Air Arabia: classic start-up, but facing diversions

April 2008

Air Arabia is a classic start–up success story. Staring with initial equity of AED50m ($14m) at the end of 2002, it is currently valued at about AED8.3bn ($2.3bn) on the Dubai stock–market, with a p/e of about 22.

Air Arabia was the first and to date the only flag carrier to be designed on LCC principles. The Emirate of Sharjah, just north of Dubai in the UAE, instigated the airline project in late 2002 by establishing a project team led by Adel Ali, who became the airline’s chief executive. From a blank piece of paper Aviation Economics developed the business plan, and the first flight took off in October 2003. (AE hasn’t been involved with the airline in recent years and so, alas, can take no credit for its performance, although the principles of the business plan have been very closely adhered to and the original operational and financial projections were pretty accurate.)

2003 was a good time to set up an LCC in the Gulf. Excellent lease rates were available, the fuel price was still low and flying crews were fairly easily available. Air Arabia was sponsored by its own low cost, much underutilised airport at Sharjah, which is physically close to Dubai, although traffic can be horrendous during peak hours. Sharjah Airport Authority originally owned 40% of the airline, and the initial funding of AED50m was provided by the airport and the Department of Civil Aviation. And none of the incumbent airlines took Air Arabia seriously.

Traffic conditions too favoured the airline. Dubai was entering into its phase of super–growth, boosting the migrant worker population (mainly from the Indian subcontinent but also from countries such as Egypt and the Lebanon) that form the core of Air Arabia’s market. Air Arabia also benefited from the increase in tourism within the Gulf region as Dubai advertised its glittering attractions.

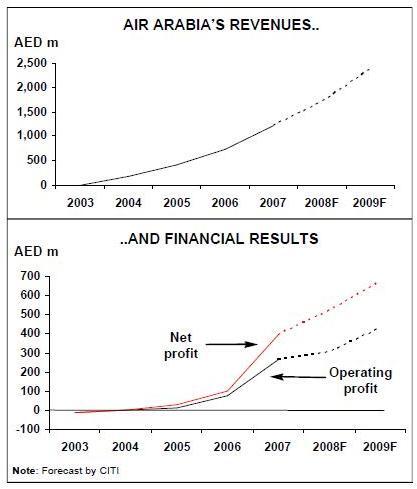

Air Arabia has been cash–generative from the first full year of operation. For 2007 its operating profits are estimated at AED260m ($72m) on revenues of AED1.28bn ($350m), a Ryanair–type margin of 20%. Net profits were actually higher because of interest income and because the company accounts for rebates from Sharjah airport as a financial income figure — at AED390m (£108m) net profits represented a remarkable 31% of revenues. No taxes are payable in Sharjah (personal, corporate or other), which of course greatly helps the cost structure (as does Dubai’s identical regime for Emirates or Abu Dhabi’s for Etihad). Dividend policy is to pay 25% of net earnings to shareholders, which totalled AD97m ($27m) for 2007.

Projections produced by Citigroup Financial Markets in a detailed and insightful review* of the carrier published in February indicate a 38% per annum revenue growth to 2010, with profit margins just easing slightly.

Air Arabia’s balance sheet is also extremely strong, with no debt in its AED5.4bn ($1.5bn) capitalisation, following its successful IPO; cash and equivalents at the end of last year amounted to AED3.3bn ($0.9bn).

Last year Air Arabia found itself in a position to tap the Middle East financial markets' appetite for airline investment.

Through a private placement in March and an IPO in June 2007 on the Dubai Financial Market, AED 3.27bn ($890m) was raised in new equity, which diluted the Sharjah state’s stake from 100% to 18%. Other founding investors and staff now have 12%. The remaining 70% is mostly held by Middle Eastern financial institutions, notably Abraaj Capital with about 17% and Al Maha Holding with 9%.

Around AED1.7–2bn of the new funds are earmarked for fleet expansion — specifically deposits and PDPs on the 34 A320sthe airline has on order; total aircraft–related expense for the period to the end of 2102 amounts to about AED3.8bn ($1.1bn). AED600–700m will be used for investment in expanding the base, developing maintenance facilities and building a new hotel at Sharjah airport. The remainder — about AED1bn — is linked to "strategic investments" in airline joint ventures and base expansions (see below).

Arabian LCC model

The challenge for Air Arabia has been how to adapt proven LCC tactics — point to points services, internet distribution, high asset utilisation, airport cost minimisation, etc — to Middle East conditions:

- Aircraft utilisation at Air Arabia averages 14.5 hours a day compared to a global average of 8.6 hours for A320s. To achieve this it exploits the fact that Sharjah — like other airports in the region — operates 24 hours a day, so it can schedule an overnight trip to, for example, Colombo in Sri Lanka after operating flights in the Gulf region throughout the day. Dispatch reliability at 99.8% is one of the highest, if not the highest, in the industry, and is the result partly of having a fleet that is under two years old on average as well as the excellence of its line maintenance, for which it has received awards from Airbus.

The airline has also set up a joint venture with HAECO, the Hong Kong–based engineering company, to eventually perform C checks at Sharjah.

- Aircraft are configured with 162 economy seats (a bit below the maximum for A320), which allows a 32" pitch, which is slightly better than the average space for economy products in the region. Load factor is around 85%. Meals are sold on board but there are no alcohol sales as Sharjah is a dry state, which limits ancillary income (about 3% of turnover as against 10% at easyJet).

- All the airports Air Arabia flies to are primary (generally there are no alternatives) and it pays rack rates there. But it has a very important symbiotic relationship with Sharjah airport, from which it receives a waiver on landing fees and ground handling charges equivalent to about AED30m in 2007. It would be very difficult for a competing airline to set up a base at Sharjah.

- With credit card and computer usage much lower among Air Arabia’s clientele than in Europe, internet sales are much lower than for European LCCs, but they are growing rapidly — from about 30% of revenue in 2007 to a budgeted 50% this year. About 60% of sales were made through travel agents in 2007, but with zero commission rates (apart from some override agreements) — the travel agent uses essentially the same online booking process as an individual traveller and charges a fee to the passenger for the service.

The other 10% was sold via a call centre, through sales shops in the UAE and through an arrangement with the local post office.

- Air Arabia has had to operate in a regulatory regime that is largely based on bilateral ASAs, although the GCC (GulfCooperation Council) states do have an open skies regime. But Air Arabia is also a flag–carrier of the UAE (along with Emirates, Etihad and RAK), which greatly facilitates its negotiating position. Air Arabia currently flies to 37 destinations in the Gulf, the Indian subcontinent, eastern Mediterranean, east Africa, Iran and central Asia, carrying 2.7m passengers in 2007. Its fleet of 11 A320s is expected to grow by about three leased units a year to 2012, when deliveries start of the 34 units (plus 15 options) ordered last year. With the rapid softening in the aircraft lease market, Air Arabia has the possibility of growing much more quickly if it wants to.

There would appear to be plenty of potential for developing business from the Sharjah base, both through increasing frequencies and via adding new points — as Citigroup points out, its existing network of 21 countries contain a population of 1.7bn. However, the competitive environment in the Middle East is changing, which seems to be causing a variation in its strategy.

New competitive threats

A disturbing development for Air Arabia was the announcement last month that Emirates had decided to set up its own low cost subsidiary in Dubai, with a target market of destinations with 4.5 hours of its base — i.e. identical to Air Arabia’s market. Details are not yet available but it will be based at the low–cost terminal at the new Jebel Ali super–airport and will probably start operations in 2009 with narrowbodies.

The new carrier will face the usual set of problems — risk of cannibalising traffic from Emirates, employee friction between the two airlines, differentiation of products and so on — but any entity with the backing of the Emirate of Dubai is going to be very powerful. Indeed the Centre for Asia Pacific Aviation believes it is only a matter of time before the A380 is deployed at the airline, with ultra–dense configurations of up to 1,000 seats.

From Saudi Arabia the two newly licensed domestic carriers — nas air and Sama — also have international expansion ambitions, especially to Dubai and Sharjah. They operate under the regulatory regime in Saudi Arabia (including the obligation to serve public service routes and economy fare caps), and are in competition with Saudia, making it very difficult for them to make any money in that market. They could be allowed to start international scheduled services next year or just expand their current international charter flights, which would be a threat to a key growth market for Air Arabia.

Jazeera Airways, based in Kuwait, has had a similarly successful growth to Air Arabia (with a more full service product) and now is encroaching on Air Arabia’s territory by establishing a second base at Dubai and using its fifth freedom rights to offer flights to India. When it moves to Jebel Ali it too is expected to expand (it has 30 A320s on order) and it could target the 15% of Air Arabia’s passengers who are business travellers, although it will not be able to match Air Arabia’s cost structure.

And then there are the Indian start–ups like GoAir, IndiGo and SpiceJet, which are desperate to expand into the international market that has been reserved for Air India/Indian Airlines and Jet Airways. Indian government policy is to liberalise international service but the bureaucracy is — as usual — taking a long time to sort out the details (such as the length of time flying domestically before international service is permitted, the required size of fleet, etc.), and there is a suspicion that protecting Air India’s long–planned privatisation has again become a priority. Nevertheless, the threat to Air Arabia is that Indian airline capacity has been artificially restricted on routes to Sharjah and Dubai. Although Air Arabia has benefited from by capturing a major portion of the market (almost 40% of Air Arabiatraffic is now to the subcontinent), this situation could soon change. On the other hand, greater liberalisation would open up new routes for Air Arabia itself.

In response, Air Arabia has decided to add new bases. It is in the process of setting up a base at Rabat, the capital of Morocco, initially with two A320s but with a plan — according to Citigroup — of expanding ultimately to 20 aircraft. It will take over the management of Régional, a mostly domestic turboprop operator, which was for years the only local alternative to the flag–carrier RAM. Rebranding as "Air Arabia Maroc" is likely The idea is to develop a network into other Arab countries in the Maghreb and the Middle East with which Morocco has open skies agreements. As Morocco — through its liberal bilateral with the EU — is in effect part of the EU in aviation terms, it could also offer services to, for example, France, building on Régional’s flights to Spain and Portugal.

Following the signing of an open skies agreement between the UAE and Nepal, Air Arabia entered into a joint venture called FlyYeti with Yeti Airlines, a domestic turboprop operator. Flyyeti is based at Kathmandu and has one wet–leased 737- 800 at present, although again Air Arabia is expected to transfer a couple of A320s to Nepal.

The analogy drawn with the European LCCs is that this strategy is the equivalent of easyJet or Ryanair moving to continental European bases as they outgrew the UK/Ireland markets. But this analogy is very strained. First, there are huge distances between the bases: Rabat is more than 6,000km from Sharjah, further than, say, the distance between Paris and New York. Second, Morocco and the UAE are of course both Arabic countries but their cultures and economies are very different. And Nepal is even more different.

Third, there are few if any network synergies. Flyyeti intends to fly Middle East migrant workers to India, but it seems unlikely that connecting on to the UAE on Air Arabia services from there is a viable strategy. Similarly, there appears to be an expectation that Moroccan traffic will connect to the Air Arabia network at some point in Libya or Egypt. But the dominant Moroccan traffic flows are not west–east but south–north, where Air Arabia Maroc will find itself in uncomfortable competition with Air France/RAM — two airlines that have always been careful to control key French routes — plus local LCCs like Jet4You and potentially with Ryanair, which plans to expand strongly into Morocco from its Marseilles base.

It is difficult to assess whether these new bases really are central to Air Arabia’s strategy or are experimental tactics that are low risk for an over–capitalised airline. In Ryanair terminology, however, it doesn’t look in this instance that Air Arabia is "sticking to its knitting". On the other hand, Air Arabia may have found a new revenue source from franchising its LCC brand, something that easyJet has considered but never implemented.

There are also other ways that Air Arabia could respond to the changing competitive threat at Sharjah from possible LCC overcapacity. One way might be to consider a merger with one of the new entrants; for example, Abraaj Capital has significant stakes in both nas air and Air Arabia.