AMR: Capitalising on alliances, navigating labour challenges

April 2010

In the past six months American Airlines has transformed itself from a likely Chapter 11 candidate and a loser in the global alliance game to an airline that looks rather well positioned for the future. But will it successfully navigate its labour challenges?

Through 2008 and much of 2009, American’s parent AMR was seen by many as a Chapter 11 risk in a prolonged recession, given its labour cost disadvantage and pension exposure – both arising from the fact that AMR is the only one of the large US network carriers to have avoided bankruptcy.

AMR did well to secure $1.8bn of voluntary annual labour concessions in the spring of 2003 (literally on the courthouse steps), but four of its key competitors — UAL, US Airways, Delta and Northwest — achieved much greater savings as part of their Chapter 11 restructurings in 2002–2007.

Then all of American’s concessionary labour contracts became amendable in May 2008, just as fuel prices were soaring and the economy had begun to weaken. Many in the financial community considered Chapter 11 a likely eventual outcome, given that AMR could then also reap aircraft savings and eliminate unsecured debt.

To add to the woes, American risked being marginalised in key international markets because its global alliance–building efforts were going nowhere. Its decade–long efforts to secure transatlantic antitrust immunity (ATI) with BA seemed doomed because of BA’s dominance at London Heathrow.

Improved fortunes

And then came the blow that JAL was considering defecting to Delta and SkyTeam. AMR is fortunate in that it has what is probably the strongest US domestic network, a diversified global network and a powerful FFP, but in a world increasingly dominated by alliances it was destined to lose market share. However, through a combination of hard work and some luck, American has seen a reversal of its fortunes in recent months.

First of all, American took care of its liquidity needs when the US capital and banking markets opened in September 2009. The company raised $5bn in the second half of the year to bolster cash, refinance debt that was coming due in 2010 and fund aircraft deliveries.

This firmly extinguished any talk of bankruptcy. With $4.4bn of unrestricted cash at year–end (about 22% of revenues) and reduced near–term debt obligations, American will be able to weather the slowest and bumpiest of economic recoveries. As a bonus, the airline has fully funded its fleet plan for the next couple of years.

Then the global alliance issues were effectively resolved in February – something that materially enhanced American’s longer–term prospects.

First, JAL announced in early February that it would stay in oneworld. American and JAL immediately applied to the DOT for ATI.

Second, in mid–February the DOT tentatively approved oneworld’s application for broad ATI on the transatlantic, as well as a JV between American, BA and Iberia, with conditions that were acceptable to the airlines. Approval from the EU and a favourable final ruling from the DOT now seem virtually certain in the coming weeks.

As icing on the cake, American has also secured an interline/ticketing partnership with JetBlue in New York and Boston that could lead to bigger things – conceivably even oneworld membership for JetBlue eventually. The two announced on March 31st that, starting this quarter, they would collaborate in non–overlapping markets and were “exploring other commercial cooperation”. The deal includes a slot swap, with American getting 12 slot pairs at JFK and giving up slots mainly at Washington National.

This is a major coup for American, because JetBlue code–shares with and is partially owned by Lufthansa and previously seemed destined to end up in the Star alliance. Then again, JetBlue has made it very clear all along that it wants multiple commercial and code–share alliances at JFK.

Digging from a deep hole

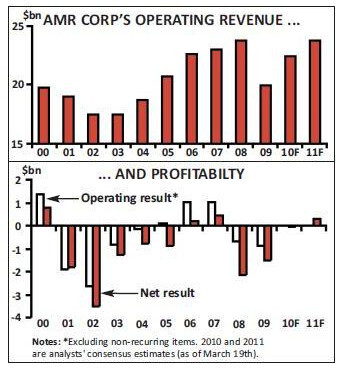

Late last year AMR unveiled a new business plan, “FlightPlan 2020”, as a strategic framework for the next 10 years. The five tenets of the new plan are to: “invest wisely, earn customer loyalty, strengthen and defend our global network, be a good place for good people, and fly profitably”. The key priority is to return to sustained profitability, but the past decade’s record is not very promising. After net losses totalling $8.1bn in 2001–2005, AMR had two modestly profitable years – 2006–2007, when it earned about $800m – before losing another $3.6bn in 2008–2009.

Last year’s performance was broadly in line with the other US legacy carriers’. AMR posted a $1.4bn net loss before special items on revenues of $19.9bn, up from the previous year’s $1.2bn loss. Mainline passenger revenues fell by $3.2bn or 17.5%, which was partially offset by significantly lower fuel prices.

Given all the uncertainty with the economy and oil prices, analysts’ forecasts for this year and 2011 are all over the place. But the current consensus estimates for AMR are a marginal loss of nine cents per share (about $34m) in 2010 and a modest profit of 81 cents per share ($315m) in 2011.

So, including this year’s anticipated loss, AMR has earned net profits in only two of the past 10 years. Its operating margins in those years were only in the 4.5% range, compared with the 6.5–7% margins seen in 1999–2000.

It is staggering to think that AMR could have such a dismal profit record when it succeeded in removing $6bn from its cost structure as part of the 2003–2007 Turnaround Plan ($1.8bn from labour and $4.2bn non–labour). Of course, those savings have been masked by the dramatic increase in fuel costs in recent years.

But American has taken many steps in the right direction, which raises hope for the future. To start with, it has been an industry leader in exercising capacity restraint. American pioneered the idea many years ago and the other legacy carriers followed. Everyone has benefited enormously, especially in the past two years. In 2009 American’s domestic mainline capacity was 14.3% below the 2007 level (similar to the sector’s decline).

AMR executives note that “this industry will not be profitable until we reach a supply/demand equilibrium that can sustain reasonable returns”. The airline expects its mainline capacity to be up by only 1% in 2010, made up of a 0.5% decline domestically and a 3% increase internationally. Virtually all of the growth will be due to the restatement of flights to Mexico that were pared back in 2009 due to H1N1 and the launch of Chicago–Beijing service that was deferred last year.

In recent quarters American has also excelled in revenue generation, outperforming all the other large network carriers in terms of RASM growth. This has been attributed to factors such as a more favourable entity mix, prudent revenue management, less discounting than competitors and the strength of the American network.

Like its peers, American has moved aggressively in recent years to unbundle its product and develop ancillary revenues. Its “other” revenues grew from $1.5bn in 2004 to $2.3bn last year.

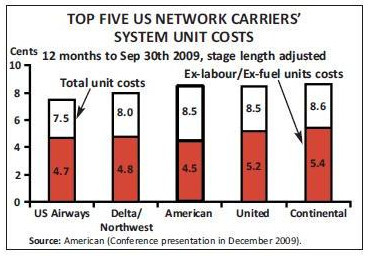

Costs remain under control. In the fourth quarter, American’s mainline ex–fuel CASM was up by 8.5%, driven by capacity headwinds, pension expenses, product investments and dependability initiatives. Thanks to a 16.5% year–on–year decline in fuel prices, total CASM was essentially flat.

American has a systematic hedging programme in place to dampen the effects of sharp price fluctuations on its cost structure. As of mid–March, the airline had about 30% of its 2010 fuel needs hedged with average floors at $67 and caps at $94.

American expects its total ex–fuel CASM to increase by 1% in 2010, due to revenue–related expenses, pension costs and higher aircraft lease expenses resulting from a recently sale/leaseback agreement. But the new aircraft will help the airline generate 2% more mainline ASMs per gallon of fuel this year.

The “cornerstone” strategy

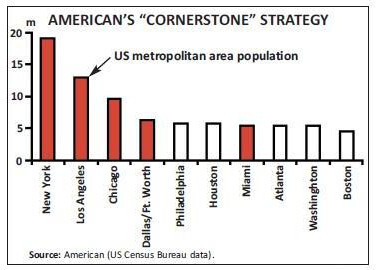

Thanks to the Turnaround Plan, American’s non–labour unit costs are actually very competitive with the other network carriers, resulting in unit costs that are in line with industry peers. American has five “cornerstones” or primary markets in the US that it believes make its domestic network the best in the industry — the four largest metro areas in the US (New York, Chicago, Los Angeles and Dallas/Ft. Worth) plus Miami, the hub of the Americas. These five metro areas are home to more than 50m people and each also supports unique industries and vibrant business communities. All of them except Los Angeles are AMR hubs. As CFO Tom Horton recently put it, “we are not as of today the biggest carrier in the world, but we are big where it matters”.

This spring, American and its wholly–owned regional unit Eagle are implementing a major domestic restructuring, which will further strengthen the five cornerstone markets and eliminate unprofitable or non–strategic flying at locations such as St. Louis and Raleigh/Durham.

There is nothing unique about this strategy. The past decade has seen the US network carriers increasingly retrench to their hubs and key markets as competition increased from LCCs, and the trend intensified in the past two years because of the need to cut capacity. The key markets are the ones most important to premium and corporate customers. Delta also recently announced plans to add service in Los Angeles and New York.

But American has a new reason to strengthen the cornerstone markets: they are all critical international gateways. They will offer important feed and global synergies for the planned JVs with BA/Iberia and JAL, as well as the other oneworld partners.

Bolstering global presence

As for regional service, there are two new developments this year. First, Eagle’s operations are being expanded with the addition of 22 new CRJ–700s from mid- 2010. Second, Eagle will offer a first class cabin on those aircraft and on its 25 existing CRJ–700s, which will be deployed in Chicago and Dallas. The aim is to offer customers a premium product with the same level of service as in mainline operations – another example of how AMR is now going all out to attract premium traffic. This spring’s key international moves will be the launch of Chicago–Beijing in April and three new international routes from JFK in April–May: Madrid, Manchester and San Jose (Costa Rica). American has reaffirmed its commitment to Chicago as its primary Asia gateway. Beijing will supplement the existing Chicago–Shanghai service, deepening AMR’s presence in what it calls a “critical market for the future”.

But much of American’s future effort will now focus on developing co–operation with oneworld partners and implementing the planned JVs — or “joint business agreements” (JBAs), as American calls them.

The transatlantic ATI/JBA regulatory approval process is on the homestretch. The comment period on the DOT’s tentative ruling ended in late March, and the DOT’s answers were then due within 15 days, so the final ruling could come any time. The EU is seeking comments on the airlines’ remedy proposals by April 10th. American said in its annual report filing that it expected to begin implementing the JBA in the second half of 2010.

The JBA is apparently broadly similar to the existing immunised transatlantic JVs. American, BA and Iberia are essentially combining their transatlantic businesses, which have a combined annual revenue of around $8.5bn. The airlines had a decade to plan it and analyse competitors’ JVs, so they have been able to pick the best strategies.

The airlines have not yet released estimates of the potential benefits, because it will somewhat depend on their ability to sit down and restructure schedules, decide on pricing strategies, etc. AMR executives call the figure “quite meaningful” and similar to the ranges given by other alliances.

The immunised JBAs are particularly important for corporate sales efforts, enabling the airlines to offer a one–stop shop for their corporate clients. AMR executives noted recently that “today global companies are increasingly looking to negotiate large parts of their airline network needs with one alliance”.

The new JAL/Japan opportunities are the result of several developments. First, the US and Japan reached a tentative open skies agreement in December 2009, which will for the first time allow immunised alliances; however, the US must grant ATI to alliances involving both JAL and ANA before the open skies pact can take effect.

Second, Japan plans to open up Tokyo’s Haneda Airport to more international flights when a fourth runway opens there in October 2010. JAL and ANA dominate the slots at Haneda, which is much closer to downtown Tokyo than Narita. Under the open skies treaty, US airlines will receive four of the 20 daily departures earmarked for non–Japanese carriers.

Third, JAL decided to stay with American and oneworld, rather than defect to Delta and SkyTeam. It was the lowest–risk solution; the airline did not want to deal with the upheaval of switching alliances while undergoing a complex bankruptcy restructuring, and it worried that an alliance with Delta might not secure ATI.

American and JAL quickly rushed in their application for ATI and a JBA, to match a comparable application already submitted by United, Continental and ANA. American and JAL, which currently have modest code–shares in place, hope that the JBA will enable them to improve efficiency and reduce costs, in addition to the usual revenue benefits arising from the co–ordination of fares, services and schedules made possible by ATI. The JBA will be “metal neutral” (meaning both airlines will benefit equally from a customer ticket purchase regardless of which one carries the passenger).

The DOT is expected to look at the two ATI applications in concert. Approval seems highly likely, given that the proposals would ensure roughly equal US–Japan market shares for the three global alliances. The airlines expect the authorisations by the latter part of this year, so implementation could be in the first–half of 2011.

In mid–February American and four other US airlines applied to the DOT to serve Haneda. American is seeking to operate from JFK and Los Angeles (the largest markets between the US mainland and Tokyo), to complement its existing Narita flights from Chicago, JFK, Dallas and Los Angeles. Delta is proposing service from Detroit, Los Angeles, Seattle and Honolulu; United from San Francisco; Continental from Newark and Guam; and Hawaiian from Honolulu.

A key benefit for American, United and Continental would be the ability to connect to JAL’s and ANA’s extensive operations at Haneda. Delta applied for all four slots available to US carriers because SkyTeam is the only alliance without presence at Haneda.

To everyone’s relief, the Japanese government declined the $1.4bn capital investment in JAL that American, oneworld and TPG had lined up. But American indicated in a subsequent SEC filing that it had agreed to negotiate in good faith to provide such an investment in the future if invited to do so (its contribution would not exceed $300m). Also, American gave JAL a guarantee for the first three years that JAL would realise at least $100m in annual incremental revenue from the ATI and JBA. It is obviously in American’s and oneworld’s interest to see a strong and vibrant JAL (and not see it continue to shrink).

American is poised to gain market share on the Pacific through both closer co–operation with JAL and the open skies pact, which replaces a 1952 treaty under which Delta/Northwest and United enjoy special rights. In particular, American should narrow the gap with Delta, which has a 20%-plus share of the North America–Japan market (about three times American’s), a large Narita presence and extensive beyond–rights. However, because of airport and slot constraints in Tokyo, the market share shifts can only be very gradual.

While American is making JAL its exclusive partner in northeast Asia, elsewhere in the region it will rely on Cathay, Qantas and other oneworld members. It is also actively trying to recruit new members, such as its code–share partner China Eastern (which is expected to announce its alliance choice in the near future). Kingfisher, India’s leading domestic airline, is set to join oneworld probably in 2011.

Fleet renewal plans

Even though the recent headlines have centred on Asia and Europe, American remains focused on consolidating its leadership in Latin America, its largest international region that last year accounted for 21% of its total revenues (compared with Atlantic’s 15%, Pacific’s 4.3% and Domestic’s 60% share). Oneworld is fortunate to have LAN and to have attracted Mexicana, which joined late last year. Efforts now focus on Brazil and courting Gol. American and Gol recently agreed to add a code–share deal to their FFP co–operation, starting this quarter subject to government approvals. American is well into the process of replacing its fleet of MD–80s with 737- 800s. Having taken delivery of the first 31 of those aircraft in 2009, the airline is receiving another 45 in 2010 and at this point is committed to taking eight in 2011. All of those aircraft are fully financed thanks to a $1.6bn sale–leaseback deal with GECAS in late 2009.

Beyond–2011 there is much flexibility. Current firm commitments include only 11 737–800s (in addition to seven 777s) in 2013–2016. The MD–80 replacement process will take a while because of the sheer size of the fleet, which will still exceed 200 in number at the end of 2010. The retirement schedule can be adjusted to suit market conditions. Or if Boeing comes up with an attractive new narrowbody type, American would have the ability to move forward with that.

As for the widebody replacement plans, American has a deal with Boeing that enables it to retain delivery positions on 100 787–9 Dreamliners (42 orders and 58 purchase rights) without any obligation until May 2013, while it tries to reach a deal with its pilots. But each of the aircraft needs to be reconfirmed at least 18 months prior to the scheduled delivery date. The original delivery schedule (2012–2018) has not yet been revised to take into account Boeing’s production delays, but the reconfirmation terms are expected to remain consistent with the original agreement.

The labour challenge

AMR continues to take a measured approach to all capital spending. On the non–fleet side, the emphasis is on investments that will help keep the company competitive in the long term. That includes investments in items that customers really value (such as lie–flat seats), airport lounges and other facilities, operational dependability and new technology. While labour tensions are resurfacing at many US airlines, the situation at American is currently the most contentious. It has had three major work groups in federally mediated contract talks for quite some time and two of those – flight attendants and TWU–represented mechanics and ground workers – have asked to be released from mediation. If the NMB grants those requests, the unions would be moving closer to a strike vote. The pilots are still at the negotiating table, but AMR executives note that “it is fair to say we are far apart”.

There is much hope that strikes will be avoided, in part because the TWU and management have had a collaborative relationship in the past. Also, federal law in the US makes it quite difficult for airline workers to strike; if all else fails, the President or Congress may intervene. But it is also hard to see how the issues could be resolved, because the unions are determined to roll back the 2003 concessions.

American’s objective, as it has made clear to all its unions, is to ensure that its costs are competitive. The challenge, as CEO Arpey put it, is to “have a constructive dialogue that on the one hand recognises the competitive disadvantage created by the bankruptcy of all these companies [United, US Airways, Delta and Northwest], but on the other hand does not suggest that we are pushing across the table to organised labour those bankrupt contracts and saying that is what we need for our company to be successful”.

As Arpey explained it, American does not need the bankrupt competitors’ contracts because it has been doing a good job on the revenue side in terms of driving RASM premiums. It believes it has a superior network, franchise and global partnership that “can beat those other guys”.

Furthermore, over time there will be convergence as American’s competitors will not be able to sustain their bankrupt labour rates and benefits. In fact, American may not have to wait that long since many of the other legacies will be trying to reach new contracts with key unions over the next year or so.