Etihad's European strategy - the new Realpolitik

April 2015

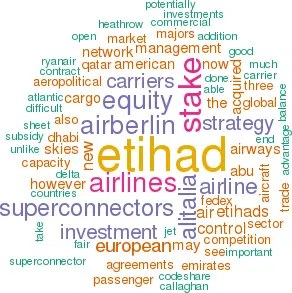

Etihad in the past few years has pursued a strategy that has been likened to the “Hunter Strategy” of the former SAir Group (the airline formerly known as Swissair) in the late 1990s. It has acquired minority stakes in moribund airlines which without this investment would normally have been expected to fail. Commentators have tried to explain the moves as an attempt to form a fourth global alliance, to generate operational synergies directing feed to its Abu Dhabi hub; or as providing Etihad (the smallest and youngest of the Superconnectors) with a method of competing efficiently with its close cousin Emirates (now the largest carrier worldwide ranked by international RPK). These interpretations may be partly correct, it is becoming clearer that Etihad is cleverly positioning itself in the emerging Realpolitik of the global aviation industry.

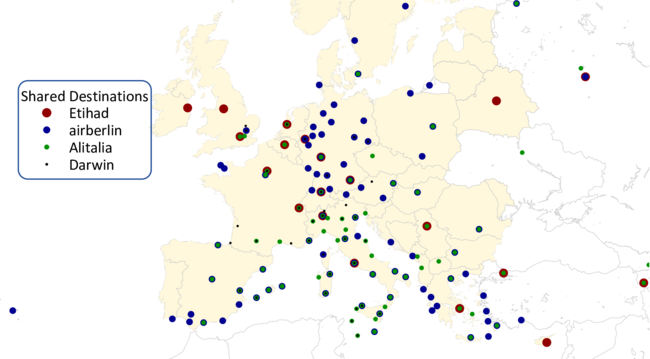

Firstly, a review of Etihad’s investments; in 2011 Etihad acquired an equity stake of 29% in airberlin — Germany's second largest scheduled airline — for which it paid €75m. It subsequently acquired a 70% stake in airberlin's frequent flyer programme (topbonus) for €175m, subscribed to a €300m perpetual 8% convertible bond and provided a medium term loan facility of €225m. airberlin currently has a market capitalisation of €140m.

The perpetual convertible is an interesting vehicle that has been used by others (such as Wizz Air — see Aviation Strategy March 2015) to get round ownership rules. For accounting purposes it goes on the balance sheet as “equity” but voting rights legally do not accrue until shares are vested on conversion. Potentially, were this loan ever converted, Etihad would have an equity stake of over 70% in airberlin.

At the end of 2014 Etihad finalised its investment of a 49% equity stake in a new Alitalia — Società Aerea Italiana to take over the good bits from the dying Alitalia — Compagnia Aerea Italiana (which in turn had acquired the good bits of the bankrupt Alitalia — Linee Aeree Italiane in 2008). For the equity stake it paid €387.5m. In addition it bought five slot pairs at Heathrow from Alitalia for a reputed €60m to lease back to the Italian operating company and took a 75% stake in Alitalia's FFP MilleMiglia for €112m.

More minor investments in Europe have involved the acquisition of a 49% stake in Air Serbia (with a five-year management contract) and a 33% stake in Swiss regional airline Darwin (subsequently rebranded as Etihad Regional).

Meanwhile Etihad has also acquired a 24% equity stake in Indian carrier Jet Airways for $379m (with the sweetener of $70m for the acquisition of three slot pairs at Heathrow leased back and a majority of the Jet Airways FFP for another $150m). In addition it has been gradually increasing its stake in Virgin Australia — now with 24% equity involvement it is vying with Singapore Airlines and Air New Zealand for effective “control” of the Australian contender to Qantas. In addition it has a 40% equity investment and a five year management contract in Air Seychelles and built a 3% equity stake in Aer Lingus.

Alliance unlike any other

The Etihad alliance is unlike any of the other Global Alliances. Etihad, while on the face of it a minority investor in its partners, is a majority provider of capital, and effectively in control. It has main board representation and has parachuted senior management into the companies in which it has invested. Apparently there are senior management meetings every couple of months to discuss strategy; although so far there does not seem to have been a great progress in creating real synergistic benefits.

There has been some rationalisation — to align all operators on a common distribution platform, coordinate IT, purchasing power. There have been swaps of aircraft between operators (A320s from Alitalia to airberlin; 777s from Jet Airways to Etihad), and steps to combine the frequent flyer programmes into a single entity. Apparently one of the main targets from James Hogan, CEO of Etihad driving the strategy, is to align quality control particularly for in-flight cabin service (although it is difficult to imagine that the draconian control over the non-unionised Etihad ex-pat cabin crew could be accepted in Berlin or Rome).

There may be some network synergies. Both airberlin and Alitalia are developing routes to and through Abu Dhabi. airberlin had successfully applied for and operated code-share flights with Etihad from the Luftfahrt-Bundesamt (LBA) but was dealt a blow from the regulator last Winter when in a sudden U-turn its code-share application for the season was denied. Darwin, rebranded as Etihad Regional, may be able to provide some modest feed onto Etihad's network. Code-share agreements between Alitalia and airberlin however are probably of very limited use. Etihad has claimed that the marginal additional revenue achieved from the airberlin link has already repaid the original investment.

CEO James Hogan, an astute manager, avers that the investments are done on a distinctly commercial basis. Unlike Swissair 20 years ago, it is not hunting out of desperation. There is a possibility that its highly experienced management team will be able to turn round airberlin and Alitalia. In the meantime it is effectively guaranteeing some 15,000 jobs directly (and a multiple of that indirectly) in a politically highly sensitive sector and starting to make itself as important a player in European airline operations as the Superconnectors collectively have done with their massive aircraft orders to the aircraft manufacturers in Seattle and Toulouse.

The investment strategy by Etihad could therefore be regarded as aeropolitical, a defence against the regulatory backlash that Etihad and the other two Superconnectors are facing in Europe where the Commission is in the process of investigating the question of effective control of European airlines by non-EU nationals. While looking at Etihad's involvement in airberlin and Alitalia, it is also considering Korean Airlines' investment in Czech Airlines and Delta's 49% stake in Virgin Atlantic. In the US there has been an intensification of the high-profile lobbying of the Administration to take action to curtail the Superconnectors.

Etihad vs the US protectionists

At a conference on this subject, organised by CAPA at the end of April, Etihad’s Legal Director, Jim Callaghan, found himself the sole Superconnector representative ranged against silver-tongued attorneys from Delta and American, this time allied with Lee Moak, ex-president of ALPA and now fronting “Americans for Fair Skies”, a body which claims that that it support Open Skies but thinks that the consequences of the US-UAE and US-Qatar Open Skies agreements are outrageous.

The Fair Skies message is robustly populist. Its website proclaims: “What US policy makers did not envision, however, is that emirs and sheiks and their authoritarian governments would use this as an opportunity to manipulate the understandings and agreements established under Open Skies to undertake a sustained effort to steal our passengers and threaten the entire viability of our airline industry and the tens of thousands of Americans it employs”.

By contrast, the rhetoric from the US carriers was fairly restrained — they said that they weren’t attacking Etihad or Emirates or Qatar Airways themselves but contended that their complaints were to be seen within the context of a trade dispute between the US and the Middle East countries. This seems to be a lawyerly distinction — basically they argued that government subsidies were behind the rapid expansion of the Superconnectors across the Atlantic, forcing them to contract, and to nearly abandon important markets like India; this was unfair competition and that the US government should put a hold on new services from the Superconnectors, specifically capping capacity into the US at January 2015 levels, until the subsidy issues were resolved. According to Delta, this will be when “the US stems the flow of subsidised capacity to the US”.

This view horrified the representative of the US travel and tourism industry who saw the recent gains in inbound tourism being undermined by protectionist actions — what about Orlando, its hotels, restaurants and DisneyWorld, which are to be connected to the Emirates network with a new daily service starting in September?

It also revealed a profound split between the US passenger airlines and the cargo business. FedEx pointed out that it and UPS combined employed three times the number of people as the big three US carriers, and it operated a very successful cargo network at its Dubai hub hugely outcarrying the Superconnectors in terms of freight tonnage and the US passengers airlines in terms of flights. The US passenger airlines’ trade dispute was potentially a serious threat to FedEx, and it was not at all impressed by American saying that cargo could be excluded from the complaint. The US position would then be presented as: cargo excluded as the US has a competitive advantage, passenger traffic only to be considered as the US has a competitive disadvantage.

The FedEx attorney also introduced a wider concept to the aeropolitical argument. Trade agreements for the cargo integrators are not just about the allocation of flying rights between two countries; they encompass, as is normal in most industries, “equal national treatment”. Basically this allows FedEx or UPS or DHL to operate distribution centres and fleets of trucks in foreign countries beyond the entry airport. The passenger airline equivalent would be cabotage, a concept that causes an apoplectic reaction in US major carriers, their unions and most politicians.

Back to Jim Callaghan of Etihad: he managed to draw a parallel between the attack from the US Majors and the abuse Ryanair, his previous airline, was subjected to by the European incumbents. Equating Etihad with Ryanair might be a stretch, but he did allude to what we consider to be a real issue. The US majors with their European partners have oligopolised the North Atlantic, maybe they have monopolised it, as the market has clearly been divided up into Star, SkyTeam and oneworld zones of control. In this context the encroachment of the Superconnectors in this super-profitable sector appears intolerable, even though their current North American capacity share is only about 2%.

The US majors the have some difficult questions to answer (which they completely failed to in the conference). If the Superconnectors were forced to freeze or reduce their capacity to the US, would the US airlines be willing or able to fill the gaps? What prices would they charge? As Callaghan pointed out, the relevant unfair competition clause in the US-UAE and other bilaterals refers to predatory pricing, and no case has been made for that. In effect, the Delta and American were reduced to whingeing that they couldn’t compete with the Superconnectors in India, potentially the second most important growth market after China.

How much subsidy then?

Nevertheless, Etihad had to address a tricky question: how much does the Emirate of Abu Dhabi subsidise its airline? Research commissioned by the US carriers suggested $14bn out of a total of $40bn for the three Gulf carriers. Callaghan’s response was in essence that; the balance sheet amounts that had been categorised as subsidy was the totality of Abu Dhabi’s equity investment in the carrier.

This is where things get complicated. Is Etihad’s situation analogous to the European flag carriers in the 1970s and 1980s whose governments poured in subsidies for political reasons or, to put it more positively, to enable commercial turn-around plans? Or is a rational investment in a national carrier by an oil rich state planning for a diversified future?

For perspective, the population of the UAE is about 9m (only 1.4m are Emirati citizens), less than 3% that of the US. In such tiny states it is impossible to know where the political world end and where the commercial sector begins (indeed in difficult to distinguish in much larger companies), However, it could reasonably be argued that what Abu Dhabi, Dubai and Qatar have done is invest in a sector where they have a comparative advantage, which is the economic basis for the benefits of free trade (see Adam Smith, David Ricardo, etc). And that comparative advantage comes from the geographical position of the hubs, the 24 hour operations, the new aircraft, the tax regime and the non-unionisation of the workforce. In the present global market, the Superconnector model is the most efficient for inter-continental traffic, and the old but persistent idea of fair bilateral competition simply does not apply.

Ambiguous Europeans

The American Airlines attorney was asked about its oneworld partner IAG which clearly strongly opposes the US carriers’ complaint. “Disagreement among close friends”, was the muted reply. However, the fact that BA is saying that Superconnector competition is a “good thing” is very significant. IAG, of course, is now 10% owned by Qatar Airways and the Qatar state investment fund has a sizeable 20% stake in Heathrow Airport.

European airlines do not have a unified aeropolitical response to the Superconnectors in general or Etihad in particular, and cannot form a united front with the US Majors. Alitalia and airberlin has followed BA and Iberia in exiting the Association of European Airlines (AEA) which appeared to be supporting the US carriers’ compliant. The AEA’s aeropolitical power has now been emasculated.

Lufthansa is in a dilemma. It has complained at length about Emirates (which has limited access into Germany itself but can bypass Frankfurt) and the undermining of its network by THY (with no such restrictions) into the hinterland behind its hubs. However, it probably prefers to have airberlin as a weak competitor in a “comfortable duopoly” rather than see it fail and see Ryanair or easyJet expand further in the domestic market.

Even Air France/KLM may be becoming a little ambiguous, as its poor financial performance and weakened balance sheet may soon require support from an investor with a deep pocket. As Michael O’Leary has rudely suggested, Air France’s ultimate strategy should be to de-merge KLM and seek a Middle East airline partner willing to take a substantial equity stake.

Note: From various sources.