WestJet: The Canadian overachiever

April 2008

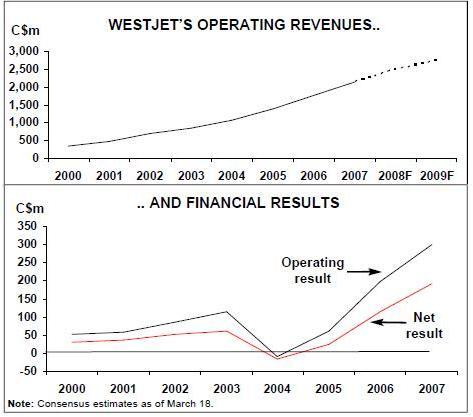

WestJet, the Canadian LCC, is on a roll: eight consecutive quarters of record earnings, industry–leading financials in 2007 and continued 16%-plus capacity growth in 2008. Why is the Calgary–based carrier outperforming its peers? What strategies is it deploying to ensure future success?

While WestJet has been profitable throughout its 12–year history (except for a small operating loss in 2004), in the past two years it has suddenly emerged as one of the most profitable airlines in the Americas. Just as the other LCC high–flyers in the region — Southwest, JetBlue and the Brazilian LCCs — have seen their profit margins fall due to fuel and other challenges, WestJet has seen the opposite: its operating margin increased from a negative 1% in 2004 to 4.4% in 2005, 11.3% in 2006 and 14% in 2007.

The margin improvement is all the more remarkable in light of WestJet’s continued brisk capacity growth. Its ASMs have doubled since 2003, even though in 2003 WestJet was already virtually a "major carrier" (under the US definition of annual revenues exceeding US$1bn). Its revenues have doubled in three years, from C$1.1bn in 2004 to C$2.2bn in 2007, making WestJet only about 20% smaller than JetBlue. (Of course, JetBlue has grown at a much faster rate overall.)

WestJet reported an operating profit of C$300m and a net profit before special items of C$181.3m for 2007, accounting for 14% and 8.4% of revenues. For the fourth quarter, the airline posted operating and ex–item net profits of C$73.4m and C$41.7m, respectively, on revenues of C$553.4m. The 13.3% fourth–quarter operating margin was the highest among large airlines in the Americas.

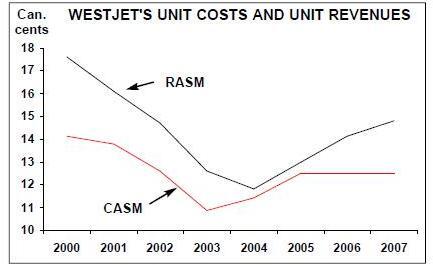

In the December quarter, WestJet managed to improve its load factor by 2.2 points (to 77.7%), yield by 3.2% and unit revenues (RASM) by 6.2%, despite 15.2% capacity growth. The airline was also able to limit the unit cost (CASM) hike to 2.3%, despite a 17% increase in per–litre fuel cost.

WestJet has been able to turn in such stunning results because of a rare confluence of special internal attributes and favourable external factors. The Calgary–based carrier has a great business model, capable management and some very clever strategies; however, unlike its peers south of the border, it has also benefited from favourable economic and competitive environments.

On the revenue side, WestJet has benefited from buoyant demand conditions in Canada, created by a strong domestic economy (with little sign of weakening so far), as well as a stable competitive environment — effectively a duopoly with Air Canada.

But WestJet has also been extremely adept at managing capacity and revenues. It has been able to add significant capacity without adverse effects on the load factor and yield. This has been achieved, among other things, through a seasonal aircraft deployment strategy, under which large chunks of capacity are shifted twice annually between the domestic market and the winter sun routes.

On the cost side, WestJet has benefited from the strengthening of the Canadian dollar particularly in the second half of 2007 (due to the strong economy and high oil prices, as Canada is a net exporter of oil and natural commodities). The C$ appreciated against the US$ by about 15% in 2007. Since about one third of WestJet’s total costs are denominated in US dollars or linked to US$ indices, the C$'s appreciation offset about 50% of WestJet’s fuel price hike and significantly reduced its aircraft leasing and interest expenses. But WestJet has also succeeded in keeping other costs in check, as indicated by the 2.6% decline in its ex–fuel CASM in the fourth quarter.

Favourable competitive regime

WestJet’s good fortunes are intrinsically linked to the major changes that have taken place in the Canadian aviation regime over the past decade. How many other LCCs around the world can boast a 35% share of their country’s domestic market? WestJet’s CEO Sean Durfy noted in a recent speech:"We are very fortunate that we have a duopoly in Canada and we have rational players in the marketplace today". However, the road leading to this point has been tough at times.

Launched in February 1996 by a team of Calgary entrepreneurs headed by its current chairman Clive Beddoe, WestJet was created essentially to replicate Southwest (with modifications) in Canada’s domestic market, which had been deregulated in 1988. Beddoe had the foresight to bring in one of the highest–calibre low–fare airline experts, David Neeleman, to provide the blueprint for a successful operation. Neeleman, who had co–founded Morris Air (which Southwest bought in 1993) and later founded JetBlue in 2000, also helped the WestJet founders raise funds and buy aircraft.

In its initial years, WestJet fought fierce battles with Canadian Airlines in the West but still managed to earn 10%-plus operating margins and go public, with a listing on the Toronto Stock Exchange, in July 1999. WestJet was one of the factors that led to Canadian’s downfall.

Air Canada’s acquisition of Canadian in January 2000 gave WestJet a major growth opportunity. The airline, which had hitherto focused on the western region, expanded into eastern Canada, developed a new hub in Hamilton (Ontario) and initiated plans to replace its fleet of old 737–200s with new 737NGs.

But the early years of this decade brought new challenges. First, there were the effects of 9/11, even though air travel demand in Canada remained stronger than in the US and the competitive environment was certainly healthier as a result of the 2000 industry restructuring.

Second, there was a surge in competition after the Canadian government stated in 2002 that it wanted Air Canada’s domestic market share reduced below 80%. Several new low fare carriers (CanJet, Jetsgo, etc.) entered the market and Air Canada set up new low fare and regional subsidiaries. This led to fare wars, which further worsened after Air Canada filed for bankruptcy in early 2003. As a result, WestJet posted small losses for 2004 and the first quarter of 2005.

But the newcomers were too small, poorly funded and lacking in focus to have staying power. Jetsgo ceased operations in March 2005, CanJet withdrew from scheduled service in September 2006 and Harmony ended scheduled flights in April 2007.

Jetsgo’s demise led to an immediate substantial improvement in the domestic revenue environment, enabling WestJet to return to decent profitability in the subsequent quarters.

Importantly, the demise of the smaller carriers also solidified WestJet’s position as Canada’s "second–force" airline, part of a domestic duopoly with Air Canada, which had emerged from a successful bankruptcy reorganisation in September 2004.

Air Canada’s contraction in bankruptcy had given WestJet added opportunity to build domestic market share. In 2004 WestJet also entered the Canada–US transborder market and in 2006 it added service to the Caribbean and launched WestJet Vacations.

In the past decade WestJet has grown its domestic market share by 2–3 percentage points each year. Because of its prominent position, it has a better business mix than the most up–market US LCCs (passengers travelling for business purposes accounted for 45% of its total traffic last year). Competition with Air Canada, which is also doing well financially, is totally rational these days.

The only question is: can a duopoly last in a deregulated market? Probably yes — as long as low fares continue to be easily available in most markets — because Canada is not a very large domestic market; at 64m passengers in 2005, it is less than one tenth of the size of the US domestic market.

Maintaining a cost advantage

Keeping costs low has been the key factor behind WestJet’s financial success. In the past two years, total CASM has remained flat, at 12.5 Canadian cents, while ex–fuel CASM has declined by 1.2%, from 9.16 to 9.05 Canadian cents. These trends are much better than those experienced by US carriers.

However, the bulk of the CASM improvement has come from economies of scale (robust ASM growth) and increased average stage length, rather than ingenuous cost–cutting initiatives. WestJet’s average stage length increased by 6.7% in the past two years, from 802 to 856 miles. The stage length has more than doubled since 2000 (when it was only 419 miles) as the airline has expanded transcontinental, Canada–US and Canada–Caribbean flying.

Increased longer–haul flying has also boosted average daily aircraft utilisation, which increased from 11.8 hours in 2006 to 12.1 hours last year. WestJet hopes to achieve 12.5 hours in 2008 through the addition of new Caribbean services, as well as more red–eye and tail–burn flying.

Of course, switching from the 737–200 fleet to 737NGs produced significant cost savings. WestJet uses blended winglet technology on its 737–700s and 737–800s and other fuel conservation measures, including new technology pioneered by Alaska Airlines that helps choose the most fuel–efficient flight paths.

WestJet believes that it enjoys a 30–40% cost advantage over Air Canada and is looking to at least maintain it. CFO Vito Culmone said at a recent conference that the goal is to achieve the "lowest sustainable cost per ASM in North America" but that WestJet is "not there yet", even after adjusting for the excise taxes on fuel and other additional charges that that Canadian airlines have to pay (compared to their US counterparts).

Good revenue management

Airlines in Canada have implemented a steady stream of fare increases in recent years. They have got away with it without adverse impact on demand, in the first place, because of the healthy economy and strong consumer confidence, because people feel that they can afford to fly. But how does that fit in with WestJet’s stated Southwest–style strategy of stimulating demand with low fares? The answer is good revenue management: knowing where and when the market needs to be stimulated with lower fares and when fares can be raised to improve yield.

WestJet’s management argued at the carrier’s fourth–quarter earnings call in February that there was still "great, great, great pricing" available on certain days of the week and on many routes. Also, WestJet continues to stimulate the market — the best examples currently being St. Lucia, Quebec City and Atlantic Canada — as it is still in the process of shifting market share from Air Canada.

WestJet has not abandoned its low–fare strategy; it has simply become very sophisticated in revenue management. Like other LCCs in the Americas, it has experienced severe revenue management problems in the past and has successfully upgraded its systems.WestJet currently generates ancillary revenues from fees associated with itinerary changes and excess baggage, as well as from the sale of food, pay–per–view movies and headsets on–board aircraft. Revenues from such sources grew by 30% to C$95.7m in 2007 — just 4.4% of total revenues — or C$7.65 per passenger. Like other LCCs in the region, WestJet views ancillary revenues as a promising growth area, because much of it is very high–margin business and can even enhance customer experience. Some of those opportunities will be realised as the stage length increases and at WestJet Vacations, where customers already purchase more than just an air ticket.

The evolving business model

WestJet’s business model was originally a close replica of Southwest's: 737s, point–to point, single–class, no–frills service in niche markets; focus on under–served and overpriced markets; a fun and friendly image and an informal, people–focused culture. The main differences — WestJet’s smaller size, lower flight frequencies and supplemental strategy of operating charters — reflected the much smaller size and dispersed nature of the Canadian domestic market.

While much of the original model remains intact, since 2000 WestJet has moved towards the JetBlue model as it has made the rather dramatic transition from a small western- Canada focused regional airline into a nationwide operator with one third of the domestic market and growing international operations.

Today WestJet has a very up–market product, more similar to JetBlue’s than Southwest’s. It offers LiveTV (and has secured agreement to be the only airline to offer that system within Canada until the end of 2009), four pay–per–view movie channels on its entire fleet, leather seats with a generous seat pitch and lounges at four airports (operated by a third party and available for a fee). Like many other LCCs these days, it now offers the full range of booking channels. That said, WestJet appears to go a step further than its peers in trying to ensure a "tremendous, world–class guest experience" — or at least its management sounds very scientific about it. CEO Durfy explained recently that guest experience has two components:

"functional" attributes (on–time performance, baggage delivery, completion rates) and "care" attributes (how passengers are treated, having empathy when something goes wrong, saying sorry, smiling, etc.). While WestJet certainly continues to deliver in terms of the functional attributes (it ranked among the top five in the North American airline industry in 2007 in terms of the three main DOT operational metrics), the company believes that the more tangible "care" attributes are more important for creating customer loyalty. The numerous initiatives in that area include a "Guest Experience Matters" or GEM Team to facilitate cross–functional planning, decision–making and quality implementation.

WestJet is seeing a positive impact from those and other brand development efforts in its customer surveys, which show that over 90% of its passengers will recommend it to others. The positive effects are especially strong in eastern Canada (except Montreal for some reason), where WestJet is expanding its footprint.

One of WestJet’s biggest accomplishments is that it has come closer than any other LCC to emulating the way Southwest treats its people. It recruits service–oriented workers, trains them well and motivates them to outperform through productivity and profit–based incentives. The workforce benefits from generous profit–sharing and stock ownership programmes. Last year the company paid C$48.6m in profit–sharing, with WestJetters (as they are called) receiving on average 16.9% of their base pay as profit sharing. At year–end, 83% of eligible employees participated in the share purchase plan, to which they can contribute up to 20% of their base salaries, with the company matching every dollar contributed (employees must hold the funds in the plan only for a year).

Last year the average employee contribution was 14% of base salary and the company’s matching expense was C$35.4m.

CEO Sean Durfy noted at a recent investor conference that financial executives' eyes tend to glaze over when one talks about people but that corporate culture really is the key to financial success. "My background is in finance, but the true success of our company is around the culture", he noted, explaining that it is really about "aligning the interests of the people with the interests of the company" and that having a high employee share ownership creates a different dynamic in a company.

"When you own something, you treat it differently."

This characteristic of WestJet has received public recognition. The airline recently won Canada’s "Most Admired Corporate Culture" award for the third year in a row. The award is presented by Waterstone Human Capital and is based on interviews with chief executives at Canada’s top 500 companies.

Route network strategy

Much of WestJet’s initial financial success was due to its relatively conservative (by LCC standards) growth strategy of adding only 3–5 aircraft per year. After four years, it operated only 15 aircraft, serving 12 cities primarily in western Canada.

Eight years on, following major expansion first into eastern Canada and then in the US and Caribbean markets, WestJet operates a 73–strong fleet, serving 45 cities (as at the end of March). The scheduled network includes 26 points in Canada, 12 in the US (including Hawaii), two in Mexico and five in the Caribbean. Including the charter business, WestJet flies to 68 destinations in 14 countries.

The stated long–term objective is to achieve 10% annual ASM growth. However, barring a severe recession, growth in the next couple of years is likely to exceed that as WestJet takes advantage of the strong demand conditions and the stable competitive environment in Canada. The airline is confident that it can sustain a higher growth rate because of its good cost controls, revenue management skills and the successful seasonal aircraft deployment strategy. The current plan is to grow ASMs by 16% in 2008 (same as last year), with the first half of the year seeing 18–19% growth, though WestJet is obviously keeping a close eye on the economy.

But where will all that growth take place? The near–term is not likely to see major geographical shifts; each of WestJet’s three distinct markets — domestic, US–Canada and Caribbean/Mexico — will see capacity addition. Last year the airline indicated that about half of its future growth would be international (including the US).

- Domestic routes WestJet still sees good domestic growth opportunities. Markets such as Kitchener- Waterloo (Ontario), which was one of three new domestic cities added in 2007, have quickly become very profitable (eastern Canada markets tend to have more business traffic). WestJet will add Quebec City as its 27th Canadian point in May, initially with service from Toronto. The airline believes that it could serve another 6–7 domestic points. In addition, there are opportunities to increase frequencies; for example, WestJet still has only five daily flights in the important Toronto- Vancouver market in the summer, compared to Air Canada’s 20.

The airline believes that its strong brand, additional destinations and frequencies, continued schedule refinements and new interline relationships will help capture another ten points or so of domestic market share, to boost the share from the current 35% to 40- 50%.

- Canada-US market WestJet entered the scheduled transborder market in the autumn of 2004 with six leisure–oriented routes to the West coast and Florida mainly out of Calgary. Within months the Toronto–Los Angeles and Calgary–San Francisco operations were terminated, but since then the airline has added a few more destinations in Florida and the West, as well as three points in Hawaii. The US operations have not been a blazing success because of difficulty in developing US–originating sales.

WestJet currently has only 7% of the scheduled transborder market, with Air Canada accounting for 38% and US carriers 55%.

But WestJet believes that it can grow its transborder market share to 15–20% in the next four or five years. It hopes to both stimulate the market and take share from US airlines, once it starts expanding into business markets in the US — something that will be possible when it gets its US point–of–sale developments fully up and running. One major milestone, accomplished in early March, was getting schedules, fares and inventory fully available on Expedia in the US. WestJet is launching its first business–oriented US route, Calgary–Newark, as a seasonal service in June and may add another US business destination this year. It expects to keep adding 1–2 such points each year in the next four or five years.

- Caribbean/Mexico WestJet ventured into the Caribbean market with scheduled service to Nassau (Bahamas) in 2006. The huge success of that initial foray and the new WestJet Vacations unit encouraged the airline to add six more destinations in 2007, in Jamaica, Dominican Republic, St. Lucia and Mexico.

The airline has only dipped its toe in the Canada–Caribbean/Mexico market (1% market share) but believes that it can capture a 10–20% share. CFO Vito Culmone suggested recently that WestJet could easily add another 10 destinations in that region, as "quite frankly, we can’t get there quickly enough to satisfy demand". Many of the US LCCs have also found the Caribbean market very attractive, with JetBlue even reporting year–round demand in some markets.

Caribbean/Mexico operations are ideal for WestJet because the Canadian domestic market is quite seasonal, with demand weakening significantly in the harsh winter months. Flights to the sun destinations (including Florida) have transformed the January quarter from WestJet’s weakest to its second most profitable period.

In the past three years, WestJet has deployed a highly successful strategy of moving capacity between the sun destinations and the domestic market, depending on the season. About 25% of its capacity gets shifted around like that. The result is that scheduled international operations account for as much as 25% of WestJet’s total ASMs in November–April but only about 5–7% in May–October. If charter services are included, international operations account for as much as 35% of WestJet’s total ASMs in February and March.

WestJet has always operated charters to improve aircraft utilisation in off–peak periods. Since 2003 it has also provided aircraft and crews to Transat, Canada’s largest tour operator, under a contract that has been renewed twice and is currently valid until February 2010. The contract makes a useful revenue contribution. WestJet’s management insists that, despite the airline’s own substantial plans for Caribbean expansion and WestJet Vacations, the relationship with Transat remains strong.

International alliances are one particularly promising future growth avenue for WestJet, given its sizeable domestic network. By some estimates, interline or code–share deals could bring in potentially $400m in incremental revenue annually for WestJet.

Like JetBlue, WestJet has talked about such alliances for years but has been hindered by technological constraints. In the past year, WestJet has had a small interline deal in place with Air China, which has worked well but has mainly been useful in ironing out some of the operational kinks related to an interline agreement.

After spending many frustrating years trying to deploy the aiRES reservation system, which would have facilitated interline and code–share deals as well as US point–of sales, last year WestJet extricated itself from that contract (incurring a C$32m impairment loss) and instead focused on upgrading its existing system. The airline says that the current system is now "fully capable of meeting our strategic goals for 2008" and that it continues to review options for a new reservation system for the longer term.

Separately, the management has said that the airline is hoping to add two new interline (though not code–share) partners in 2008. The new partners could be in Europe or Asia, or in the US. BA is known to be interested (it first approached WestJet in late 2006 when it began London–Calgary operations), but then again WestJet executives have indicated that they would prefer philosophically aligned partners. CFO Culmonenoted at a recent investor conference that "there are a few airlines, especially in the US, that we are philosophically aligned with". Is a WestJet/JetBlue alliance a possibility?

Fleet plans

WestJet has spent around $2bn since 2001 on renewing its fleet. The last of the 737–200s departed in early 2006, about two years ahead of schedule. The current fleet of 73 737NGs is among the youngest in North America, with an average age of 3.2 years at the end of 2007.

After originally hoping to standardise the fleet on the 737–700 (the type Southwest has chosen as its workhorse), WestJet realised that the characteristics of the Canadian market (large distances between major cities, some high–density short and medium haul markets) required it to operate more than one aircraft type. The current business plan includes three 737 variants: the 119–seat 737–600, the 136–seat 737–700 and the 166–seat 737–800.

After placing another major 737–600/700 order (20 firm plus 30 options) in 2007, at year–end WestJet had 46 aircraft on firm order. This will take its fleet to a minimum of 116 aircraft by the end of 2013 (91 -700s, 13 -600s and 12 -800s, though there is some flexibility to switch between variants).

There are likely to be option conversions. The management indicated recently that the market share targets that they have set for the domestic, Canada–US and Caribbean/Mexico operations would require WestJet to grow its fleet to 116–130 aircraft by 2013.

The fleet will grow at a rate of 6–9 aircraft per year. This year WestJet is taking seven aircraft (five 737–700s and two 737–800s), to bring the fleet to 77 at the end of 2008.

Nearly all of the 2008–2011 deliveries are taken on operating lease — because Boeing’s order books have been full in recent years — but all of the 2012–2013 arrivals will be purchased.

This means that the total 46 firm deliveries in 2008–2013 will be split evenly between purchases and leases, enabling the company to maintain its desired 65%/35% owned/leased ratio.

Prospects

WestJet’s stock plummeted by 24% in the first two weeks of this year in response to sudden (misplaced) worries that the Canadian economy and airline sector were poised for a downturn. Although the share price has somewhat recovered, at the end of March it was still 16–17% below the December level, as fears have persisted that Canada could eventually follow the US into a recession. The stock looks undervalued and therefore remains on the "buy" lists of many analysts, though almost an equal number have a "hold" rating on it.

Most analysts see continued healthy profit growth for WestJet in the foreseeable future. The current consensus estimate is a 14% increase in per–share earnings in 2008, followed by a 13% increase in 2009. Revenues are projected to grow by 16% this year and 11% in 2009.

As of April 3, when WestJet reported its traffic statistics for March, there was no sign of any weakening of the buoyant demand conditions enjoyed by Canada’s airline sector. WestJet achieved a stunning 86.6% average load factor in March, despite 19.6% capacity growth. The load factor reflected the successful seasonal aircraft deployment strategy and was up 1.4 points in part because of the early Easter. Unit revenues showed significant year–over–year improvement. Also, advance bookings to the new cities to be added in May and June were strong.

If the Canadian economy remains healthy, WestJet should be able to continue to pass through some of the rise in fuel prices to customers, and the strength of the Canadian dollar will also mitigate some of the impact. But should the going get tough, WestJet has ample cash reserves (C$654m at year–end, about 30% of 2007 revenues) and a strong balance sheet to cushion the impact. Of course, the large cash balance could come in handy if weakening North American airline industry conditions yield some opportunities for the low–fare carrier.