TAP Portugal up for sale again

April 2015

Despite reporting a large net loss in 2014, TAP Portugal has again been put up for sale by the Portuguese government. As it celebrates its 70th anniversary, will Portugal’s flag carrier find a new owner this time around?

The Portuguese state — which has always owed 100% of TAP — previously tried to privatise the airline in 2011 (see Aviation Strategy, June 2011), but without success. After receiving 12 offers of interest, the only firm bid the state received was from Polish/Brazilian businessman German Efromovich, whose Brazil-based Synergy Group owns a majority of Avianca Holdings (which controls the Avianca group of airlines). But this was turned this down after the government criticised the bidder’s apparent inability to provide adequate financial guarantees. Sources indicate that Efromovich offered €35m in cash for the airline, plus a €316m injection into the balance sheet as well as the assumption of the airline’s €1.1bn debt.

The latest plan to offload the airline was announced in November 2014, with the state aiming to sell 66% of its stake, with 61% going to investors and 5% reserved for TAP’s 7,500 employees (at a discount to the final sale price). The state says it may also sell its remaining 34% in the future, at no earlier than 24 months after the sale of the first tranche, though of course that’s dependent on getting the first away successfully — which will be no easy task.

Conditions for a sale are, if anything, worse for TAP this year than they were back in 2011. After posting a €20.1m net loss in 2012, in 2013 TAP posted a 1.9% increase in revenue to €2.7bn, with operating profit up 8.1% to €44.1m and the net loss coming down to €1m. In 2014, however, while revenue rose 1.1% to €2.7bn, the operating profit plunged 94.3% to just €2.6m, with the net loss increasing 93 fold to €80.1m.

TAP blamed the results on various causes — the World Cup in Brazil in June and July (when the airline said that no-one wanted to leave the country, preferring to stay at home and watch the tournament instead), the late arrival of new aircraft, 22 days of strikes through the year and “operational issues” which, combined, took €108m off the bottom line. The strikes alone cost more than €25m, the airline claims, and one of the key problems facing any acquirer is management’s relationship with its workforce, which is poor.

TAP’s unions are vehemently opposed to the sale of the government’s stake, which they argue will only lead to redundancies and cuts in pay and conditions. But after a coalition of 12 unions representing the workforce threatened to strike for four days over the Christmas holiday period as a protest against the sale, the government backtracked and said it would impose a strict condition upon any acquirer whereby they couldn’t make any mass lay-offs once they acquired TAP.

30 months moratorium

According to the terms of that agreement signed between the government and TAP’s unions in January, there will be a 30-month moratorium on collective redundancies or for as long as the state remains a shareholder. Another agreed pre-condition of a sale (there are nine major ones in all) is the full implementation of all existing collective bargaining agreements between unions and TAP, as well as maintaining TAP’s status as the Portuguese flag carrier, preserving the company headquarters and main hub in Lisbon, as well as “effective management” remaining in Portugal.

Those conditions will be a major stumbling block for investors, who are likely to want to make cost savings and at least trim the existing TAP workforce, but they are not insurmountable; if the price were right, an acquirer would wait the 30 months before making the necessary cost rationalisation.

TAP states that it has already cut €250m from its cost base over the last three years, and the airline is in the last two years of a 2012-2016 strategic plan that has three goals — network growth, unit cost improvement and unit revenue increase.

That is a fairly generic set of objectives, and any purchaser would look very closely at the underlying cost structure of TAP, and particularly at the network structure and strategy. The Portuguese domestic market is small by any European standard (around 70% of TAP’s revenue is generated outside of Portugal) so in effect the airline’s strategy depends on interconnecting passengers at the Lisbon hub from Africa and Brazil to and from Europe.

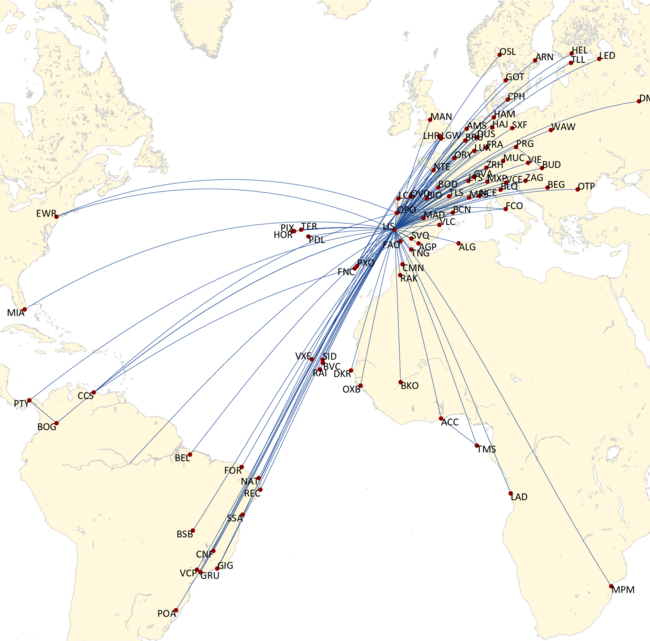

TAP carried 11.4m passengers in 2014, 6.6% higher than in 2013, with a 30:70 split between long- and short/medium-haul passengers. TAP currently operates to 84 destinations in 35 countries, across Europe, Africa, North America and South America, with the largest route network being in Europe, with nine cities served in Portugal and 44 in the rest of Europe, within which Spain is the most important market, with eight destinations, followed by France, with seven, and Germany (six).

In 2014 Europe accounted for the largest proportion of TAP’s turnover — at 38.4% — but the South Atlantic market was close behind, providing 34.4% of revenues (of which the vast majority comes from the Brazilian market) and certainly a much higher proportion of overall profit

Faced with extensive LCC competition, most of TAP’s European routes are loss-making, but a reasonable European network is necessary in order to attract feed into/onto its long-haul routes, which are the profit-drivers of the airline. But this brings TAP into competition with the much bigger and efficient (and higher yielding because of a higher proportion of business traffic) hubs operated by IAG, AF-KLM and Lufthansa. The Superconnectors’ hubs in the Gulf are also filtering off connecting traffic from what were strong Africa-Lisbon routes.

On long-haul TAP serves 15 African destinations (including former Portuguese colonies) plus three in central and North America (Panama City, Miami and Newark), and 13 in South America. 11 of the latter market are to Brazil, which with 84 flights a week clearly is the key market for TAP. The airline’s traffic flows between Portugal and Brazil depend on the business market both ways, the VFR market from Brazil to Europe, and holiday traffic to Brazil.

From its Lisbon hub to Brazil, TAP enjoys a monopoly on every route as Latam, which absorbed the failed flag-carrier Varig, has not replaced Varig’s services. Latam is concentrating its Atlantic operations on the north European hubs, but it will surely add Lisbon to its network in the medium term.

TAP, remarkably, says it has ambitions to fly to Asian markets (which it has served in the past) as well as the Americas and Africa, but is constrained by its fleet. The fleet totals 61 aircraft. comprising 21 A319s, 19 A320s, three A321s, 14 A330s and four A340s. In addition, its regional subsidiary, PGA (Portugalia Airlines), operates eight Embraer 145s, six Fokker 100s and two ATR 42-600s on domestic and international routes from its base at Lisbon and a secondary hub at Porto.

The only aircraft on order for TAP are 12 A350-900s, which will start arriving in 2017 and all be delivered by 2020, to replace A330s and A340s and to underpin growth on long-haul. The A340s will be the first to leave the fleet, followed by the older A330s (although most of the A330s are newer models), but it’s only once the A350s arrive that the airline can expand its long-haul operations.

TAP’s A320s (a type TAP is happy with) have an average age of 14 years and a replacement fleet also needs to be ordered for these, but TAP simply doesn’t have the finances necessary for a new order, and clearly the decision will not be made this side of a new investor coming in.

Deep pockets needed

But rationalising a European network and examining the cost base will not be the only challenges that a new owner will face. TAP also has debts of around €1bn ($1.3bn), and of course the airline can no longer be propped up by a state injection of capital. The government is clear as to what its priority is, with Sergio Monteiro, Portuguese transport minister, saying that "the state does not intend to obtain financial gains from this privatisation; rather it wants to guarantee that TAP is adequately capitalised".

Originally TAP’s privatisation was just one part of a mandated sale of state assets that was imposed on Portugal as a condition of a massive EU, European Central Bank and IMF bailout signed in May 2011, when those institutions provided €78bn of financial assistance over a three year period ending May 2014 in order to help the country out of its economic troubles. Conditions included a series of tax increases and cost-cutting programme in order to reduce Portugal’s budget deficit, the latter including privatisation of national assets — and TAP Portugal was at the top of that list.

Over the last four years more than €9.4bn has been raised from sales of stakes in energy companies, banks and other state entities — substantially more than the €5.5bn target given to the Portuguese government for the sale of assets. However the government still wants to sell off TAP, as it wants to offload the airline’s debt and find someone able to fund the airline going forward. Or, as Fernando Pinto, CEO of TAP Portugal, puts it — getting rid of majority government ownership will give the airline “more liberties”.

Government sources indicate that this time around the state is looking for a minimum of €300m in cash and investment in the airline (on top of the assumption of debt commitments) — which is some €50m less than Efromovich offered in 2012.

There is no official timetable for the latest privatisation attempt, though the government says it ideally wants to select a preferred investor by the end of the first half of 2015, with an unofficial deadline of May 15th for binding bids from interested parties.

Monteiro says that the government “is more optimistic now and we face this process with redoubled confidence that it will be successful — though we will only know when we receive the formal proposals". But complicating the process is substantial opposition to the move, not just from unions but from a significant part of Portuguese society as a whole. The upcoming general election in Portugal (being held in September and October) puts the sale even more at the forefront of the news pages, and the centre-right government’s is facing intense opposition from the main opposition, the Socialist Party (PS) which opposes the plan to privatise TAP.

PS argues that a sale is no longer needed for bailout reasons, and that TAP is "one of the pillars of national sovereignty" as it connects Portugal with its interests in South America and Africa, with PS instead suggesting that the state should IPO a minority part of TAP while retaining a majority stake in the flag carrier. To add to the mix a number of Portuguese celebrities have recorded video messages attacking the government’s sales, and the Pilots’ Union has now announced another strike protesting against the privatisation, to run from May 1st to May 10th (and which will severely affect TAP’s operation even after a “minimum services” provision that will be set by an arbitration tribunal and which the union will have to adhere to).

The usual suspects?

Against this background, who will step forward and make a concrete offer? The usual potential buyers have been mentioned in the Portuguese press — the Gulf super-connectors (though of course investors from outside the European Union couldn’t acquire a majority stake), IAG, Lufthansa, Spanish group Globalia (which owns Air Europa), US/Brazilian entrepreneur David Neeleman (who founded JetBlue in the US and Azul in Brazil) and German Efromovich (yet again), as well as a number of Portuguese entrepreneurs that include Miguel Pais do Amaral, who reportedly may bid jointly with Frank Lorenzo, former chairman of Continental Airlines.

If it has a choice (and that’s a very big if), the government will choose an airline investor who has the very deepest pockets — but there are not too many of those candidates around.

A bid from International Airlines Group might make some strategic sense, as a combination of the Lisbon and Madrid hubs would provide IAG a with a dominant grip on traffic flows between South America and Europe — although that’s something that regulators would be concerned about. It might be more logical for IAG to wait and see if an independent investor can start to turn TAP around, then make a move.

Etihad’s deep pockets would make a deal relatively easy to finance and the Abu Dhabi carrier already operates a codeshare with TAP across the South Atlantic and there might be aeropolitical advantages.

Lufthansa might be tempted. TAP joined the Star alliance in 2005 and has codeshare deals with many Star members, while TAP’s Lisbon gateway into South America could be developed into an alternative to oneworld’s Madrid hub.

Reports from Portugal, however, suggest that TAP’s management would prefer not to be acquired by a large rival of the size of BA, Lufthansa or Qatar, as it would then be subservient to the managerial experience of the larger and more efficient acquirer. But that’s the key point of the deal — to bring in better, more ruthless management that can do away with many of TAP’s inefficiencies, and make the tough decisions over routes, fleet and workforce that a state-owned TAP has avoided for far too long.

| Total | 75 | 12 | 90 |

| In Service | Orders | Total | |

| A319 | 21 | 21 | |

| A320 | 19 | 19 | |

| A321 | 3 | 3 | |

| A330 | 14 | 14 | |

| A340 | 4 | 4 | |

| A350 | 12 | 15 | |

| 100 | 6 | 6 | |

| ERJ-145 | 8 | 8 |