Southwest: Low-cost pioneer tackles new challenges

April 2009

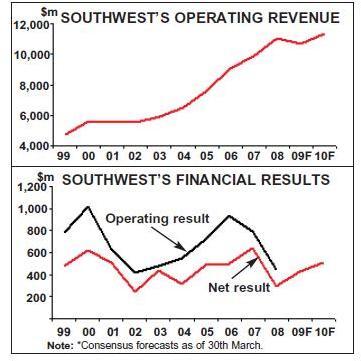

In past recessions Southwest Airlines, the low–cost pioneer and the largest US carrier in terms of domestic passengers, could always be counted on to grow and capture market share, financially outperform its competitors and provide a safe haven for investors. But this time around Southwest is losing money, has suspended its fleet growth and is cutting capacity by 5% in 2009. Are the struggles only temporary? Has Southwest lost some of its key competitive advantages?

Southwest has reported net losses for three consecutive quarters. The losses in the second half of 2008 were entirely due to large mark–to–market unrealised losses on fuel hedge contracts and therefore not that surprising. But the result for the first quarter of 2009 was negative even when special items were excluded – Southwest’s first exitem quarterly loss since 1Q 1991. The exitem net loss was small – only $20m or 0.8% of revenues – and the operating margin was still positive (1.3%), but the other two large US LCCs, JetBlue and AirTran, both achieved 9% operating margins in the latest period.

Southwest faces challenges on several fronts. First, it has lost its fuel hedge advantage. After reaping savings from fuel hedges to the tune of $4.5bn in 2000–2008, the airline saw its hedges turn into a huge liability when the price of oil collapsed late last year. Having neutralised the hedge positions, Southwest has now begun to hedge again, but it is starting from the same position as the rest of the industry.

Second, Southwest faces challenges related to its decision to suspend growth. This year will see the airline’s first–even annual contraction. How much will unit costs rise as a result? Can employee morale be maintained during a period of contraction? Would Southwest have to forgo good market opportunities that might arise from a pullback by competitors?

Third, Southwest faces significant cost pressures even without the reduction in ASMs, particularly in the airport, maintenance and labour cost categories. New labour contracts negotiated in recent months all grant pay increases, ensuring that Southwest’s workers remain among the best–paid in the industry.

Not surprisingly, Southwest has announced new measures aimed at offsetting the cost increases, including a new voluntary early–retirement programme. But will the workers be interested in light of the lack of alternative employment opportunities in the current economic environment?

Southwest’s share price has fallen sharply in recent months. Its market capitalisation has roughly halved since July 2008. Many analysts have a “sell” recommendation on the stock, arguing that the “premium multiple” previously enjoyed by Southwest is no longer justified in light of the “no growth, little hedging” strategy.

Several analysts have suggested that Southwest is now “just like anyone else” from the earnings power point of view. A mid–April research note from Bank of America/Merrill Lynch made the point that Southwest’s net margin gap vis–à-vis the industry has narrowed to the point that the gap could all but disappear in 2009 and 2010. Historically, Southwest’s net margin has typically led the industry by 5–6 percentage points, but during recessions the lead has been at least 10 points. If the margins were to converge, in ML’s view Southwest would face a “much more challenging competitive backdrop than it has ever experienced”.

However, it is also possible that Southwest is responding appropriately to the economic crisis and will emerge from it as strong as before. Brokerages such as Raymond James remain very bullish on the carrier, arguing that it provides “lower–risk exposure to an early cyclical recovery in airlines”, given its higher leisure revenue mix,substantially lower leverage and likely continued access to capital.

Southwest’s CEO Gary Kelly argued very effectively at a recent conference why his airline still stands out from the crowd. First, all of Southwest’s traditional strengths remain intact. The airline remains a low–cost producer, with an unbeatable culture, staff morale and brand. It has one of the industry’s strongest balance sheets and $8bn worth of unencumbered assets. As the only US airline with an investment–grade credit rating, Southwest is better placed than any other airline to access the credit markets, should it become necessary.

Second, despite this year’s ASM decline, Southwest will still be able to add three major cities to its network, thanks to new flight schedule optimisation tools. According to Kelly, the airline is also prepared to “take advantage of opportunities if some of our competitors falter”.

Third, Southwest has developed new strengths and capabilities as it has adapted its business model to a changing competitive environment. There are new products aimed at bringing in extra revenues and further strengthening the brand. Also, the past few years’ technology development drive is finally bearing fruit, giving Southwest new capabilities to manage revenues, optimise its network and code–share internationally.

The fuel hedge issue

Southwest has continued to outperform the industry on the revenue front, reflecting its higher concentration of leisure traffic and lack of international exposure. Its passenger unit revenues fell by only 2.8% in the first quarter, compared to a roughly 10% average domestic industry decline. As recession bites, more travellers (both leisure and business) are likely to switch to LCCs. That and the legacy carriers’ much greater capacity cuts should mean that LCCs will continue to gain market share. Overall, Southwest gained enormously from its post–2001 fuel hedging strategy. In the wake of September 11, Southwest was the only US airline with the cash (and the foresight) to take on extensive new hedges at crude oil prices in the $20s and $30s (per barrel). Those hedges paid off handsomely when oil prices subsequently surged, saving the airline $3.2bn in 2000–2007 and enabling it to continue reporting healthy 8–10% operating margins even in the toughest years. By 2007 the hedges were wearing off, but when oil prices surged to new heights last year, Southwest still had the best hedge position in the industry (by a wide margin) and reaped another $1.3bn in savings in 2008.

The collapse in oil prices in the second half of 2008 meant large mark–to–market unrealised losses on hedge contracts and the first quarterly net losses in 17 years. However, thanks to $1.3bn of savings from fuel hedges in the first half of 2008, Southwest achieved its 36th consecutive year of profitability. The $178m net profit and 5.8% operating margin in 2008 were excellent results in an extremely difficult year.

Southwest acted quickly to reduce its hedge exposure. After having 75% of its 2009 fuel needs hedged at an average crude equivalent price of $73, plus further significant hedges in 2010–2012, in November- December the airline reduced its net hedge position to only 10% of fuel needs each year between 2009 and 2013. It was done by selling swaps against the existing out–of–money fuel hedge positions, effectively capping the mark–to–market losses at around $1bn. Southwest paid no additional premiums, avoided having to fork out an additional $500m in cash collateral and will realise the $1bn in losses as future fuel is consumed.

The cash collateral requirements on the fuel hedges had caused Southwest’s unrestricted cash holdings to dip as low as $1.3bn (11.8% of last year’s revenues) late last year – quite a deterioration from the $5.8bn held six months earlier (which included cash deposits received from hedge counterparties). By revising deals with hedge counterparties and raising more than $1bn in cash through credit lines, a public debt offering and aircraft sale–leasebacks, Southwest raised its unrestricted cash position to $1.8bn at year–end.

Further sale–leasebacks on 737–700s helped raise unrestricted cash to $2.1bn by March 31. Southwest also has $200m available under its unsecured revolving credit line. In April another $105m was raised through sale–leasebacks, with a similar amount expected from a second tranche later this quarter. It all adds up to a perfectly healthy liquidity position.

The management has obviously had to work extremely hard to stabilise the situation arising from the out–of–money fuel hedges, but they could not have managed it any better. It is also worth bearing in mind that Southwest never had a fuel hedge advantage before 1999, and it had a significant advantage only in 2008.

The “no-growth” strategy

With the slight increase in oil prices in recent months, Southwest has started to rebuild its hedge position using call options, which provide upside protection while allowing the airline to benefit from lower fuel prices. As of April 16, Southwest had 50% of its 2Q needs capped at $66, 40% of second half 2009 needs at $71 and 30% of 2010 needs at $77. After long growing at a brisk 8–10% annual rate, Southwest began to slow down in 2007 and last year grew its ASMs by only 3.6%. In October the airline deferred some of its 2009 deliveries, and in January it further revised its aircraft delivery schedule and indicated that its ASMs would decline by 4% in 2009. In mid–April the ASM decline was revised to 5%.

Southwest is still taking 13 new 737- 700s in 2009, but because it is retiring or returning to lessors 15 older 737s, the size of the fleet will decrease by two aircraft to 535. Under the revised deal with Boeing, Southwest deferred 737–700 deliveries from 2010–2012 to 2013–2016. It now has only 10 firm deliveries in 2010 and 10 in 2011. These and the earlier deferrals reduced capital spending from its peak in 2009–2010 by $1.4bn.

Of course, the fleet growth suspension is only temporary. According to local newspaper reports in Dallas, Southwest has made a commitment to its pilots to begin growing the fleet again in 2011. The new tentative pilot contract reportedly stipulates that the airline must have 541 aircraft by year–end 2011 and 568 by year–end 2012. There is obviously flexibility to accelerate growth at any point. Total firm orders, options and purchase rights through 2018 remain at 220.

Southwest is finding it easier to temporarily suspend fleet growth because it has new schedule optimisation technology at its disposal which it did not have before 2004. The new tools have allowed it to trim less popular flights and reallocate the capacity to promising new markets.

The ASM reduction will come from reduced aircraft utilisation. The schedule optimisation effort often involves eliminating early–morning or late–evening flights, which would not be any more popular elsewhere in the network.

Cost pressures

It is hard to imagine that employee morale would be seriously dented by the temporary shrinkage. But is interesting how the retrenchment and gloomy industry prospects have helped bring to conclusion difficult contract talks. Since January four of Southwest’s key unions – mechanics, ground workers, flight attendants and pilots — have reached agreement or ratified new 3- 5 year contracts. Some of those deals incorporate job security protections, including no furlough clauses and limits to maintenance outsourcing and domestic code–sharing. There is a perception that Southwest’s cost advantage over competitors has narrowed, especially because of the legacy carriers’ deep cost cuts earlier this decade. Also, AirTran now has slightly lower ex–fuel CASM than Southwest on a stage length adjusted basis. But Kelly estimated in early March that Southwest retains a cost advantage over the legacy carriers “ranging from 50% to near–100%” on a stage length adjusted basis – that is now, without the fuel hedges.

Southwest has remained among the low cost leaders despite being 38 years old with a senior workforce and industry–leading wages. It has the highest–paid pilots for narrowbody aircraft in the US industry. The airline has held its non–fuel CASM at around 6.5 cents for the past eight years, thanks to continued productivity improvements.

But keeping costs under control will be a major challenge as the ASM base shrinks. The pressures were already evident in last year’s fourth quarter, when ex–fuel CASM rose by 6.9%, reflecting increased airport and maintenance costs and ASM growth grinding to a halt. In the first quarter, ex–fuel CASM rose by 8.4% as capacity contracted by 4.1%. By most estimates, Southwest will see its ex–fuel CASM surge by 8–10% this year.

The maintenance cost pressures, evident since mid–2008, reflect a sharp increase in the number of engines coming up for major overhaul. On the airport front, as a domestic carrier, Southwest is heavily exposed to the cost increases resulting from sharp declines in airline service at US airports.

The new labour deals also guarantee continued cost pressures. The tentative five–year pilot contract, which was endorsed by the union’s board in late March, includes 2% annual pay increases for the first three years (two of which are retroactive), further pay rises in 2010 and 2011 depending on profitability and improved retirement benefits. The new tentative four–year flight attendant contract provides pay increases and improvements in retirement and other benefits. The mechanics’ new four–year contract grants 3% pay increases in most years, plus 7% in possible bonuses, while the ground workers’ three–year deal also provides 3% annual pay increases.

As in the past, the aim is to try to offset pay increases with productivity improvements. The contracts incorporate work rule changes, flexibility provisions and some were even described as “cost neutral”. But, with ASMs declining, it will be an uphill battle to maintain productivity. A recent report from JP Morgan noted that Southwest’s efficiency, as measured by daily departures per aircraft and employees per aircraft departure, already deteriorated sharply in the first quarter.

On the positive side, Southwest got the contract negotiating process out of the way (for all unionised employees except for customer service and reservations agents) and the workers seem happy with the new contracts. The latter is particularly important for a company that regards its culture as its greatest strength.

But Southwest will need to find some cost savings. To that effect, the airline announced in mid–April that it hopes to trim staff numbers through a new voluntary early retirement programme covering nearly all of its workers (decisions required by June). There is also a salary freeze in place for senior management, and CEO Kelly has voluntarily cut his 2009 base salary by 10%.

New revenue strategies

Although the two previous voluntary early–out programmes since 2004 were successful, such a programme may be less popular in the current economic environment. Southwest has never had a furlough or pay or benefit cut and would use those strategies only as a last resource, but some analysts now question how long the no–furlough strategy can last. Since mid–2007 Southwest’s primary focus has been on boosting revenues. Originally the purpose was to compensate for the waning of the advantageous fuel hedges. The airline also realised that, as the largest domestic carrier, it was uniquely well positioned to develop ancillary revenues and capitalise on southwest.com. It wanted to improve its customer experience and go past the “one size fits all” approach it had used in the past, in particular to appeal even more to the business customer.

The result has been a batch of revenue initiatives, including a new “Business Select” product and a new boarding method, both introduced in late 2007. Business Select is a modest premium product even by LCC standards, and Southwest never adopted assigned seating. However, Southwest did not need to go further than that, because it already carried large volumes of business customers and had a business model that its customers loved. After one full year, customer response to the new offerings has been “overwhelmingly favourable”, and Business Select brought in $75m extra revenues last year. It will take Southwest another year or two to complete all of its planned revenue initiatives, many of which are technology- enabled and include a new FFP and a new southwest.com.

Growth opportunities

While developing new products aimed particularly at business travellers, Southwest maintains a commitment to low–fare leadership and what it calls a “no hidden fees” policy (meaning no fees on items that previously were included in the ticket price, such as checked bags). Some analysts have questioned the wisdom of the no–fees policy, arguing that, now that every other US airline charges extra for items such as checked bags, Southwest is just leaving large amounts of money on the table. But Southwest’s management feels that “no hidden fees” is a key element of the low–fare leadership, helping to reinforce the brand and maybe even being a positive contributor on the revenue side. In recent years Southwest has become more strategic with its growth efforts. It has pulled back in less profitable markets, focused expansion on selected key cities and grown aggressive at those locations. After long flying mainly to cheaper and less congested secondary airports, the airline is now adding service at big legacy hubs or highly competitive major airports. There is no desire to depart from the point–to–point strategy, though at many of its focus cities Southwest has effective hub operations. At present Southwest is determined to continue flying just one aircraft type, to retain simplicity and low costs.

Southwest’s initial experiments with the “major hub” strategy, at Philadelphia (US Airways’ hub) since 2004 and at Denver (United’s hub) since 2006, have been huge successes. Denver has been Southwest’s fastest–growing city; after only three years, the operation has grown to 115 daily departures to 32 destinations. After several “route alignments” since August 2007, which have eliminated some 10% of daily flights from its schedule, Southwest is stepping up the new expansion strategy this year with three important city additions: Minneapolis, New York LaGuardia and Boston Logan.

Minneapolis is a classic overpriced and under–served market, but it represents a bold move for Southwest since it is the home base for Northwest (now part of Delta). Southwest started cautiously with service only to Chicago Midway, where it has a hub operation, but demand has exceeded expectations and a second route, to the Denver stronghold, will be added in May. With fares initially as low as $49, there is potential for the famous “Southwest effect”.

LaGuardia, which will be added on June 28, is a very big move for Southwest, which has so far served the New York area only via Islip on Long Island. Southwest is gaining access to this congested hub by acquiring ATA’s 14 daily slots at LGA for $7.5m (as part of its former partner’s liquidation process). Southwest will connect LGA to two of its key markets, Chicago Midway and Baltimore–Washington, with a total of eight daily flights (the ATA slots plus one return flight outside the slot control hours). The LGA operation will be too modest to have real competitive impact, and slot restrictions will prevent rapid expansion. But Southwest’s customers have wanted LGA service for a long time. It will be an interesting experiment for the airline.

Southwest is looking to add Boston Logan to its network this autumn. The airline already serves the Boston region through Manchester (New Hampshire) in the north and Providence (Rhode Island) in the south, but it is not drawing many customers from downtown Boston, so Logan represents an opportunity to draw new traffic. Since there are no slot or space constraints, Southwest sees tremendous growth possibilities.

Southwest has shifted its focus from secondary to major airports for a number of reasons. First, it is now more able to deal with congestion and delays at large East Coast hubs after gaining experience with ATA and now that it has more sophisticated scheduling tools to help minimise the impact of any delays at LGA.

Second, Southwest is responding to changes in the competitive environment. In the old days it could go to a region like Boston, pick an alternative airport and people were happy to drive long distances to get cheap fares. That was when Southwest was the only low–fare airline. Now that there is low–fare competition throughout the US, including JetBlue with a major presence at Logan, the strategy no longer works.

Third, Southwest’s large size and nationwide presence probably obligates it to serve the nation’s largest city, New York, as well as the main gateway airports to cities such as Boston. Fourth, focusing on the main airports obviously helps cater better for the business segment.

While Southwest clearly still has good opportunities to develop its network in the US, it has taken the first concrete steps to go international: signing code–share deals with Canada’s WestJet and Mexico’s Volaris, and seeking US–Canada route authority from the DoT (even though it does not currently have plans to operate to Canada with its own aircraft). The Canada and Mexico code–shares, to be flown by partners’ aircraft, are expected to start in late 2009 and early 2010, respectively, when Southwest will have the systems in place to sell international itineraries. The next stage could be similar deals to Europe and Asia, though that may be a couple of years away.

At some point in the next few years, Southwest is expected to begin its own flying to “near international” destinations. There is considerable pressure from the pilots, who have questioned why Southwest is not launching its own service to Mexico, Canada or the Caribbean, like JetBlue, AirTran, Frontier, WestJet and other LCCs are. The new pilot deal limits near international code–sharing to 6% of the flying done by Southwest’s pilots.

| Firm orders | Options | Purchase rights | Total | |

| 2009 | 13 | 13** | ||

| 2010 | 10 | 10 | ||

| 2011 | 10 | 10 | 20 | |

| 2012 | 13 | 10 | 23 | |

| 2013 | 19 | 4 | 23 | |

| 2014 | 13 | 7 | 20 | |

| 2015 | 14 | 3 | 17 | |

| 2016 | 12 | 11 | 23 | |

| 2017 | 17 | 17 | ||

| Through | ||||

| 2018 | 54 | 54 | ||

| TOTAL 104 | 62 | 54 | 220 | |