United Airlines: Financial vote of confidence

April 2006

United’s parent UAL Corporation received what was effectively a strong vote of confidence from the financial community when it emerged from a three–year Chapter 11 reorganisation on February 1. Banks had been ready to provide twice the exit financing it needed (though that is not entirely surprising since it was all secured debt). Rating agencies immediately gave the company credit ratings that were higher than those of other solvent network carriers. Many stock market analysts expressed confidence about the company’s prospects — although some initiated coverage of UAL with a "sell" recommendation, it was only because bullish investors had already driven the share price many times higher than expected.

Yet, despite the $7bn cost cuts and other Chapter 11 accomplishments, United did not get its unit costs below the typical legacy carrier range. The airline closed the gap with American and Continental but made no further headway against LCCs — something that one would have expected it to do in bankruptcy.

Also, despite the extensive Chapter 11–facilitated debt and lease restructuring and the shedding of pension obligations, UAL still has a heavily leveraged balance sheet.

United also has a history of labour strife — something that raises questions about its corporate culture, even though service levels have improved dramatically in recent years — and it has what can probably be fairly described as one of the least respected management teams in the US airline industry.

Recent years have seen a steady stream of warning signs, including frequent significant revisions of the business plan, three unsuccessful federal loan guarantee applications and persistently over–optimistic financial projections. Add it all up, and one wonders why the financial community likes United so much.

There is a simple explanation: United has an unrivaled global route network and one of the world’s best known brands. Because of those attributes, there was never any real doubt that UAL would not be able to emerge from Chapter 11. In January, when the exit financing commitments were being finalised, United was still forecasting an operating profit of almost $1bn for 2006 based on the price of crude oil falling to $50 a barrel. That forecast was prepared in mid–2005 and looked very unrealistic when oil was $60 and heading up. Why did United not revise the forecast? Because it did not need to — the banks were going to support it anyway.

But United now has lofty investor expectations to live up to. Does it have the right strategies, and will it have a sufficiently competitive cost structure, to build upon its assets?

United has offered two explanations for its higher than expected post–bankruptcy unit costs.First, it admits that it has a lot more work to do, particularly in terms of reducing non–labour, non–aircraft ownership costs. The management apparently did not have time to focus on the multitude of smaller items (operational simplification, schedule productivity and suchlike) in Chapter 11, and United was left behind as competitors implemented their own cuts. What are the prospects for achieving additional cost cuts?

Second, United believes that it can get away with a higher cost structure than competitors because of its ability to attract higher volumes of premium traffic. There is a sharp new focus on the business passenger with specific product offerings. Is this a wise strategy, given that the premium segment is shrinking?

But United is actually targeting multiple segments with a strategy described as "meeting distinct customer needs with differentiated products and services". The leisure segment is being catered for with Ted, the low–cost unit launched in 2004. All of this is in sharp contrast to what the rest of the industry is doing. With most airlines now opting for simplicity in their business models in order to contain costs, could United succeed with a complex and expensive model offering multiple brands?

There is considerable interest in UAL around the world also because all of its recent growth has focused on its global network. Can that continue, and where is United heading next?

The Chapter 11 reorganisation

UAL filed for Chapter 11 in December 2002 after failing to obtain federal loan guarantees on a proposed $2bn loan to help it recover from the effects of September 11. However, the airline’s financial problems began long before September 11 — largely as a result of the unusual ownership and governance structure introduced by the 1994 ESOP, which gave employees 55% of UAL’s stock and three board seats in exchange for a 15% wage cut.

The troubles started with the ending of the ESOP in 2000, when wages snapped back to the pre–1994 levels and all of the labour contracts became amendable. United subsequently became the first major airline to grant hefty pay increases to its pilots which, in combination with the wage snap–backs, led to a sharp hike in labour costs.

This coincided with a double–digit fall in industry unit revenues in early 2001, partly reflecting a sharp decline in business passengers using full fares, followed by the effects of September 11. But even before September 11 United was headed for a $1bn loss in 2001; as things turned out, the loss was $2.1bn.

UAL spent more than twice as long in Chapter 11 than originally expected — 38 months, making it the longest airline reorganisation in history. It was also the most expensive restructuring to date, with lawyer and consultant fees adding up to a staggering $337m (as of early March 2006).

The process took so long, first, because United lost another federal loan guarantee application in mid–2004, after which it targeted pension plans as part of an effort to secure exit financing from other sources. Second, partly reflecting the large size of the company, there were a large number of aircraft financings to renegotiate — some of those issues still remain to be resolved.

Third, there were tough and complex issues involved, including pensions, retiree medical benefits and municipal bond litigation. Fourth, the restructuring took place in an extremely difficult industry environment; United would have been ill advised to rush to leave the protections of Chapter 11.

On the positive side, UAL’s Chapter 11 was relatively peaceful. There were no strikes. All of the agreements with labour and other parties were consensual, rather than court imposed. Unlike US Airways, UAL raised no new equity; instead it obtained a $3bn secured debt financing, consisting of a $2.8bn six–year loan and a $200m credit line, from a bank syndicate led by JP Morgan and Citigroup. The loan, which is secured by substantially all of United’s available assets, was used to repay the DIP facility and ensure sufficient cash reserves.

UAL issued 125m new common shares, which began trading on the Nasdaq on February 2. Most of the shares went to the company’s former unsecured creditors, who recouped something in the region of 10–20 cents on the dollar in stock based on UAL’s $4.5bn valuation at the close of the first day of trading. Employees received 10m shares (8%), while another 10m shares were allocated to a controversial management incentive plan.

As a result of United terminating its defined benefit pension plans (the largest corporate–pension default in US history), The Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation (PBGC) became the largest UAL shareholder with a 20% stake. However, the PBGC immediately indicated that it would sell half of the stake. As part of the settlement, United also issued the PBGC $500m of convertible preferred stock and $500m of senior unsecured notes.

The key accomplishments of UAL’s Chapter 11 were the following: Traditional governance structure Chapter 11 formally ended the ESOP and its related strong labour representation on the board of directors, giving United a traditional governance structure. The board consists of five incumbent, five new and two labour directors, with no group enjoying special voting privileges.

Reduced debt and pension obligations The restructuring eliminated $13bn in debt and pension obligations, reducing UAL’s total liabilities from $29bn to $16bn. Pension obligations declined by $7bn (to just $100m), secured aircraft debt by $3bn (to $6.1bn), lease obligations by $3.3bn (to $3.5bn) and post–retirement benefit obligations by $2.6bn (to $2.1bn).

Cost reductions The Chapter 11 process resulted in $7bn in average annual cost savings from 2005 to 2010. Of that total, $3.2bn came from labour — $2.5bn from wage and benefit reductions and $700m from work rule and pilot scope clause changes.

The rest of the savings represented mainly future expenditures that were eliminated — productivity enhancements ($1.8bn), restructured United Express contracts ($520m), aircraft obligations ($850m) and pensions ($600m).

Reduced size of company While in Chapter 11, United reduced its fleet from 570 to 460 aircraft (19.3%) and its work force from 83,000 to 58,000 (30%). The decline in capacity (ASMs) has been much less (5.7% in 2002–2005, following a 9.7% fall in 2001–2002) because aircraft utilisation has improved. The airline eliminated numerous unprofitable domestic flights, returning aircraft to lessors and secured creditors, reallocating capacity to international markets and transferring some flying to regional partners.

A competitive cost structure?

United emerged from Chapter 11 with lower unit labour costs than its peers but similar total CASM. This was because in the three–year period other airlines tackled non–labour costs more aggressively and also negotiated some pay and lease rate reductions of their own based on United’s new lower rates.

According to Merrill Lynch analyst Michael Linenberg, who quantified the trends and the peer differences in his mid–February initiation report on UAL, United’s mainline labour CASM declined by an impressive 32% in the three years to 3Q05 (twelve months ended September 30). The latest figure, 3.06 cents, was similar to Continental’s but much lower than Northwest’s 3.90, American’s 3.46 and Delta’s 3.32 cents.

In contrast, United’s mainline ex–fuel non labour CASM has remained relatively unchanged. At 4.55 cents per ASM in the TME 3Q05, it was 2–15% higher than the other legacy carriers'. However, United looks high on this metric because it has the flexibility to do more outsourcing than the competition.

In the three–year period, United’s total mainline ex–fuel CASM declined by 18.4% to 7.61 cents in the TME 3Q05. This was much lower than Northwest’s 8.29 cents but 1–2% higher than the other carriers'.

United’s total mainline CASM fell from 12.03 cents in 2001 to 10.52 cents in 2003 and since then has remained in the low–to–mid 10s, despite the surge in fuel prices. The CASM is very similar to American’s and Continental’s but obviously well above the 7–9 cent LCC range.

The consensus in the financial community is that United should have accomplished more cost cutting in Chapter 11 in order to be competitive. However, opinion is divided on the potential implications.

On the negative side, competitors are catching up or even overtaking United. Delta and Northwest are both restructuring in Chapter 11, while American and Continental are pressing ahead with further cost cuts; they are believed to be aiming for ex–fuel CASM of around 7 cents, compared to United’s 7.5 cents in 2005.

On the positive side, United can now focus on cost reduction initiatives that Linenberg described as "low hanging fruit". In his estimates, if United reduced its ex–fuel, non–labour CASM to the level of American, that would be worth at least another $500–600m in annual savings.

So far United has identified productivity measures that will result in $300m of savings in 2006. The initiatives are in the areas of resource optimisation (de–peaking all hubs, tightening aircraft turns, improving schedule coordination), maintenance (streamlining processes, outsourcing, etc.), airport operations, call centres and distribution. United will be able to focus fully on the non labour issues, because its labour contracts will not become amendable until January 2010.

The labour savings are sustainable because there are no snap–back or re–opener provisions, though there is a provision for annual wage increases of up to 2.5%.

Multiple branding strategy

Much will also depend on the success of United’s new strategy aimed at improving revenue generation. The airline has gone further than the other legacy carriers in differentiating its product offering for customers in various segments and markets. The aim is to offer "the right product, to the right customer, at the right time".

In other words, United is going out of its way to retain both premium and lower–end customers.

Two new brands have been introduced while in Chapter 11: Ted, the low–cost carrier, and "p.s", a premium transcontinental service. United has also expanded its seven–year–old "Economy Plus" programme that offers 3–5 inches of extra legroom on all mainline flights. First–class seating has been added to more than 100 70–seat RJs operated by regional partners under a programme called "explus". At the other extreme, to reduce the cost of delivery to leisure customers, United has introduced various new fees to non–élite coach class passengers.

United is also relaunching its international first and business classes over the next couple of years. This will involve a $165m investment in new seats and in–flight entertainment systems. Ted operates in markets where low–fare customers predominate, such as those where United competes primarily with Frontier and Southwest, though the unit also acts as a feeder to mainline services. Ted is now present at all five of United’s domestic hubs, serving 20 airports in the US and Mexico with a fleet of 56 A320s. The all–coach aircraft have 18 more seats than United’s mainline A320s though now also offer "Economy Plus" seating.

United went against the industry trend when it launched Ted two years ago. In recent years other network carriers have decided that they are better off reducing costs throughout their system rather than setting up separate low–cost units — after all, virtually all of the domestic market is now low–fare. Delta, too, is now eliminating its low cost unit — it will start integrating Song’s 48 aircraft into its mainline fleet in May, adding first class seating but retaining Song’s entertainment systems.

United is encouraged by Ted’s ability to recapture market share and eliminate huge losses on many routes, which is attributed to cost advantages stemming from a larger number of seats per aircraft and higher aircraft utilisation. In the 12 months ended October 31, Ted achieved an 84% load factor and an operating profit even on a fully allocated basis.

Ted accounts for 17% of United’s domestic capacity and is a key element of the new strategy. However, United’s leadership has indicated that the unit may be approaching its optimum size and will not be significantly expanded.

United’s decision to retain and expand "Economy Plus" seating, which is complimentary to elite–level FFP members and full–fare passengers and can be purchased by others for $24-$99 per flight, is totally contrary to industry trends. Most notably, last year American undid a similar programme launched in 2000, saying that adding back seats raised annual revenues by $100m.

However, United saw "Economy Plus" upgrade revenues double last year and expects them to double again to $50m in 2006.

Critics contend that United is taking a big risk with the "p.s." brand, which offers a private–jet style luxury product on 757s in markets with "extraordinary premium cabin demand", namely New York to Los Angeles and San Francisco. But United has reported some early promising results, including a 13–point increase in the segment profit margin.

Adding first class cabins and "Economy Plus" seating to commuter affiliates' 70–seat RJs is also an interesting experiment — the first time anyone has tried it on such a scale.

These high–end strategies aim to address the problem of premium passengers defecting to corporate jets, as service standards on commercial flights have slipped — a sort of backlash against the commoditisation of air travel. New niche carriers like Eos, which is wooing transatlantic business passengers with a product that mixes corporate jet–like privacy with the luxury of a first–class cabin, are also trying to cash in on this trend (see briefing in Aviation Strategy, October 2005).

Of course, there has been the much stronger parallel trend of corporations and premium passengers becoming more cost–conscious and switching to LCCs or to coach class. In other words, the premium segment is shrinking.

Strategy decisions are obviously influenced by an airline’s strengths. For example, Continental, which has great hubs and has long enjoyed a revenue premium over competitors, is one of the few airlines that still offers hot meals on domestic flights.

By the same token, United is probably the strongest candidate to succeed with the premium segment–focused strategy, because its leading positions in powerful hubs, comprehensive global network and strong alliances give it the best potential to capture such traffic. It has some extremely valuable assets, including a Pacific route system, which accounts for 44% of US airlines' capacity in that region, and significant operations at London Heathrow, Tokyo Narita and Frankfurt — the world’s most attractive gateways with severe capacity restrictions.

It is indicative that, unlike some other legacy carriers in recent years, United has not closed any hubs. In the US, it operates major hubs at Chicago O'Hare, Denver and San Francisco and smaller ones at Washington Dulles and Los Angeles. Each of those was considered viable based on the size of the local market and United’s leading position.

United also noted recently that, despite the Chapter 11 cutbacks, at the end of 2005 it actually served ten more cities (a total of 204), including seven more international points, and operated 45 more routes (456) than three years earlier.

United was previously not able to maximise the potential revenue advantage because its service quality was inconsistent. However, the airline has made significant strides in that area. In recent years it has consistently ranked among the top three major carriers in terms of on–time performance and other key operating metrics.

This is helping it retain premium passengers and appears to be reflected in unit revenue trends — United’s mainline RASM has risen steadily since 2002.

Linenberg calculated in February that United enjoys a 7% length–of–haul adjusted passenger unit revenue (PRASM) premium over other network carriers and a 40% premium over Southwest, though he said it was hard to ascertain how much of the premium was due to passenger segmentation.

Linenberg suggested that the strategy could make United more vulnerable in the event of an economic downturn. This is because having fewer seats per aircraft reduces an airline’s flexibility to generate additional revenue.

There are obviously backup plans. According to Calyon Securities analyst Ray Neidl, United’s leadership stated in early April that if the revenue premium model fails, the airline would add back seats, which would reduce its ex–fuel CASM by 4- 5% (from 7.5 to 7.1 or 7.2 cents).

Growth plans and prospects

United’s growth in the next few years will be relatively limited because the airline does not plan to take any additional aircraft. After shedding 107 aircraft while in Chapter 11, United reached agreement with Airbus and engine manufacturers in January 2006 to delay, with the right to cancel, all of its A319 and A320 orders valued at $2.5bn. However, United still expects to grow its system mainline capacity by 2.5–3% in 2006 through improved aircraft utilisation. Measures such as reducing turnaround times, trimming scheduled block time and improving schedule coordination are expected to free up at least ten aircraft in 2006.

United has not disclosed more detailed growth forecasts, but most of the freed up aircraft look likely to be utilised in Denver. United is adding 32 daily flights at that hub in June (a 7.6% increase) in response to demand growth that may be the result of Southwest’s recent arrival there. Although United is likely to continue to rationalise capacity in other domestic markets, the Denver move represents a departure from the Chapter 11 strategy of reallocating aircraft to international routes.

United was the first of the US major carriers to start growing internationally to escape intensified LCC competition at home. The process began in October 2004, when the airline cut domestic flight capacity by 12% and increased international capacity by 14%. While in Chapter 11, the share of international flying increased from one–third to almost one–half of United’s total operations.

However, none of the international route areas are yet profitable; The Pacific, Atlantic and Latin America divisions lost $101m, $50m and $69m, respectively, in 2005 (loss margins of 3%, 2% and 15%).

Much of the activity has focused on the Pacific, where capacity has grown by 15% since October 2004 with the launch of San Francisco to Ho Chi Minh City and Nagoya flights, Chicago- Shanghai, Nagoya–Taipei and added frequencies to Australia and Hong Kong. This month United also returned to the San Francisco–Seoul market.

United has stated that it plans to continue in particular Pacific expansion, but most of the near term international growth looks likely to be through the Star alliance. Challenges on the international front include fleet investment and modernisation, capacity constraints at Chicago and intense competition among US airlines for new route authority to key markets such as China. If all goes well, at some point United is expected to place new orders for long–range aircraft such as the 787 or the A350. It has adequate liquidity, with estimated unrestricted cash reserves of well over $3bn at the end of March. However, the balance sheet is highly leveraged, so the company is expected to try to raise equity in an offering at the earliest opportunity.

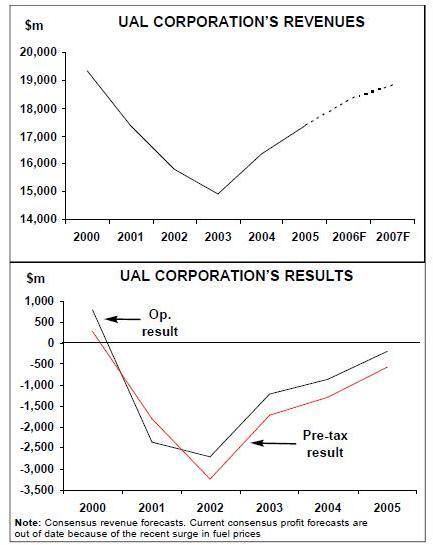

UAL has steadily narrowed its losses since 2002, when restructuring and other special items are excluded. Its results are now in line with those of other solvent legacy carriers. The current consensus estimate — which may turn out to be wildly inaccurate because of fuel — is a modest profit of $2 per share in 2006 before special items, compared to a loss of $4.88 per share last year. On the negative side, crude oil prices have suddenly surged to over $70 a barrel this month; on the positive side, US airline revenue trends are much better than anticipated because of a series of fare increases.

The critical time for United will be in a couple of years, when it should earn reasonable profits in order to meet its significant debt and lease obligations and fleet investment needs.

The reorganisation plan anticipates 10% operating margins, but that assumes the price oil falling to $50. Longer–term challenges include potential for labour disputes (if financial recovery does not proceed as anticipated) and new LCC competition, such as from Virgin America in the West.

| Type | Number | Average age |

| A319-100 | 55 | 6 |

| A320-200 | 97 | 7 |

| 737-300 | 64 | 17 |

| 737-500 | 30 | 14 |

| 747-400 | 30 | 10 |

| 757-200 | 97 | 14 |

| 767-300 | 35 | 11 |

| 777-200 | 52 | 7 |

| Total | 460 | 11 |