Aeroflot: Advantages and disadvantages of state control

April 2011

Of all of the major European airlines, Aeroflot has perhaps been the least affected by the recession of the last couple of years and is on course to report significant profits for 2011. But can the Russian flag carrier act as commercially as it wants to given continuing state control – both in terms of equity and pronouncements by the Russian prime minister on what Aeroflot should do?

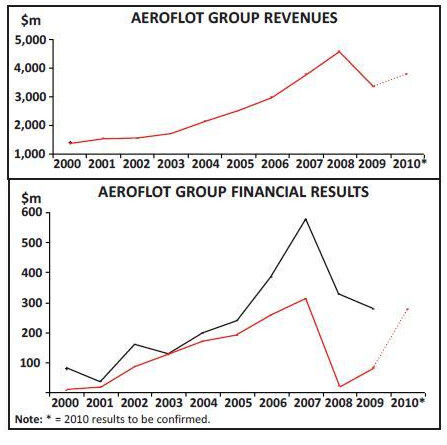

Moscow–based Aeroflot operates to approximately 100 destinations in 50 countries around the globe and as can be seen in the graphs (see page 16) posted a steady rise in revenue and profits through the 2000s — and even when recession struck the airline continued to record significant operating profits and keep its net figures in the black.

In late March Aeroflot director general Vitaly Saveliev (who has been in the post since April 2009) told a government meeting that Aeroflot would report a substantial improvement in its financial results for 2010, with revenue rising 14% to $3.8bn and net profit reaching $280m, compared with $86m in 2009 (all figures under IFRS), thanks to cost–cutting, revenue growth and more stable oil prices.

Russia’s Otkritie Bank considers these preliminary figures to be “neutral”, since the revenue total is less than the previous Bloomberg consensus figure of $4.1bn but the net figure is higher than the Bloomberg consensus of $203m. Otkritie points out that “the reliability of the published data cannot be verified yet”, particularly as the forecast 2010 figures are hardly changed from the actual results Aeroflot posted for the first nine months of 2010, when it had net income of $281m. The actual 2010 results will be released in May.

Nevertheless, the known figures for the first nine months of 2010 are impressive, and the net profit figure of $281m would have been far higher but for losses in certain parts of the Aeroflot group. Specifically, while the mainline and cargo operation made a $350m net profit in the first nine months of 2010 (with Aeroflot–Cargo reducing its losses in the first nine months of 2010 to $7m, compared with $42m in January–September 2009), the OJSC Terminal subsidiary (which operates Terminal 3 at Sheremetyevo) made a net loss of $56m.

Strategic refresh

Against that background of solid financials, at the end of 2010 Aeroflot unveiled a new strategic plan for next 15 years, adopting an explicit goal to grow its share in the Russian domestic and international aviation markets to 2025. In a speech given to the Moscow aviation hub in March, Saveliev says the airline aims to carry between 70m and 74m passengers in 2025, with a quadrupling of the company’s current revenues compared with today. He added that Aeroflot’s goal is to have a 40% share of the international market to/from Russia in 2025 and a 60% share of the domestic market.

Those are ambitious targets. Aeroflot carried 11.3m passengers in 2010, of which 4.2m were domestic passengers and 7.1 international.

Though the domestic total was up 25% on 2009, Aeroflot is keen to secure a much greater share in the large domestic market again, both in terms of being a large revenue generator in its own right as well as in terms of feeding more passengers onto international services. Or as Saveliev puts it: “We believe that Aeroflot can become a global winner only after having become a national champion.”

In the first nine months of 2010, 92% of Aeroflot’s revenue came from scheduled passengers, with 40% of that revenue coming from domestic passengers, 34% from European passenger traffic, 18% from Asia, 4% from North America and 4% from other regions. That split should change substantially as the emphasis kicks in on domestic expansion rather than international point–to–point.

At present Aeroflot has a clear lead in the international market, where its main competitor is Moscow–based Transaero, which operates 58 aircraft (all but two of which are Boeing models) on more than 100 routes in Russia, Europe, Asia, Africa and North America.

Aeroflot has also just regained a lead position in the domestic market, just ahead of the Domodedovo–based S7 Group, which has 32 aircraft (all Western models) and with 37 on order. However, Aeroflot’s market share will improve dramatically once the domestic consolidation plans unveiled by the Russian government in February last year are completed.

These entail the incorporation into Aeroflot of six airlines controlled by state–owned corporation Rostekhnologii, which are: Kavminvodyavia (KMV), Orenair, Rossiya Airlines, Sakhalinskiye Aviatrassy (SAT), Saravia and Vladivostok Air. This is to done through a two stage process, with the five smallest airlines first merging into Rossiya, and then Rossiya subsequently merging into Aeroflot. Both stages are expected to be completed later this year.

Pre–absorption of the other airlines, St Petersburg–based Rossiya has a fleet of 30 aircraft, of which 15 are A320–family aircraft and nine are Boeing aircraft, and last year it carried 3m passengers. Between them the other five airlines will add 83 aircraft to the Aeroflot group fleet — of which just 15 are Western models.

This development has had an immediate implication elsewhere in that Aeroflot has just sold its northern Russian subsidiary, called Nordavia. Previously called Arkhangelsk Airlines and dating back to the 1960s, Aeroflot took a 51% stake in 2004 and renamed it as Aeroflot–Nord before another change of brand in December 2009, to Nordavia. Nordavia currently operates a fleet of 21 aircraft, the majority of which are older–model 737s, and flew 1.4 million passengers in 2010.

Aeroflot acquired the remaining 49% of the airline (held by state–controlled Aviainvest) in the third quarter of 2010 and it had been reported that Aeroflot briefly considered merging Nordavia with Rossiya, but over the last few years Aeroflot has taken considerable trouble to untangle the operations of its two main feeder airlines (one serving the north of Russia and one serving the south) from the mainline operation. Though this allowed the two airlines to develop individual brands and strategies (while still code–sharing with Aeroflot) it also gave Aeroflot the option to dispose of them if needed.

That option has now been taken with Nordavia, which not only racked up reported net losses of $9m in the first nine months of 2010 but — more importantly – has $200m of debt (which includes long–term debt and all future lease payments on aircraft) that sits uncomfortably on the Aeroflot group balance sheet. Conveniently the Rossiya deal gave Aeroflot an excuse to offload Nordavia, since the two airlines compete against each other in the north–west of Russia, and so in March Aeroflot agreed a deal to sell Nordavia to Norilsk Nickel, a Russian mining conglomerate.

Though Norlisk was reportedly the only bidder for Nordavia it does already own a small airline called NordStar, which operates six 737–800s domestically but which has just received permission to operate international services to China, Azerbaijan and Tajikistan.

The plan is for Nordavia to merge with NordStar, which would propel the merged carrier into the top 10 Russian airlines, and then launch a raft of new domestic services out of Norilsk. Unsurprisingly the mining company is paying just $7m for Nordavia as it comes with that $200m of debt – which will now disappear from the Aeroflot books.

For the moment Aeroflot appears more committed to its other major subsidiary, Donavia, which is based in Rostov–on–Don in the south of Russia. Donavia has origins that date back to 1925 but was taken over by Aeroflot in 1993 under the name Donavia Airlines before becoming Aeroflot–Don in 2000, when Aeroflot acquired 100% of its shares.

However, after the crash of an Aeroflot–Don aircraft in Perm in 2008 Aeroflot separated out the airline, and in 2008 the name changed backed to Donavia. It now operates a mixed fleet of 16 aircraft to Europe, Africa and the Middle East as well as domestically.

Donavia lunched routes to Istanbul from four Russian cities in its winter 2010/2011 timetable and the airline is eager to launch new international routes, while domestically Donavia has gradually withdrawn from scheduled feeder routes into Moscow and now is 100% focussed on the south Russian market.

In the first–half of 2010 Donavia broke–even at a net level, compared with a net loss of $3.2m in January–June 2009, based on revenue of $106m in the first six months of 2010. The goal is to reduce its financial dependence on Aeroflot into a position where it can order new aircraft itself. It currently operates six Russian aircraft and seven leased 737–500s and three 737–400s, but would like to phase out the Russian models; the current plan is for some 737s to be transferred to Donavia from the mainline’s outstanding orders by 2013.

Donavia is currently negotiating a strategic alliance with KMV, one of the regional airlines that Aeroflot is absorbing this year. Talks are ongoing between the two airlines and apparently a merger is under consideration.

The future

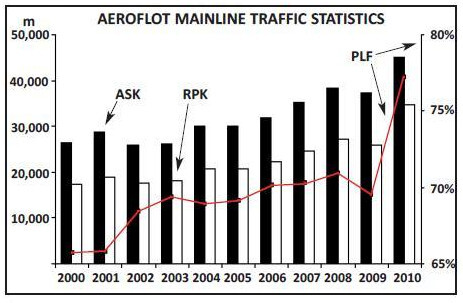

While the renewed emphasis on the domestic market and the new long–term strategic goals are positive signs for Aeroflot, at the same time it faces a series of challenges. Though in relative terms Aeroflot has fared well in the recession of the last couple of years, its continuing weakness has been yield, which has remained fragile in the face of fears that increasing fares would choke off the relatively robust demand that Aeroflot has held onto (mainline load factor leapt 7.7 percentage points in 2010 – see graph, above). Indeed passenger revenue per RPK fell from 8.6 US Cents at the mainline in the first nine months of 2009 to 8.4 US Cents in January–September 2010, while at the group level yield remained static year–on–year at 8.6 US Cents.

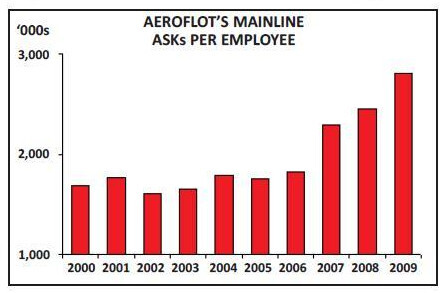

However, Fitch Ratings believes yield bottomed out in 2010 and forecasts that fares are set to rise through this year as business and consumer confidence returns to the Russian domestic and international markets. Fitch is also bullish about the capacity for further cost reductions at Aeroflot this year, which will be needed to offset the rising cost of fuel seen so far in 2011. Aeroflot has made substantial improvements in productivity over the last few years (see chart, below) but it needs to keep the pressure on in this area.

The debt levels also need to be managed carefully. As at the end of September 2010 the Aeroflot group had long–term debt of $2.2bn,a significant rise on the $1.9bn of long–term debt it had at the end of 2009, and mostly derived from the raising of $389m worth of three–year debenture bonds at an annual interest rate of 7.75%.

Aeroflot also faces operational issues; for example in December last year Aeroflot moved swiftly to sack Vladimir Smirnov, its deputy chief, following “errors which led to disruption” of Aeroflot’s flights out of its Moscow Sheremetyevo base following bad weather, when two–thirds of its flights were delayed in a few days after Christmas. Another problem is a lack of pilots, which has forced Aeroflot to open its own pilot training school this year, which the airline hopes will produce up to 200 new pilots a year (although the first will not graduate until 2012.

Then there are infrastructure problems.

Aeroflot would like Domodedovo airport to build a third runway, which potentially could persuade the airline to move operations there in 2020 from Sheremetyevo. The current Moscow base has a number of limitations, including in inability to base the eight 777s that Aeroflot has on order. Sheremetyevo also needs a third runway according to Aeroflot and in addition has poor rail and road infrastructure.

The latest airport directive from Prime Minister Putin is for a joint airport company encompassing Sheremetyevo and Vnukovo, the Moscow low–cost airport.

Aeroflot and the State The state still owns 51.2% in Aeroflot and the state–owned Bank of Russia another 12%, while in March this year VTB Capital, owned by the state–owned VTB Bank, bought a 5.9% stake in Aeroflot.

Interestingly, in the same month Aeroflot Finance (the finance arm of Aeroflot) increased its share in Aeroflot group from 7.2% to 10.4% in a share buyback deal that was essentially forced upon Aeroflot thanks to “a major shareholder selling a large block of shares and voicing an intention to go on selling”. That company was the National Reserve Corporation (NRC), which had built up a 30% stake in Aeroflot and is controlled by oligarch/entrepreneur Alexander Lebedev. He said that he would sell shares in Aeroflot in order to buy 44 Tu–44 aircraft for his airline Red Wings, which NRC bought in 2007. The charter carrier currently operates from Moscow Vnukovo airport to destinations in Europe and the Middle East with a fleet of nine ageing Russian models. NRC also owns 44% of Ilyushin, which is now part of the United Aircraft Corporation – and which produces the Tu–44 and all other Russian civilian aircraft.

Indeed from mid–December last year to the 3rd of January in 2011 the share price fell by 8%, after which Aeroflot decided to shore up the price by purchasing stock. However, Russian investment house Aton assesses this development as “neutral to negative for Aeroflot”, since “we believe the stock’s recent poor performance is a market reaction to rising fuel prices and a possible decline in traffic linked to political instability in Africa and the Middle East – in other words, the result of fundamental factors.

We think the buyback is not fully justifiable on economic grounds and believe Aeroflot should concentrate on operational activities rather than market interventions.”

That’s a logical argument and begs the question: just why is Aeroflot overly concerned about a relatively small drop in its share price, given the shares rose steadily from March until December 2010, finishing some 47% up through 2010?

The answer may be related to the pressures put on Aeroflot by the Russian state, not just though its direct shareholding but also increasingly via the public “guidance” given to it by senior government officials, and most particularly by prime minister Vladimir Putin.

For example, after being heavily criticised by Putin in early 2010 for a reluctance to “buy Russian”, in July Aeroflot announced a promise to buy more than 120 new Russianbuilt aircraft before 2020, whether Sukhoi Superjet 100s, Antonov An–140s, An 148s or MS–21s – with many of these destined for the six Russian airlines that the state is forcing Aeroflot to acquire later this year.

Aeroflot currently has an ageing fleet of 98 aircraft (almost all of which are leased) – its six Il–96s have an average age close to 20 years, while three MD–11Fs are 18 years’ old and 10 767s have an average of more than 13.5 years. Only the Airbus types have average ages of less than five years.

This spring Aeroflot was due to receive the first two Sukhoi Superjet 100s from an existing order for 30 of the type, which should enter service on domestic routes in the middle of May, initially on Moscow–Nizhny Novgorod (in central Russia) before being introduced on routes from the capital to St. Petersburg, Omsk and Kazan.

The Superjets can carry up to 98 passengers and have a maximum range of 4,400km, and were originally supposed to be delivered in 2008 until technical problems arose that reportedly related to a heavier weight than expected (compared with the design spec) and which led to increased fuel consumption and higher engine thrust requirements.

Aeroflot also has options for 15 more Superjets as well as a firm order for six Il–96- 300s, but the rest of its order book – some 125 aircraft – are for Western types, which is what angers Putin so much.

At Farnborough last year Aeroflot ordered 11 more A330–300s, which will start arriving this year and with delivery completion in 2013. The airline currently operates 10 A330–200s and -300s, which were originally a stop–gap before the delivery of 22 A350s. 22 787s are on order, for delivery from 2016 onwards, although Aeroflot is in talks with Boeing to receive two 787s as a “one–off” in 2014 in time for the Winter Olympics that will be held in Sochi in February of that year. Aeroflot is the official carrier for the event, and the delivery of two 787s would be seen as providing kudos for Aeroflot and, of course, for the Russian state.

In late 2010 Rostekhnologii confirmed an order for 50 737s, in -700, -800 and–900ER variants, all of which are slated for delivery to Aeroflot in the period between 2013 and 2017. The aircraft are worth £3.7bn at list prices and will be assigned to the six regional carriers that Aeroflot will acquire this year.

And before 2016 six 777–300ERs and two 777- 200ERs will be delivered, though this could potentially rise to 16.

This 777 order was agreed this March and Aeroflot claims it is paying just $1.2bn for the eight aircraft, which is almost half the official list price of $2.2bn. That essentially is the problem that Aeroflot faces – in today’s market Airbus and Boeing are offering aircraft that are very heavily discounted, but the Russian state wants Aeroflot to buy more Russian aircraft, even though commercially they would not be the sensible choice to an airline free of political interference.

Nevertheless, Rostekhnologii is also likely to order 50 MS–21s for Aeroflot. Built by United Aircraft, the MS21 is a single–aisle twin–jet that provides an alternative to Airbus and Boeing narrowbodies, and will be available for delivery from 2016 onwards.

Aeroflot is now qualifying its promise to buy large amounts of Russian aircraft by saying that all Russian aircraft need to be very keenly priced, with Saveliev insisting the government should abolish taxes and duties on imported components for Russian aircraft.

Aeroflot is also asking the government for help with reduced lease payments on the aircraft. It shouldn’t be forgotten that the state has been a huge help to Aeroflot in the last few decades, but in the ultra–competitive aviation market of the 21st century that influence may hinder more than it helps.

Given a free choice, would Aeroflot’s management voluntarily have agreed a deal to acquire six regional airlines (and in exchange for giving a reported 2.5% of Aeroflot’s share to state–owned Rostekhnologii) whose fleet is “severely outdated”, according to Saveliev? And without political prompting would Aeroflot have committed itself to a promise that will result in Russian aircraft accounting for half its fleet in a few years’ time?

| Fleet | Orders | Options | |

| AEROFLOT | |||

| A319 | 15 | ||

| A320 | 36 | 4 | |

| A321 | 18 | 8 | |

| A330 | 10 | 11 | |

| A350 | 22 | ||

| 737-700/800 | 40 | ||

| 737-900ER | 10 | ||

| 767-300ER | 10 | ||

| 777 | 8 | ||

| 787 | 22 | ||

| MD-11F | 3 | ||

| IL-96-300 | 6 | 6 | |

| SuperJet 100-95 | 30 | 15 | |

| Total | 98 | 161 | 15 |

| DONAVIA | |||

| 737-400 | 3 | ||

| 737-500 | 7 | ||

| IL-86 | 2 | ||

| Tu-154 | 4 | ||

| Total | 16 | 0 | 0 |

| GROUP TOTAL | 114 | 161 | 15 |