Europe's charter airlines await fall-out of industry consolidation

August 1998

Europe’s charter airlines have long been misunderstood (and unappreciated) by many observers. US–based analysts predicted their demise with the advent of European deregulation because they drew false analogies with their supplemental carriers. Others forecast that charters would switch to scheduled mode, bringing no frills/low fares into the European market. Neither development has happened. In this briefing Aviation Strategy takes a close look at European charter airlines and an industry that, nonetheless, has undergone fundamental change over the last few years.

Although deregulation has broken down artificial barriers (such as regulations preventing charters from selling direct to the public, or stopping scheduled airlines gaining access to charter markets), the distinction between charter and scheduled operations remains. The evidence is clear — there have been relatively few examples of charter airlines becoming successful scheduled players, or of scheduled airlines entering charter markets.

The main movers from charter to scheduled are shown in the table below. A distinction should be made between charter airlines that operate scheduled flights on traditional charter routes — such as many German carriers — and those charter airlines that have entered truly scheduled markets. That latter category — the true cross–marketers — consists mainly of Lauda–air, Virgin Express (ex- EuroBelgian), Spanair and Air Europa.

This indicates that charter airlines have — by and large — remained specialists in serving the markets and routes they know best. Many charters that have tried to enter the scheduled business in a big way — such as Britannia Airways in the 1980s — decided sooner or later that their long–term future lay in charter operations only.

And in the opposite direction — from scheduled to charter — there has been even less movement. Indeed many national airlines have sold their charter subsidiary — SAS and Scanair, Air France and Air Charter, and British Airways and Caledonian, to name but a few.

But why is this? Essentially, there are four reasons for why the charter and scheduled sectors remain distinct despite European deregulation:

- Differences between the charter and scheduled product;

- European tourism flows;

- Differences in charter and scheduled fleets; and

- The importance of vertical integration in the tourism industry.

Product differences and tourism flows

Charter and scheduled products do not seem to be converging at all — or at least so far no supplier has been willing to bring them closer together. Despite some investment in new equipment, by and large the charter product consists of good soft spec (cabin crew service etc) disguising poor hard spec (seat pitch, food quality etc). Apart from seat–only sales, holidaymakers do not know how much their flights cost — all they want is the lowest holiday price possible. And there is even some indication that in the German market — where traditionally the charter product has been more upmarket and pricier than the rock–bottom UK market — there is now a tendency towards the traditional cheap and cheerful UK–style charter.

Given this, and other factors such as fixed stays, round–trips and single sectors, the charter airline has to operate within a very different set of parameters than that of a scheduled carrier. And this makes it very difficult for one airline to change from one type of product to another with ease.

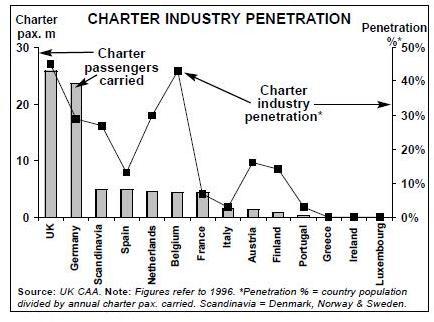

Similarly, the north–south Europe summer holiday flow remains the bedrock of the charter industry. The chart below shows how the charter industry has penetrated the deepest (in terms of what percentage of the population takes a charter flight) in countries in the north of Europe — UK, Germany, Scandinavia, the Netherlands and Belgium. Elsewhere — with the exception of Spain — charter penetration is almost negligible. Simple geography, therefore, and the desire of north Europeans to spend summer holidays by the Mediterranean still remains a strong barrier to charter operations being successful anywhere other than from northern Europe.

Heterogenous fleets

Given the differences in product compared with the scheduled market, an airline serving the charter market generally needs a different type of aircraft to a scheduled carrier. The combined fleet of Europe’s main specialist charter airlines (see table, right) has an average size of more than 200 seats, and many aircraft are larger than those used traditionally on scheduled routes. And in airports such as London Gatwick, even bigger aircraft may be the the only answer to slot constraints.

Where the charter market is smaller — intra- Spain for example — smaller charter aircraft can be used more easily for scheduled services. But in the two largest markets, outbound from Germany and the UK (which together account for almost two–thirds of all charter passengers in Europe), economies of scale are best exploited by using relatively large aircraft.

Integration and consolidation

The main barrier to charter and scheduled airlines moving seamlessly between the two markets is the trend to vertical integration and consolidation within the European travel industry.

Vertical integration is now an accepted practice in the UK travel industry, following a 1997 investigation by the Monopolies and Mergers Commission (MMC) into complaints by smaller operators and agents that the large groups were squeezing them out. In a landmark decision the MMC ruled that the large integrated travel groups in the UK were “broadly competitive”.

This led to a further round of consolidation in 1998, which has led to the emergence of four main travel groups — the so–called “Big Four”. In June First Choice bought Unijet — the UK’s fifth–largest operator, with 10% of the UK market — for $180m. Unijet’s charter airline, Leisure International, will be merged into First Choice’s Air 2000 to form the UK’s second largest charter carrier behind Britannia. (Unijet was 34% owned by KLM.) At the same time First Choice also bought Hayes & Jarvis, a specialist long–haul operator, for $39m — long–haul is the fastest–growing segment of the UK package holiday market. Also in June 1998, Thomas Cook — owned by Westdeutsche Landesbank (WestLB) — bought Flying Colours for an estimated $106m. Flying Colours has 4% of the UK package holiday market (through products such as Club 18–30) and in this case Thomas Cook’s charter subsidiary, Airworld, will merge into Flying Colours’ fleet.

The UK’s Big Four — Thomson (which was floated in London in May at $3.1bn), First Choice, Airtours (which failed in its bid to buy Unijet) and Thomas Cook — now control 80% of the UK’s $62bn a year package holiday market. And that market is growing at an estimated 8% per year.

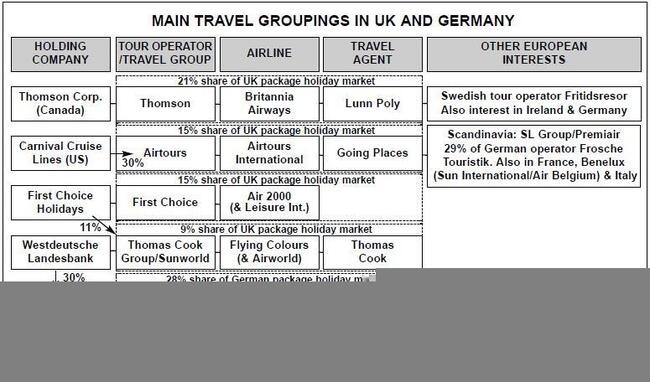

The major travel groupings in the UK (and Germany) are shown on page 12. Only First Choice/Air 2000 does not have a travel agency chain, although some analysts predict a link–up with the AT Mays chain, owned by Carlson.

The same vertical integration and consolidation process is also occurring in the other major European charter market — Germany. Its travel industry has traditionally been comprised of an almost impenetrable maze of cross–shareholdings, but over the last 12 months two major and distinct travel groupings have emerged — dubbed the Yellow and Red alliances after their respective logos.

The Yellow alliance is based around C&N Touristic, a 50:50 joint venture formed by the 1997 merger of Condor — Lufthansa’s charter subsidiary — and NUR Touristic, the tour operator owned by German retailer Karstadt. C&N has sold travel agency Euro Lloyd (owned 49% by Lufthansa and 51% by Karstadt) to Kuoni, but still has substantial travel agency presence via NUR. The full structure of the Yellow alliance is set to be unveiled in October.

The Red alliance is centred around German conglomerate Preussag, which in 1997 bought the travel group Hapag–Lloyd for $1.5bn in order to link it to TUI (Germany’s largest tour operator). However, the German Cartel Office insisted that it would only give its approval for this deal if WestLB — which owns 30% of Preussag — sold its 34% stake in airline/tour operator LTU (see page 13).

The charter mantra

For charter airlines, the implication of this vertical integration and consolidation in national markets is clear — they need to be part of a major travel grouping in order to guarantee access to the tour operator contracts they rely on. The future for the remaining independent charters looks increasingly difficult, because relying on supplying marginal capacity to the large travel groups in the UK and Germany is fraught with danger. For example, Wolfgang Beeser — the chairman of NUR Touristic — says that the proportion of seat capacity it buys from Condor will rise from the current 40% to around 60% through the dropping of non–Yellow alliance charter airlines.

Elsewhere, UK tour operator Inspirations — which owns Caledonian and accounts for 4% of the package holiday market — may be too small to survive long–term against its bigger rivals. Last year Inspirations was bought by the US–based Carlson Group, although in June Carlson served a writ against former Inspirations directors, accusing them of misrepresentation relating to the sale.

The necessity for a link–up with a large travel group is a point that European scheduled airlines with charter subsidiaries have realised only comparatively recently. Unless they can ally the charter offshoot with a major tour operator — as Lufthansa has done with Condor — for the reasons already explained they face no alternative but to sell the charter subsidiary.

When British Airways sold Caledonian in 1995 it stated that it made the move because successful charter operations needed to be vertically integrated with a successful tour operator. KLM too is selling its 34% stake in Unijet/Leisure International (although it still owns Dutch charter airline Martinair), Air France and SAS have offloaded their charter subsidiaries, while Iberia is deciding whether to turn its loss–making charter airline, Viva Air, into a low–cost scheduled carrier.

Pan-European consolidation

But over and above vertical integration and consolidation within countries, charter airlines also face the consequences of increasing consolidation across countries. The German Cartel Office’s ruling on WestLB and LTU marks the limit of domestic consolidation, and with most of the small players now snapped up in the UK, any consolidation between the Big Four would tip a merged group past the crucial 25% market share mark, which is the key determinant of whether the MMC would intervene. And that is why the Big Four, as well as the two German groups, are now looking to expand overseas.

Although the German groups have a head start in foreign expansion, the UK companies are catching up fast — and their prime target is Germany itself, particularly now that the complex cross–shareholdings are being broken down. The German charter market differs slightly from the UK in that German package holidaymakers have traditionally preferred a higher quality, higher priced product. There are also regulations that forbid fare discounting outside a specified period.

But these norms were challenged in 1997 by Thomson, which set up a charter airline subsidiary — Britannia Airways Germany — in partnership with local tour operator FTi Touristic. According to some estimates, Britannia’s German operation offers tour operators fares that are up to 30% lower than German charter airlines’ prices. Thomson is also looking for opportunities in the Benelux markets, and in 1997 bought Scandinavian tour operator Fritidsresor and its charter airline Blue Scandinavia (renamed Britannia AB) for $425m.

Airtours was not far behind Thomson. In May 1998 Airtours bought 29% of German tour operator Frosche Touristik for $28m (and has an option to acquire the rest of the privately–owned company in 2002). Frosche has 5% of the German package holiday market, and also has more than 100 franchised travel agents.

However, Thomson and Airtours’ forays into Germany so far are small beer compared with the main prize on offer — LTU. As both a tour operator and an airline LTU is a key player in the German travel industry, and beyond. For example LTU has won a major contract to fly for Swiss operator ITV (itself a 1997 merger of three Swiss companies), after ITV was gazumped by Swiss rivals Kuoni and Hotelplan, which chartered the entire summer 1998 capacity of Balair/CTA and TEA Switzerland.

Yet the German Cartel Office’s ruling means that a German buyer with large existing travel interests is out of the question for LTU, so this theoretically provides an ideal opportunity for Airtours or Thomson to grab a major share of the German market in one go.

WestLB, though, has other ideas. It may have ruled out any acquisition by UK buyers by transferring its LTU stake to an insurance company and setting it a three year deadline to find a suitable permanent buyer. This delay is likely to encourage German buyers with few existing travel interests to come forward and put together a high enough price to outbid any UK competition. A so–called “Third Force” in Germany’s travel industry would be the result — but WestLB would far prefer that to Airtours or Thomson acquiring LTU.

The main competitor to Airtours and Thomson in German may come from the Swiss. Kuoni has bought the travel agency Euro Lloyd from C&N and is believed to be looking for further German acquisitions, while the SAirGroup is reported to be interested in LTU.

Outside Germany, Airtours and Thomson have pretty well sewn up Europe’s third–largest charter market — Scandinavia. Although Airtours’ SLG has recently faced difficulties due to overcapacity in the local market, together Airtours and Thomson account for two–thirds of package tour sales in Scandinavia.

Two options for charters

The chief determinant of the charter industry into the next decade will be pan–European tour operator and travel group consolidation — not charter airline consolidation. But as tour operators consolidate across Europe, their respective charter airlines will consolidate too.

It will be interesting to see just how far UK travel companies penetrate the German market, and whether their associated lower–cost charter airlines can win large chunks of the outbound market. Whichever company — British or otherwise — acquires LTU will have a real opportunity to challenge the Red and Yellow alliances.

For independent charter airlines though, the future holds one of two options — to give up independence and merge/align with one of the major travel groups/tour operators; or to battle it out with the remaining independents for the marginal charter capacity needed by the big group.

On the first option, time may be running out to find suitable benevolent parents. The large groups have charter subsidiaries of their own and are mostly interested in acquiring tour operators first and charter capacity second. Guaranteed demand for the holiday product is the scarce resource that travel groups most urgently seek — not charter capacity.

The second option — remaining independent — is fraught with danger. If a charter airline is too reliant on contracts with independent tour operators, there is always the possibility that the operator may get taken over by one of the large groups, which will then install its own in–house charter carrier.

This happens to even the larger charter airlines. For example Thomson won a three year contract to supply charter capacity via Britannia to the German tour operator Frosche. But since that deal Airtours has taken a stake in Frosche, and so when the contract ends Airtours International is likely to step in and replace Britannia. At least in this case Britannia is linked to a travel giant of its own, and the Frosche contract is only a small proportion of its overall business.

The remaining independent tour operators may just decide to set up their own charter airlines anyway. Spanish group Viajes Iberia, for example, replaced Airworld (which it sold along with operator Sunworld to Thomas Cook in 1996) with a new charter airline of its own — Iberworld.

The independent charter airlines, therefore, may prefer to supply the marginal capacity needed by the large travel groups (on extended contracts, if possible), rather than the bulk of the capacity needed by a small, independent (and vulnerable) tour operator. But competition will be tough, and only the non–aligned charter airlines with rock–bottom costs (and perhaps smaller capacity aircraft) will survive. And in times of recession it is the independents that face the most danger — Dan–Air is the perfect example of this.

However, large travel groups will always need marginal capacity at peak periods, so there will always be a niche for small, independent charter airlines. But the days of the medium–to–large sized independent charter airline are firmly over.

| December 1992 | December 1997 | |||

| Routes | Flights | Routes | Flights | |

| Domestic | ||||

| Air Europa | 0 | 0 | 57 | 1,663 |

| Spanair | 0 | 0 | 22 | 1,129 |

| Lauda-air | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| International | ||||

| Air Europa | 0 | 0 | 5 | 86 |

| Spanair | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| Monarch | 4 | 30 | 6 | 69 |

| Virgin Express | 0 | 0 | 7 | 797 |

| LTU | 0 | 0 | 64 | 479 |

| Aero Lloyd | 0 | 0 | 32 | 157 |

| Hapag-Lloyd | 0 | 0 | 70 | 661 |

| Condor | 2 | 8 | 65 | 458 |

| Transavia | 7 | 160 | 13 | 246 |

| Lauda-air | 2 | 39 | 14 | 517 |

| Condor Britannia | Hapag- | LTU | Aero | Airtours Monarch Germania | Air | TOTAL | |||||

| Airways | Lloyd | Lloyd | Int. | Airlines | 2000 | ||||||

| 737-300 | 9 | 9 | |||||||||

| 737-400 | 11 | 11 | |||||||||

| 737-500 | 5 | 5 | |||||||||

| 737-700 | 6(6) | 6(6) | |||||||||

| 737-800 | 3(13) | 3(13) | |||||||||

| 757-200 | 18 | 19(2) | 10 | 4 | 6 | 9(1) | 66(3) | ||||

| 757-300 | (12) | (12) | |||||||||

| 767-200 | 6 | 6 | |||||||||

| 767-300 | 9 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 22 | ||||||

| DC-10-30 | 3 | 1 | 4 | ||||||||

| MD-11 | 4 | 4 | |||||||||

| MD-80 | 10 | 10 | |||||||||

| A300-600 | 4 | 4 | |||||||||

| A310-200 | 4 | 4 | |||||||||

| A310-300 | 4 | 4 | |||||||||

| A320-200 | 3(3) | 6(2) | 10 | 5 | 4 | 28(5) | |||||

| A321-200 | 2(1) | 1 | 1(2) | 4(3) | |||||||

| A330-200 | (2) | (2) | (4) | ||||||||

| A330-300 | 6 | 6 | |||||||||

| TOTAL | 33(15) | 30(2) | 27(13) | 25 | 18(3) | 18(2) | 17(4) | 15(6) | 13(1) | 196(46) | |