaska has no plans to divert away from the north–south flying pattern and venture further east to more competitive pastures. The new aircraft will be used to boost service in existing markets and introduce more non–stops between cities already served.

Position vis-à-vis alliances

Alaska’s long term strategic position in a future domestic marketplace possibly dominated by a few mega–alliances appears reasonably secure because of its longstanding co–operation with Northwest. The association dates back to 1989, when Horizon began code–sharing with Northwest, and Alaska followed in the early 1990s.

The link–up is a natural one because of Northwest’s extensive Asian operations. After code–sharing on numerous domestic and Mexico routes, about a year ago Alaska and Northwest expanded their co–operation to Alaska’s flights in the Russian Far East. The carriers offer convenient connecting flights, through fares and check–in processes and reciprocal FFPs.

As an indication of things to come, in early June Alaska and Northwest’s longstanding partner KLM signed a marketing alliance, which also includes Horizon, to offer reciprocal FFPs and to code–share on selected flights. Alaska will carry KLM’s code on certain flights connecting with Northwest–operated KLM flights at Seattle and with KLM–operated service at Los Angeles, San Francisco and Vancouver (the latter subject to government approval). The deal also envisages co–ordination of schedules and connections, as well as linked computer check–in and reservations systems.

Alaska was also one of the four US airline signatories in the recently–forged marketing and code–share agreement with Air China. Deals like that may pave the way for code–share opportunities with Continental and America West.

Prospects

Alaska Air Group’s 1997 net profit margin of 4.2%, though similar to America West’s, still lagged behind those of the large majors by a few percentage points. Consequently, its main challenge now is to improve profit margins, while coping with the additional demands posed by growth.

The further improvements could come from higher load factors, yields and aircraft utilisation, as well as the commonality benefits and scale economies offered by the eventual all–737 fleet. However, keeping unit costs under control poses a major challenge after years of heavy cost–cutting.

The traffic and load factor statistics for the second quarter indicate a continuation of positive trends. Most analysts view the company’s earnings prospects as excellent and still rate its shares as a buy, though some now feel that the stock is becoming overvalued. The current First Call consensus forecast is a net profit of $4.63 per share for 1998 (up from $3.53 last year) and $4.74 for 1999.