Another go at German consolidation

April 2009

It is an often–quoted mantra that the airline industry will and should consolidate — and a widely held belief that this would be a good idea. There is also a tendency to regard European aviation as a homogeneous market — ignoring the significant national and cultural differences between the individual states (and sometimes even within those countries). The recent strategic moves by the German carriers should really be viewed in context of their own country’s historical background and physical geography, but these moves in the short–run should at least pave the way for some reasonable consolidation in the German market place — and may even generate some reasonable returns in the domestic scene through this downturn.

A little over a year ago, Air Berlin tried to push the German domestic industry into the latter stages of consolidation. Having already acquired two weak competitors (dba and LTU), it had arranged a tie–up with Arcandor (aka Thomas Cook) to acquire Condor in return for a shareholding stake from the conglomerate. This in itself spurred Lufthansa to start negotiations with TUI (the other major charter player in the German market, and one trying ineffectively to operate low cost scheduled services) with the idea of merging the TUIFly scheduled operations with Eurowings and germanwings. Air Berlin’s Condor deal was indigestible – partly because of regulatory issues and partly because of the crash in Air Belin’s share price – and the Lufthansa/TUI tie up likewise fell apart, probably because of what was seen as an unsustainable model at TUIfly.

In late March, meanwhile, Air Berlin announced a second attempt to consolidate the industry further with a strategic tie up with TUI Travel. The travel group will take a near 20% stake in Air Berlin for €65m (helpfully boosting the equity position on the balance sheet) while Air Berlin from October will acquire a 20% stake (for €36m cash) in HLF, the parent company of TUIfly.com and Hapag Lloyd Express (HLX). As a result Air Berlin will take over the scheduled European route network of the disruptive competitor (with 17 aircraft wet–leased from HLF) while TUI Travel will finally be able to exit a segment of the market that really does not fit its (new UK–managed) business model.

The deal is being structured to ensure that there are neither objections from the German Cartel Office (nor Brussels) nor create difficulties from among the group’s pilots. The Air Berlin management stated that it had persuaded TUI to take the brunt of restructuring the loss–making scheduled route network (TUI separately stated that TUIfly scheduled operations provided an operating loss of €35m in the year to October 2008) — which carried 5.3m passengers last year — and that when it takes over the slimmed–down operations the remaining routes will all be breaking–even at worst. There will be an element of overlap, but the prime benefit for Air Berlin (and Lufthansa for the matter) will be the removal of a struggling competitor that had had a severe impact on yields.

Lufthansa, meanwhile, after making the successful acquisition of SWISS, in the past year announced plans for the gradual acquisition of SN Brussels (with an initial 45% stake and an option to build to a majority) and found that Michael Bishop finally exercised the put option to them of his controlling 50%-plus stake in British Midland. Lufthansa also started using its wholly–owned subsidiary Air Dolomiti to start a base of operations at Malpensa (in the wake of the withdrawal by Alitalia from the Milan hub and the “new improved” Italian flag carrier’s retrenchment to Rome) and found that its suggestion to take over the Austrian government’s stake in Austrian Airlines for less than nothing was to be accepted.

Both these carriers' acquisition streams could be said to stem from the same underlying fundamentals. Germany is a federation of states with a plethora of important commercial and business links between respective main cities. Despite the density of population in the North Rhein/Westphalia region and the industrial concentration in the Ruhrgebiet, there is no prime conurbation that generates a strong underlying level of O&D demand. The commercial links have led to a preponderance of commercial arrangements for domestic and international air travel – ones that Air Berlin through its acquisition of dba and LTU has tried to wrest from Lufthansa; while the lack of very strong O&D demand for Lufthansa at its main hub in Frankfurt (in contrast to that enjoyed by BA in London or Air France in Paris), combined with the capacity constraints there, has led it to try to develop a wider multi–hub approach.

All of these planned acquisitions are naturally subject to approval by the competition authorities. The proposed Air Berlin deal, despite an element of overlap, is unlikely to create the regulatory opposition it encountered on the Condor deal. Although there is a conspiracy theory that suggests that Brussels really wants to encourage consolidation of the European legacy carriers into two (AF/LH) or three groups (+ BA), Aviation Strategy understands that the initial discussions suggest an unacceptable imposition of conditions (particularly in Brussels), and there are some increasing doubts on the Viennese deal — but Lufthansa is quite capable of walking away from either to let one flail and the other fail.

However, the acquisition of the bmi stake has been delayed – it was meant to take place by the end of January – while at the Lufthansa results meeting management seemed to suggest that there may be another protocol in the original agreement that is still under discussion.

Lufthansa

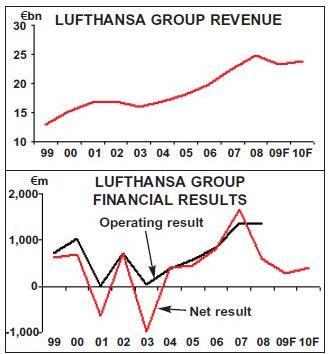

Meanwhile in the past month both the German quoted carriers have released results for the last year, along with the usual attempts to explain their respective performances. Lufthansa’s performance in 2008 appears to have been a game of three halves. The year started off fairly well, despite substantial increases in fuel costs, and the group appeared well hedged against increases in the price of oil, helped by the strength of the Euro. But traffic growth started weakening from midyear as fuel prices peaked and the world economy came to a halt in September.

One saving grace for the German flag carrier was that this was the first full year consolidation of SWISS (prior to July 2007 the rump of Swissair had been treated as an associate item) and it could finally publish operating profits little changed from the prior year period – which in turn had been its best ever. Another ironic benefit (just) was that one of its counterparties to its hedging transactions failed so dramatically in September that it removed a substantial number of (even by then) out–of the- money contracts.

Total group revenues in the year grew by 11% to €24.9bn, costs by 13% and underlying operating profits fell by only 2% to €1,354m. Net profits – in the absence of the capital gain in the previous year from the sale of its stake in Thomas Cook – dropped by 64% to €599m, and the group has proposed a dividend of €0.70. Lufthansa has the most highly developed conglomerate structures of any of the majors in Europe (fashion is not necessarily one of its attributes) but for it, the holding company structure appears to work well.

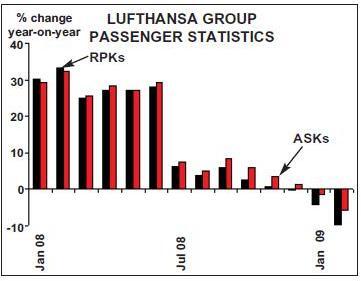

The passenger business naturally is by far the largest component – accounting for more than 70% of revenues and 53% of operating profit in 2008. Total RPK grew by 15.6% while capacity increased by 14.2% for the year. This includes the full year consolidation of SWISS, which accounts for 22% of the total output. Lufthansa’s underlying traffic grew by a more modest 3.5%, slightly behind a 5% increase in capacity, while the Swiss national carrier increased both demand and capacity by 12%. The company reacted quite quickly to the changing environment through the year and started reducing capacity growth as demand started to evaporate. At least until the full financial crisis hit in September, the underlying rate of growth in premium traffic maintained a reasonably positive impact on yields – helped by the fuel surcharges, particularly on long–haul operations.

With a modest increase in the stage length, underlying unit revenues appear to have grown by 1.5% — although the strength in the Euro reduced this in published terms to a 1.3% decline. Lufthansa retains a certain traditional impenetrability when presenting its numbers and delving into the passenger division costs is no mean task. Overall costs were up by 17.8% and published unit costs by 2.2%. Underlying unit costs excluding currency movements probably grew by nearer 5% year on year – suggesting that unit costs excluding fuel and currency may have fallen by up to 5%. This suggests there really is an element of cost control and flexibility in the business model (something the management has been saying that it has put in place since the 2001 downturn) that had not been there in previous cycles.

The passenger division operating result fell by a modest 12% to €722m. SWISS provided some €314m of this (against €127m for half of 2007) without which Lufthansa would have reported at least a 40% decline in the division’s profitability. The cargo division ironically had a good year – despite the significant slowdown from the middle of the year and the disastrous traffic performance since September. Traffic was down by 2% for the year while capacity (which of course includes belly–hold capacity) grew by 2.8%. Yields benefited from the mechanistic fuel surcharges for most of the year and underlying cargo unit revenues excluding currency probably rose by 5% year on year. Total divisional revenues were up by 6% to €2.9bn while operating results jumped by 20% to € 164m. The maintenance operation of Lufthansa Technik – the world’s largest MRO business (see the table in last month’s issue of Aviation Strategy) – despite Euro strength also saw revenues grow by 4% and profits up by 2% to €299m. In the other operating divisions, Catering – again hit by the dollar movement in the year but also by the increase in food prices – saw profits fall by 30% to €70m (but at least it is profitable) while IT services (which only accounts for 3% of the total) brought in profits of €40m.

Fuel of course was the killer in the year. Total group fuel costs jumped by 40% to €5.5bn – and could have been some €1bn higher without the benefit of the hedge portfolio and the Euro strength. In the fourth quarter the hedges went into reverse, and the fuel bill was some €20m higher than it would have been had the company not hedged – what appears to be technically known as an “inefficient” hedge. These will continue – it appears that the current average hedging price sits around the $90/bbl equivalent – and that at $50/bbl the company’s net fuel purchase price will be some 10% over market spot rates. Lufthansa is not alone in this, but probably retains some benefit from Lehman’s collapse. Management has presented its expectations for the 2009 full year fuel bill – at the then current forward rates they expect fuel costs to fall by 60% to €3.2bn (even below the 2006 level) with a reduced exposure to the volatile commodity – a 10% movement in the price having a 5% impact on total fuel costs.

Management was fairly adamant that the group would remain “significantly” profitable in the current year – although at the moment there is naturally very little visibility. In the cargo division LH will be parking a handful of its full–cargo MD11Fs and looking to cut capacity by 20% for the year, while by putting employees on short time working (one of the real advantages of the union negotiations of the past few years) it aims to cut employee costs by some 30% and overheads by some 20%. In the passenger division it has been manipulating capacity down in terms of frequency, although stating that it will be re–configuring some of the long–haul aircraft to reduce the J–class capacity and increase Y–class seating so that underlying seat–kilometre capacity would only be falling by around 1–2%.

This, however, is being negated by the growth in capacity presented by the opening of a base at Milan’s Malpensa (using Air Dolomiti) – taking advantage of Alitalia’s retrenchment to Rome, and to fight easyJet’s establishment as the largest north Italian carrier – and at the results meeting management seemed to suggest that overall capacity would only be flat to slightly down. The airline may adjust this further. The company boasts of its diverse holding company structure, but in all honesty the profitability is primarily driven by the passenger operations, and these will no doubt be suffering a severe downturn this year; the only question being by how much.

Air Berlin

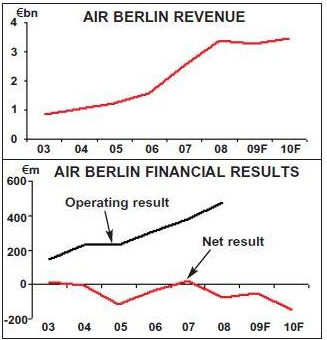

Meanwhile, the balance sheet is in good health – even though in the current environment along with everyone else at the moment they are probably haemorrhaging cash. Capital expenditure in 2008 was fully funded from cash flow. In the current year the group expects deliveries of some eight A330/340s, 14 A320s and a handful of regional jets that will lift capital spending towards the €2bn mark. Although it is likely that operational cash flow will be hit, the group still had more than €4.2bn in cash at the year end (against €3.6bn in debt) – and more importantly has been able to tap the debt markets even in these troubled times (with among other things a successful €600m private placement in February) – and aims to maintain a minimum cash balance of €2bn. Air Berlin’s full year 2008 results show the first full year of the integration of LTU (although in 2007 they produced proforma figures for what the numbers would have been had LTU been integrated for the full year at that time). In 2008 total revenues grew by 34% to €3.4bn, EBITDAR by 26% to €476m (producing a margin of only 14%) while net losses came in at €75m, down from a profit of €21m last (or what could have been a proforma loss of €40m, depending on how you look at it). On a like–for–like basis revenues and EBITDAR were up by 7% and 12% respectively.

The company had already started reducing its growth rate as it came into 2008 (from what was for it a dire 2007) with the aim to improve underlying profitability, before the damage created by the significant increase in fuel costs. This it intensified in the middle of the year, through the introduction of its “Jump” earnings improvement plan. The company tightened up its route network, withdrawing from various loss–making routes and realigning capacity (including running down its operations at Stansted and closing down the recently opened Düsseldorf–China routes). It cut back use of wet–leased capacity and disposed of the F100 fleet earlier than originally anticipated (replaced with leased turboprops – pushing it even further away from the low cost model).

Full year capacity in ASKs fell by 4.9% year–on–year, while demand in RPKs fell by only 3.8% and it managed to push up unit revenues by a significant 12% year on year – although part of this was due to a drop in stage length. Average income per passenger came in at €108.70, up by more than 6% year on year (at more than twice that of Ryanair, which is hardly low–cost?). As one of the few former charter carriers to have transferred to scheduled operations, charter remains an important element of the group, but now only accounts for 40% of revenues (down from 43% in 2007), while of the remaining seat sale business, Air Berlin has been actively chasing corporate and travel agency distribution – with internet sales falling to 42% of the total in 2008 (down from 46% in 2007). Company travel agreements are key to accessing German corporate travel, and Air Berlin has been able to increase the number of such agreements fourfold in the past five years – with revenues from that source growing by 2.5 times to more than €600m p.a. – equivalent to a third of its scheduled seat sales.

Unit costs were up by 12% on a like for like basis – with total DoCs up by 8%. Naturally a large part of this was the fuel bill – up by nearly 20% to €874m (after hedging gains of around €180m – and, like many, although Air Berlin had a good hedge position for most of the year the final quarter would have seen out of- the–money contract losses). However, even without this fuel increase, underlying unit costs were still up by around 7%; the biggest contributor being a 6% increase in wage costs, reflecting union wage agreements a year ago. There was a noticeably high jump in consultancy fees – presumably reflecting the time and effort in trying to pursue the aborted Thomas Cook/Condor deal last year.

Naturally at the moment Air Berlin has little visibility for full 2009. The management stated its intention to be able to produce an improved operating profit for the full year while warning that there would be heavy negative effects weighing on the first quarter. The company has cut back capacity significantly. On domestic routes it is increasing capacity by around 2%, increasing gauge on the denser routes and phasing in more Dash–8s for secondary routes. It will be cutting further (or, as they say, optimising) its intra–European scheduled business with an anticipated 3% decline in capacity, although it did suggest that it will be strengthening the domestic Spanish feed into the Palma hub (it is still difficult to believe that an intra–European hub can really work, low–cost or not). The charter operations are being cut back by around 8% — apparently in line with tour operator expectations. On the former LTU long–haul network the company is slashing capacity by around 27%.

To accommodate the lower growth expectations the company has a reasonable level of flexibility in the number of existing fleet of 125 aircraft coming off lease, but there are another eight A320s and six 737s due for delivery this year along with eight Dash 8–Q400s, and it will have to find lessees to take on some of the spare aircraft (and Air Berlin still has 108 A320/737s on order up to 2014 and a further 25 787s from then on). Meanwhile, the deal with TUI will be bringing in another 17 aircraft along with the routes that the former HLX operated in competition — but at least cutting out a competitor, and having persuaded TUI to encompass the majority of any restructuring prior to the deal, should mean that it is not dilutive. Meanwhile with €270m cash in hand at the year–end (€200m down on a year ago) against balance sheet debt of €1bn and equity of €390m (unless you want to knock off the €310m intangible assets on the balance sheet), the modest cash injection from TUI for a 20% stake should come in useful.

Germany is a unique domestic market in Europe: the two major players may hope that this latest round of consolidation will continue to help keep out the encroachment of true low cost competition. Air Berlin has at least appeared to cut back its long–haul ambitions (at least until CEO Hunold manages to get the LTU employees to succumb to his wishes for integration as he did at dba), which could mean, as the Air Berlin management has suggested in the past, that there can be a “comfortable” duopoly domestically while Lufthansa continues to build its side of the Maginot line in its fight against its franco–hollandaise rival.

| Total | % | |

| Lufthansa | 196 | 47.6 |

| Air Berlin | 109 | 26.5 |

| TUI | 45 | 10.9 |

| Condor | 25 | 6.1 |

| Other | 37 | 9.0 |

| Total | 412 | 100.0 |