Alaska Air and Virgin America: Regulatory, fleet and branding challenges

April 2016

Alaska Air Group’s planned $4bn acquisition of Virgin America, announced on April 4, would combine two award-winning niche airlines that have a similar focus and minimal network overlap into “West Coast’s premier carrier”. The combined airline would overtake JetBlue and become the fifth largest US airline. It would have the makings of a nationwide LCC that could compete more effectively with the four largest carriers (American, Delta, United and Southwest) that control 80% of the domestic market.

It would be the first airline merger in the US since the American-US Airways deal closed in December 2013 and the second combination involving low-fare carriers, following Southwest’s acquisition of AirTran in May 2011.

But this deal faces many potential challenges, among them an inhospitable regulatory environment, fleet dis-synergies, labour cost hikes and tough decisions about branding.

Alaska is paying a large premium for what it considers “scarce real estate” and a one-time opportunity to get a stronger foothold in California.

But Alaska will find itself in some of the nation’s most competitive markets — where, incidentally, Virgin America is achieving a revenue premium over competitors thanks to its unique blend of friendly, hip upscale service and competitive fares.

Virgin America has been a huge hit in the marketplace and enjoys a cult-like following. If Alaska does not want the expense (and potential confusion) of maintaining a dual brand, would Virgin America’s customers take their business elsewhere?

In contrast to many past airline mergers, this deal would be done from a position of strength. Both parties are earning healthy profits, have strong balance sheets and are in the growth mode. Is that a help or a hindrance?

The proposed deal

Alaska is acquiring Virgin America in an all-cash deal with an equity value of $2.6bn and an enterprise value of around $4bn. The latter includes VA’s debt and capitalised operating leases, minus cash holdings.

The deal has been unanimously approved by the boards of both companies. Alaska hopes to secure Virgin America shareholder approval by June and regulatory approval in the second half of 2016, so that the transaction could close by the year-end.

Under the terms of the agreement, Alaska is paying Virgin America shareholders $57 per share, representing a 47% premium on the closing price the day before and an 86% premium on the price on March 22, the day before news leaked out that Virgin America was considering a sale.

The premium is so high because Alaska had to outbid JetBlue, though Alaska executives have described the price as “easily digestible”, because there would be both immediate benefits and benefits “over the years and decades ahead”.

Alaska expects to finance the transaction with a combination of cash ($600m) and new aircraft-backed debt ($2bn), and it plans to slow down share repurchases in 2016 and 2017 to help fund the deal.

With cash reserves of $1.6bn at the end of March, some 92 unencumbered aircraft and an investment-grade balance sheet, Alaska can easily afford the $2.6bn payment.

Alaska Air Group is 4-5 times the size of Virgin America in terms of annual revenues, passengers and daily departures. It is one of the most profitable US airlines, earning a 23% pretax margin in 2015, compared to Virgin America’s 13%.

The two airlines have very different backgrounds. Alaska is 84 years old, though the Seattle-based group was formed in 1985 as a holding company for Alaska Airlines and regional carrier Horizon Air. San Francisco-based Virgin America was launched in August 2007 by the UK-based Virgin Group together with US investors.

But there are also many similarities. Both ALK and VA run strong operations, are known for low fares and outstanding customer service, have strong brands, are technological innovators, have strong cultures and are recognised as good employers.

The combine would have $7.1bn annual revenues (2015), around 290 aircraft (including regional types) and 114 destinations (excluding 22 overlapping cities). There would be five hubs: Seattle, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Anchorage and Portland.

The Alaska name, brand and Seattle headquarters are to be retained. However, in a nod to VA’s loyal customers and corporate contracts in San Francisco and Silicon Valley, CEO Brad Tilden said that there would also be a “strong presence in San Francisco” and that Alaska would explore using the Virgin brand, which is driving a big revenue premium at Virgin America and is much better known globally.

The decision on whether or not to retain two fleet types (Alaska operates 737s, Virgin America A320-family aircraft) is not likely for a couple of years.

The merged carrier is expected to generate $225m in annual net synergies when fully integrated — $175m revenue benefits and $50m cost synergies. One-time integration costs are estimated at $300-350m.

Because of the focus on debt funding, the transaction is expected to be accretive to earnings in year one (excluding integration costs). The synergies are expected to ramp up quickly, increasing from 30% in 2017 to 100% in 2020.

Why this is happening

Virgin America did not put itself up for sale; Alaska approached it. Alaska executives said that they had first approached Virgin America’s leadership in November 2015. Subsequently, early this year VA’s CEO David Cush reportedly contacted JetBlue’s CEO Robin Hayes about a possible combination. So, when Alaska submitted its bid in March, JetBlue had already become interested and it entered the bidding process.

The deal happened for two simple reasons: Alaska wanted Virgin America badly enough to pay a huge premium, and it was a great deal for Virgin America’s investors.

It would provide a well-deserved exit for Cyrus Capital Partners and other Virgin America initial investors, which had to recapitalise the company several times in the seven-plus years before it was able to go public in November 2014.

The bailouts were necessary because Virgin America had a tough time getting started and becoming viable. Its setbacks included a two-year delay to its launch due to questions about its ownership and control structure, a new DOT enquiry in 2009 about its US citizenship status, and difficulties in obtaining gates and slots at desirable airports.

After a recapitalisation in January 2010, Virgin America got into trouble as the result of an over-ambitious growth spurt, which led to a restructuring of its Airbus orders and a no-growth strategy in late 2012. There was another financial restructuring in the spring of 2013, in which the shareholders wrote off $290m of debt in return for future stock purchasing rights and provided an additional $75m of debt.

The backers recouped some of their investment in VA’s successful IPO but, importantly, remained on board. After the IPO, Cyrus Capital Partners and the Virgin Group held 35% and 33% stakes, respectively, though as a non-US citizen the latter is limited to 25% of the voting rights.

In a blog post, Virgin Group’s founder Richard Branson expressed “sadness” about the merger and noted that there was nothing he could do to stop it. The $500m-plus that his investment company will receive from the deal should compensate.

For the US-based investors, this could be the best time to exit Virgin America. The US airline industry may be at the peak of the cycle, and VA’s own earnings are expected to fall this year. The current consensus estimate is a 21% decline in EPS in 2016.

While Virgin America is now reporting healthy profits, its RASM is under pressure due to price wars in markets such as Dallas. Many analysts are concerned about the limited network that is heavily exposed to competition from both network carriers and ULCCs (even though so far Virgin America has fared well in competitive markets).

The main long term concern is about the extent of the growth opportunities for that type of business model, which Virgin America has described as “premium revenue generation with an LCC cost base”.

Alaska sees the ALK-VA combine falling into the broader “bleisure” segment that also includes JetBlue and Hawaiian (low-fare airlines that focus on higher-end leisure and cost-conscious business travellers). That segment accounts for 12% of US carriers' North American revenues (see chart). Alaska believes that it is a very promising and underserved segment of the market.

Alaska’s main motive for the acquisition is the expanded West Coast and California presence that Virgin America offers, which would give it an “enhanced platform for growth”. The deal would also give Alaska more access to slot-constrained airports on the East Coast.

Alaska’s leadership noted that the company is in a strong position to take on new challenges, because it is performing well in all respects. “We’re anxious to get more real estate to work with”, Brad Tilden said.

Tilden also noted that the US industry had become more concentrated, which was good for investors but also suggested to an airline like Alaska that “scale is relevant”.

And airport infrastructure constraints in the US now make it hard for airlines to grow organically. Tilden praised Virgin America for having done an “amazing job at building a network from slot-constrained airports from West to East”.

There is undoubtedly also a defensive element to the deal. It would help protect against JetBlue’s further inroads to the West, as well as more intense price matching by the legacies in the next economic downturn.

Although Virgin America is not much of a threat to Alaska (the network carriers’ hub-building moves in Seattle have posed bigger competitive challenges in recent years), it must be noted that in 2009 Alaska was the leading voice in the campaign to try to get VA stripped of its US citizenship.

California opportunity

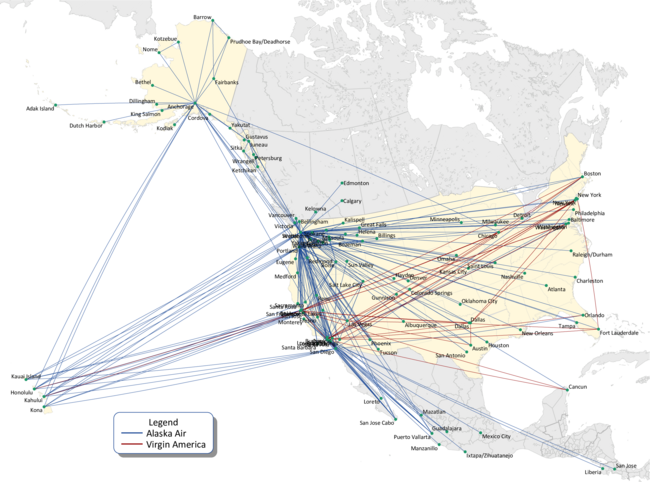

Given its size and financial success, it is a little surprising that Alaska is still a niche operator with a heavy focus on the Pacific Northwest and the state of Alaska. In 2015, about half of the group’s capacity was along the US West Coast (36%) or to/from/within Alaska (15%).

But the network has gradually broadened to include a sizable transcon/midcon component (24%) and Hawaii operations (18%), both primarily from Seattle. Alaska also serves Mexico (6%), Canada (1%) and Costa Rica (since November 2015).

Alaska has grown at a relatively brisk 7.7% average annual rate since 1995. In the past five years, it added 26 new cities and 90 new markets. Last year’s ASM growth was 10.6%.

The biggest driver behind the acquisition is the opportunity to get a solid foothold in California, which has more than three times the population of Alaska, Washington and Oregon combined (39.1m, compared to 11.9m) and 2.5 times the daily passengers.

In terms of seats offered, the ALK-VA combine would become the second largest carrier in SFO (compared to Alaska’s current sixth position) and “relevant in a very fragmented market in LAX”. Alaska would be present in SFO’s ten largest markets, compared to one currently, while in LAX the number of top-ten markets served would increase from one to eight.

The ALK-VA combine would be the West Coast’s largest carrier, with 22% of the total seats, compared to Southwest’s 21%, United’s 16%, Delta’s 12%, American’s 12%, Hawaiian’s 7%, JetBlue’s 2% and Spirit’s 1%.

Alaska hopes that such critical mass would help make the future combined loyalty programme a big success. Virgin America has a significant loyalty base in California, and many of Alaska’s current programme members are also based in that state.

Virgin America would bring to the union 23 valuable slots at JFK, as well as 12 slots at LGA and 15 at Newark. Today Alaska has only one daily red-eye to JFK and obtaining that slot pair “took at least five years”.

Alaska believes that all of that would enable it to extend profitable growth well into the future, though it would probably stick to its long-established target rate of 4-8% annual ASM growth.

The combined network would offer more connections for international airline partners out of Seattle, San Francisco and Los Angeles. Between them, Alaska and Virgin America have an impressive array of global airline partners, and Alaska also has two-way codesharing with Delta and American.

Financial strength

Alaska Air Group has now achieved double-digit operating margins for six years in a row. Last year it earned operating and net profits of $1.3bn and $848m, respectively, on revenues of $5.6bn. According to Alaska’s presentation, its 24% 2015 pretax margin compared with the US LCC group’s 18.8%, the legacies’ 13.9% and the S&P Industrials’ 13.1% margin.

After heavy losses up to and including 2012, Virgin America has now had three profitable years. In 2015 it earned adjusted operating and net profits of $212m and $202m, respectively, on revenues of $1.5bn. Pretax ROIC was a respectable 17.9%. The results have improved due to RASM outperformance, reduced lease and interest expenses post-IPO, and of course lower fuel prices.

Virgin America began growing again in the second half of 2015, as it resumed taking A320 deliveries. This year’s ASM growth is projected to be around 15%, though about half of the new capacity will go to the Hawaii market that VA entered in November.

It makes sense for Virgin America to grow because it is still a young airline, but the brisk rate will make it hard to improve from the position at the bottom end of the US airlines’ profit range.

Alaska has been the industry’s financial leader in many respects. It was the first airline in the US to start managing to ROIC (25.2% in 2015). It began reducing leverage early and has slashed its debt-to-capital ratio from 81% in 2008 to 27% in 2015. It was the first US airline in the post-2001 era (other than Southwest) to secure an investment grade credit rating.

Alaska has also paid down its pensions and led the process of returning capital to shareholders. The $6.1bn of cash flow generated in 2010-2015 was used as follows: $3bn for fleet and other capital investments, $1.2bn for debt reduction, $1.4bn to reward shareholders via dividends and stock repurchases, and $500m for pension contributions.

So Alaska seems well-positioned for the Virgin America acquisition. The investment grade balance sheet will enable it to finance the $2bn debt component at very attractive rates. Alaska has not been in the market for aircraft financing since 2009 and apparently there is tremendous interest in financing the proposed transaction.

The deal would weaken Alaska’s balance sheet, though; it was indicative that Fitch and S&P immediately put Alaska’s ratings on review for a possible downgrade. But Alaska believes that its debt-to-capital ratio would only rise to 58%, and it would aim to reduce it to 45% by 2020. Alaska also expects to resume share repurchases at the current level in 2018.

Synergies and dis-synergies

According to Alaska’s presentation, the $225m net synergies, at 3.1% of combined revenues, are in line with prior mergers such as Southwest-AirTran but substantially lower than some of the biggest deals (see chart). The revenue synergies would come from network connectivity, “mixing and matching” aircraft and opportunities with the company-branded credit card.

However, at least one Wall Street analyst, JP Morgan’s Jamie Baker, immediately said in a research note that he expected the synergies to be lower. Baker’s “first pass” estimate on April 4 was $175m total synergies ($150m/$25m).

Baker cited an “inhospitable regulatory environment”, which could lengthen the approval process. He noted that in consolidation labour costs usually escalate and that there were “no money-losing hubs to close or expensive airport real estate to consolidate”. He noted that it was best to start from a basis of fleet commonality, “lest potential synergies end up being allocated to aircraft lessors and/or aircraft OEMs in pursuit of simplification”.

Regulatory approval is clearly the big wild card. On the one hand, there is little network overlap and the intention is to grow. But the reality may prove different. The DOJ is known to be unhappy about the latest round of airline mergers, which have led to a high concentration in the industry.

A dual 737/A320 fleet is potentially a problem in a merger of two low-cost carriers. Either aircraft type would be perfectly suited for the combined network. But Alaska is a longtime Boeing customer, so if it opted for a single-type fleet, Boeing would probably win.

There is much flexibility around the Virgin America fleet, because substantially all of it is leased and the leases start expiring in 2020. Some 25 aircraft could be returned by 2022. VA is due to take 10 A321neos from GECAS in 2017-2018 but could probably get out of that commitment. And VA’s order for 30 A320neos for 2020-2022 delivery apparently has a “favourable cancellation provision”.

But Alaska said that it plans to get to know the A320 first. Interestingly, its regional unit has just opted for a second fleet type. On April 12 Horizon Air announced a $2.8bn order for up to 63 E175s, which will supplement its Q400 turboprop fleet (though the E175 and Q400 are for different types of markets).

Labour integration is normally a challenge in airline mergers. At this stage, all looks good. VA’s workers would join another well-run company that takes good care of its employees. Alaska’s key unions have publicly welcomed the deal — the growth opportunities probably made it an easy sell.

It always gets more complicated when the time comes to sort out the details. In this case, the two different fleets could cause problems. As Baker pointed out, there is no existing A320 rate in the Alaska pilot contract, and in the past 737 pilots have required incentives to cooperate. Baker envisions a gross labour dis-synergy of $100m inclusive of all work groups.

While the customers and loyalty members of both airlines would benefit from the broadened network, ALK and VA have different approaches to customer service, and their customer cultures are very different. Seven out of Virgin America’s top-ten corporate customers are Silicon Valley-based tech companies.

Alaska focuses more on the airport experience and Virgin America on the on-board experience. One frequent flyer with both airlines interviewed by The Wall Street Journal described Alaska’s FFP as “far superior” but said that there was no substitute for Virgin America’s in-flight experience, which was “flying like a king”.

Combining those approaches would be a certain winner, and Alaska has said that it would study the Virgin brand and customer experience. Alaska considers the royalty payment that VA pays to the Virgin Group (0.7% of annual revenues) “not huge in the grand scheme of things”, so perhaps there is potential for a new licensing agreement to be negotiated.

In reality, though, maintaining two brands would be expensive and potentially confusing to passengers, so the combine will probably gravitate towards Alaska’s more basic in-flight experience.

The key question is: how would Virgin America’s passengers respond to the disappearance of the brand that they love? Would they take their business to other airlines in highly competitive markets such as the transcon?

In the meantime, JetBlue has moved fast to announce plans to expand its highly successful Mint premium product to more transcon markets, including Las Vegas, San Diego, Seattle and Ft. Lauderdale from early 2017. JetBlue said that it wanted to “capture opportunity to introduce new transcon competition for customers facing fewer options”.

| Alaska Air | Virgin America | acquisition | |

| Net Current Assets | (143) | 109 | (600) |

| Fixed Assets | 4,870 | 1,042 | |

| Goodwill | 1,792 | ||

| Total Assets | 4,727 | 1,151 | 1,192 |

| Debt | 571 | 259 | 2,000 |

| Other liabilities | 1,745 | 84 | |

| Equity | 2,411 | 808 | (808) |

| Capital Employed | 4,727 | 1,151 | 1,192 |

| Off balance sheet debt† | 840 | 1,758 |

Source: Company reports. Note: † at 8x aircraft rentals

| 204 | (99) | 61 | (32) | |

| Alaska Air Group | Virgin America | |||

| In service | On order | In service | On order | |

| 737 Classic | 26 | |||

| 737 NG | 126 | (29) | ||

| 737MAX | (37) | |||

| A320 | 61 | (2) | ||

| A320neo | (30) | |||

| Q400 | 52 | |||

| E175 | (30) | |||

Source: Ascend. Note: Virgin America also has a commitment to lease 10 A320neos from GECAS 2017-18.

Source: Alaska Air Group presentation (April 2016)

Source: Company Reports

Source: Company Reports

NORTH AMERICAN

REVENUE SHARES

Source: Company presentation