Aegean: Conservative success amid Greece’s financial crisis

April 2018

Athens-based Aegean Airlines continues to prove that success is possible for an airline defined neither as an LCC nor a FSC.

At the end of March Aegean announced an order, cautiously described as a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU), for up to 42 units of the A320neo family, after a close-run competition against the 737MAX. The firm element of the order is for 30 units, of which at least 10 will be A321neos, the rest A320neos unless Aegean chooses to convert them to A321s.

The order of valued at $5bn at list prices (so maybe around $3bn after discounts). The engine selection — either P&W’s 1100G or CFM’s LEAP — will be made in June, but either is expected to deliver 15% fuel saving compared to the standard A320 plus increased range of 600-1500km. There should also be major MRO saving on maintenance costs which have been escalating alarmingly — by 30% in 2017 — for its relatively elderly fleet (a quarter of its A320s are over 10 years old).

Aegean’s previous order for new equipment was back in 2005 when it committed to the A320. Since then it has IPOed on the Athens stock exchange, acquired the former flag-carrier Olympic Air and managed to prosper through the worst financial and economic crisis to hit a European country in the post-WW2 era.

Greek GDP in 2017 was still 28% below pre-crisis levels but there have been signs of recovery in economic activity, government finances have improved enough to allow the end of EU-imposed austerity controls by this summer, and tourism is buoyant (arrivals up from 18m in 2013 to 27m last year).

Moreover, Greek official statistics rarely reflect a completely accurate picture — they grossly overestimated the strength of the economy when Greece joined the eurozone and now underestimate the scale of new investment in the Athens area.

Aegean itself lists some of the key projects: the Chinese company Cosco’s plans for a transshipment hub; the luxury developments along the Athens Riviera, Niarchos Foundation’s various civic building projects; new five-star hotels; and the €7-10bn regeneration of the prime real estate formerly occupied by the old airport, Hellinikon; Fraport’s investment in the regional airports.

2017 results

In 2017 Aegean’s revenues increased by 11% over 2016 to €1.13bn, while EBIT improved from €58.8m to €100.4m, and at the net level profits nearly doubled to €60.4m from €32.2m. The EBIT margin was therefore 8.9%, not quite in the Ryanair class but comparable to easyJet.

The balance sheet is strong with long term liabilities at €87.1m being just 13% of total assets, partly reflecting Aegean’s fleet policy of concentrating on operating leases. Liquidity is also strong with unrestricted cash and equivalents standing at €286m at the end of last year.

Passenger volume was up 6% in 2017 to 13.2m, mostly due to growth in international routes, which, combined with modest capacity growth of just 2%, pushed up average load factor to 83.2% from 77.4%. As a result, Aegean was able to reverse a five-year decline in unit revenue — in 2017, with yields more or less constant, RASK increased 9% to €¢6.9.

Its average fare — around €85 — is well above that of its LCC rivals, but generally below Legacy carrier pricing. Aegean makes a genuine effort with service quality. Its A320s are operated internationally with a business class section, and onboard service, with free food and drink in both cabins, is now clearly superior to that offered by BA on intra-European flights.

CEO Dimitrios Gerogiannis, in a recent presentation in London emphasised how, for instance, cabin staff record any complaint or issue from a passenger on their iPads, and that passenger is then automatically contacted by a customer-relations person as soon as is possible. It sounds impressive, in sharp contrast to the LCC or Legacy experience.

Aegean manages to control unit costs at easyJet-type levels but 30-40% above ULCC levels— in 2017 it reported CASK of 4.1€¢ ex-fuel, 6.3€¢ total, with a 905km average stage length. Labour and overhead costs are competitive, largely as a result of Greece’s financial and economic crisis, but Athens International Airport (AIA) levies some of the highest airport charges in Europe, comparable to Heathrow’s.

Aegean’s position between the LCCs and the FSCs illustrated by the graph which summarises capacity shares on its main routes. Aegean competes head to head with Ryanair on the dense domestic routes, where Ryanair should have a cost advantage, and is more flexible in adjusting capacity to match widely fluctuating seasonal demand. On most of the other, longer European routes, Aegean competes mostly against flag-carriers where it has a distinct advantage in terms of both unit costs and service quality.

The main non-flag-carrier competition has come from Air Berlin, which has now mostly been taken over by Lufthansa. As Aegean is a Star Alliance member and provides intercontinental feed at Frankfurt, this development is probably advantageous for Aegean.

Ryanair is the second largest competitor by seats offered in the Greek market but it has not expanded as rapidly as expected (or feared). As the chart illustrates, Aegean had grown steadily, by about 7% pa in ASK terms, since the 2013 retrenchment, following its absorption of Olympic Air. Ryanair entered the market in 2013, surged ahead then levelled off — interestingly, the same pattern as in many of the CEE markets it entered in competition with Wizz (see Aviation Strategy, March 2018). easyJet, long established at Athens, has stagnated over the past four years.

Ryanair has been unable to persuade Greek airports to comply with its operating strategy. AIA, jointly owned by a Canadian pension fund and the Greek state, rejected Ryanair’s offer of delivering 10m passengers and/or providing zero cost seats on some island routes if fees were to be drastically cut. In April this year, Fraport which owns a 40-year concession to operate 14 regional airports and is committed to investing €230m by 2020, increased it landing charges by about 30%. This was from a very low base and resulted in a new landing fee equivalent to just over €1 per passenger, but other charges and taxes bring the total up to €14 per departing passenger. Aegean considers this level to be internationally competitive; Ryanair, used to regional airport charges of half than sum, does not.

Ryanair’s response was to announce the closure of its base at Chania in Crete, cutting its domestic capacity by about a third and transferring two 737-800s to Germany. However, it is maintaining its domestic Athens network on thick routes to Thessaloniki, Rhodes, Mykonos and Santorini.

Ryanair also stated that it still wanted to discuss a development plan with the airport operators that would enable it to add aircraft back into the market and operate year-round as opposed to seasonal service. And Wizz Air, with currently minimal presence in Greece, is reported to be considering expanding in this market.

Objectives

Dimitrios Gerogiannis is rather disdainful of grand strategies and long term projections. In a presentation this March, Aegean’s stated objectives for 2018-2023 were simply summarised as:

- Grow passenger volume from 13m to 15m-plus. (This seems overly modest; based on the fleet plan, 18m passengers should be targeted.)

- Increase the fleet from the current 61 (49 A320 family plus Olympic Air’s 10 ATR42s, 8 Q400s and two Dash 100s) to 75 in total. The turboprop fleet, operated under the Olympic brand, will be rationalised to one type.

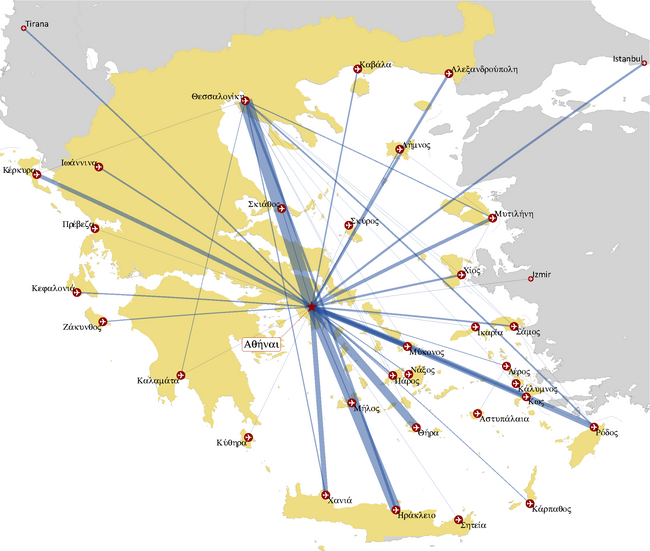

- Retain existing aircraft bases at seven (hubs at Athens, Thessaloniki, Larnaca in Cyprus plus focus cities of Rhodes, Heraklion, Chania and Kalamata).

- Increase international points served from 145 to 175, while domestic destinations remain at 30.

- Concentrate operations on Athens, where the airline can capture business travel and avoid the extreme seasonality of the Greek island market, and develop connecting flows there.

Aegean puts increasing emphasis on its role as a connecting airline. Since 2008 the number of connecting passengers at Athens has risen fivefold to 3.5m, 32% of total throughput. It identifies numerous connecting possibilities and has built a wave structure at Athens — no less than eight daily waves, though three of these are “rolling”.

AIA certainly has the facilities to deal with an expanded transfer hub, but the reality is that that Aegean’s international points to the east and south are sparse, and, given its conservative nature, the airline is unlikely to invest in these higher-risk regions. Nevertheless, Aegean will develop its hubbing operations, perhaps evolving into a niche alternative to THY’s global hub at Istanbul, which for perspective is approaching 40m connecting passengers.

Note: Analysis of scheduled international and domestic seats

Note : Olympic amalgamated into Aegean in 2012