Southwest: prospering in any environment

April 2005

In periods of turmoil in the US airline industry, equity investors have always had one safe option (other than pulling their money out of the sector): Southwest Airlines.

The Dallas–based low–fare pioneer, now the largest US carrier in terms of domestic passengers uplifted, has proved that it can prosper in any kind of environment, thanks to its unique business formula.

Southwest has remained profitable through the post–September 2001 industry slump, albeit at reduced margins. Like other LCCs, it has made significant market share gains in the past three years.

However, its financial performance has been particularly impressive in the past 12 months or so — a period that has seen crude oil prices surge from the mid–30s to the mid–50s (dollars per barrel).

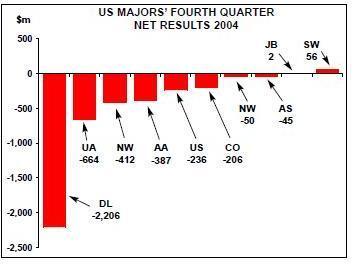

Southwest was the only US airline outside the regional sector to make a profit in the fourth quarter of 2004 — a distinction it probably repeated in the first quarter (the reporting round will begin in mid–April).

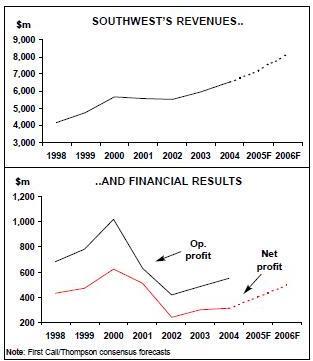

In 2004, which was Southwest’s 32nd consecutive profitable year, the airline earned highly respectable operating and net margins of 8.5% and 4.8% respectively. The results were all the more impressive in light of the fact that by the fourth quarter Southwest has accelerated ASM growth back to its customary 10% annual rate.

The latest profits are, of course, attributable to Southwest’s industry–leading fuel hedging position. In the fourth quarter, the airline had 80% of its fuel needs hedged at $24 per barrel, resulting in a $174m saving in fuel costs. Without those hedges, it would have reported losses for the fourth quarter.

Some people have inevitably drawn the conclusion that not even the Southwest business model is robust enough to produce profits at $50–plus oil prices. However, Merrill Lynch analyst Michael Linenberg recently made the point that, had Southwest not had the hedge protections, its business plan would probably have been very different.

In other words, it would probably have grown at a much slower rate than 10% in order to have some leverage to raise fares.

Southwest has the fantastic fuel hedges in place partly due to a mixture of luck and incredible foresight and partly because, unlike most other US airlines, it could afford them. The hedges have been a big feather in the hat of Gary Kelly, who put them in place as CFO. Last summer Kelly became CEO after Jim Parker’s retirement.

While Southwest has continued to outperform the industry on the revenue side, its yields and unit revenues took a rare dip in the fourth quarter, reflecting a glut of seats and intense competition in key East Coast markets. However, the airline managed to reduce its ex–fuel unit costs by as much as 4.5% through productivity improvements. A total CASM of 7.77 cents per ASM in 2004 — up from 2003’s 7.54 cents but similar to 2000’s 7.73 cents — is no mean feat in the current fuel cost environment.

Investor interest in Southwest has again intensified in recent weeks as the oil price outlook has worsened.

In mid–March Linenberg, when increasing his 2005 industry loss forecast to $5bn (based on an oil price assumption of $51 per barrel, up from $45 previously), reiterated his "buy" recommendation on Southwest due to its highly advantageous cost position.

Linenberg argued that if oil prices remain above $50, there would undoubtedly be capacity cutbacks, bankruptcies and/or liquidations, and that Southwest is well positioned to take advantage of any opportunities that could arise as a result.

Linenberg also thought that now would be an attractive point of entry based on valuation.

Southwest’s share price has been "treading water", though materially outperforming its peers, in the past 12 months.

In recent weeks the shares have traded in the $14–14.50 range, at 18 times estimated2006 earnings. Linenberg predicts that the price will rise to $19 within 12 months, representing a P/E multiple of 24. Although that would be at the high end of the company’s historical trading range (15–25), "Southwest’s relative position vis–a-vis competitors has never been this strong".

As Southwest starts playing a greater role in the industry consolidation process, and with a more aggressive CEO at the helm, investors will be keeping an eye essentially on two things. First, how far is Southwest prepared to risk moving away from its traditional business formula?

Second, will the airline strike the right balance between growth and financial returns?

In the past 12 months, Southwest has already made two somewhat uncharacteristic moves. In May 2004 it entered and began aggressively expanding at US Airways' key Philadelphia hub — a departure from its usual strategy of flying to cheaper and less congested secondary, non–hub airports.

In December Southwest signed a complex asset acquisition/investment/code–share pact with bankrupt ATAAirlines — a departure for a company that previously shunned code–sharing. Next month (May) Southwest will launch an assault on US Airways' Pittsburgh hub. Do these moves provide any pointers of Southwest’s future direction?

Costs under control

Southwest remains well protected on the fuel price front for many years ahead.

After adding to its already strong hedging position in the fourth quarter, the airline has now covered 85% of this year’s fuel needs at $26 per barrel and 65% of next year’s needs at $32.

It has also hedged 45% of 2007 needs at $31, 30% of 2008 needs at $33 and over 25% of 2009 needs at $35%.

All of that is in stark contrast with the extremely light hedging positions of most other US airlines. Compared to Southwest’s 85% coverage for 2005, Alaska and America West have the next–best coverage at 45- 50% and AirTran and JetBlue 20%-plus.

Most of the legacy carriers have currently only single–digit or no fuel hedging coverage at all.

Southwest also appears to be coping well with non–fuel cost pressures, which have built up particularly in the wage expenses category. The airline’s goal is to actually reduce non–fuel CASM in 2005, which it hopes to accomplish mainly through labour productivity improvements.

There are no open labour contracts until the pilots' agreement becomes amendable in September 2006.

Recent initiatives aimed at offsetting cost increases have included a voluntary early retirement programme and consolidation of reservations centres. While it is tough for such a lean and efficient company to continue reducing unit costs, the top executives said recently that there were more ideas than could be implemented.

As a result, Southwest’s profit outlook is pretty good. The current consensus forecast is that its earnings per share will rise from last year’s 41 cents to 50 cents this year and 61 cents in 2006. The net profit margin is expected to improve steadily, to around 6%by 2006.

CFO Laura Wright indicated recently that the company is aiming to return to its "long–term average net margin of 7.5- 8%". In the boom years of the late 1990s, Southwest was achieving 9–11% net margins.

Significantly, Southwest has maintained investment grade credit ratings through the industry crisis. Its balance sheet is stronger than ever, with total assets of $11.3m, shareholders' equity of $5.5bn and long-term debt of $1.7bn at the end of 2004.

The lease adjusted debt-to-capital ratio has remained in the low 40% range for many years (100%- plus is now typical for the other large majors).

Although the year-end cash balance of $1.3bn was down from $1.9bn three months earlier and below the management's goal of $1.5bn (largely because of the ATA transaction), at 20% of 2004 revenues, it was still extremely healthy by industry standards.

Furthermore, Southwest has a $575m unused credit facility. It also has more than $6bn of unencumbered aircraft, most of which are Section 11 eligible and would therefore make attractive collateral in financings.

As a result, Southwest enjoys significant financial flexibility, including easy access to the capital markets. It was able to tap the unsecured debt market in February, raising $300m in 12-year notes with an interest rate of only 5.13%.

A third of the proceeds were used to refinance more expensive debt - some with interest rates as high as 8% - while the rest added to the liquidity cushion.

Fitch Ratings noted in a recent report that, despite the return to the customary 10% ASM growth, Southwest retains the flexibility to meet heavy capital commitments almost entirely from operating cash flow.

Current plans envisage total capital spending of around $1.4bn annually over the next 2-3 years. This year's scheduled debt maturities are only $146m, though the figure will rise to $605m in 2006.

Southwest is therefore uniquely well positioned to meet not just its substantial aircraft capital spending requirements but whatever investment opportunities may arise from industry restructuring.

The ATA transaction: rationale and implications

The ATA transaction, secured through bankruptcy auction in December in a hot contest with AirTran, involved Southwest purchasing six of ATA’s 14 gates and a maintenance hangar at Midway, Chicago’s secondary airport, for $40m. Southwest also provided $47m of debtor–in–possession (DIP) financing, which will be converted to a term loan when ATA emerges from Chapter 11. Southwest agreed to buy $30m of equity in the reorganised company, representing a 27.5% stake. The fourth component of the deal was code–sharing at Midway and other points.

Southwest has made it very clear that it only wanted the Midway facilities and that the other components were there because they were necessary to clinch the deal.

Therefore there is nothing strategic about the ATA investment or the code–shares. The $117m deal represented a relatively small capital investment for Southwest.

Also, the airline is probably not taking much risk with the DIP financing, because the loan is believed to be collateralised on ATA’s eight remaining Midway gates. In the event that the equity stake is acquired (it would be nonvoting), Southwest is expected to liquidate it in an orderly manner over time.

That said, the revenue benefits anticipated from the code–share alliance, which Southwest and ATA began implementing in early February, are not insignificant — $25- 50m annually for each airline. "For a modest investment on our part, we have the potential to add quite a bit of revenue", Kelly observed recently, calling the return on investment "astronomical". He also said that he had always felt that there would be such a scenario for adding incremental revenue. In other words, Southwest now seems open to the idea of limited code–sharing, as long as a deal augments its service and meets its strict criteria on financial return. However, Kelly has stressed that the strategic focus will not change — Southwest will remain a point–to–point nonstop airline, with connecting traffic accounting for only a fraction of its business.

In the past LCCs have avoided code–shares partly for fear of harming their image and service standards or confusing passengers. The ATA–Southwest deal will obviously be helped by the fact that ATA too has a good reputation for customer service and on–time performance. Unlike Southwest, it offers a business class (the code–shares will only cover ATA’s coach class).

Another reason LCCs have avoided code–shares is that harmonising booking systems and technology is costly. It takes an effort to do things that are outside the basic simple LCC model. But Kelly made the interesting point that technological advances have eased the problem.

He said that he did not think Southwest would have been technologically capable of implementing the ATA code–shares five years ago — now it is just more flexible in that respect. Southwest executives have also said that the ATA transaction is manageable because ATA is only about one tenth of the size of Southwest.

The code–shares are expected to add less than 1% to Southwest’s connecting passengers.

The code–share agreement is initially for one year, but it will automatically be converted into an eight–year term once ATA’s reorganisation plan is confirmed. The first phase, linking 11 ATA cities with 40–plus Southwest cities via Chicago Midway but not involving FFP cooperation, was due to be fully implemented by early April. On April 3 ATA’s Phoenix–Hawaii service was added to the agreement, and more routes are likely to follow in the coming months.

The ATA code–shares are giving Southwest an opportunity to tap into essentially two new types of markets: major hub airports (including New York LaGuardia, Washington Reagan National and Boston Logan) and international leisure destinations such as Hawaii and the Mexican beach resorts.

Southwest has not publicly commented on this, but the opportunity to sell tickets to Hawaii is probably especially valued, given that it is a major gap in its nationwide network (Southwest does not have the long–range aircraft).

ATA has sizeable Hawaii operations from five mainland cities, adding up to 62 weekly flights this summer. But the code–share benefits pale into insignificance when compared to the benefits of getting the extra gates at Midway.

Before the ATA transaction, Southwest was already the second largest airline at the airport, with 145 daily departures and a 40% traffic share. It now holds 25 gates or 58% of the airport’s total 43 gates, giving it the potential to build Midway into an operation rivaling its 26–gate Baltimore operation. Southwest has said that it sees Midway as the largest potential market in its route system.

Kelly called it "one of the best expansion opportunities we have had in perhaps a decade or more".

Southwest wanted the extra gates quickly because, like Chicago O'Hare, Midway is gate–constrained, with no near–term facility expansion opportunities. It has a strong local market and, because of the capacity constraints, promising unit revenue growth fundamentals.

The move ensured that no other LCC would be able to establish an early significant presence at Midway. With Southwest and ATA between them controlling about80% of the Midway gates, the main competitive impact will be on the O'Hare legacy carriers — United and American, which operate major hubs at O'Hare, and US Airways, which has significant nonstop service out of the airport.

Since acquiring the extra gates, Southwest has moved quickly to expand service. Last month it announced the addition of seven new destinations from Midway and frequency increases on existing routes from the early summer. As a result, the airline’s daily departures from Midway will increase by 32%, from the pre–ATA 145 to 192.

The ATA transaction and Southwest’s Midway strategy offer some pointers of things to come further down the industry consolidation road, for example with US Airways. First of all, Southwest is mainly interested in asset buyouts, not mergers or acquisitions. This is in line with the general industry thinking, reflecting the disappointing results of most large airline mergers in the past, as well as a current lack of investment funds or goodwill on the part of employees, though Southwest’s strong corporate culture obviously gives it special incentive to avoid mergers.

Second, and a little more surprisingly, Southwest showed with the ATA transaction that, when a good opportunity arises, it is prepared to go to great lengths to get the assets that it wants, even if it means entering into highly complex transactions. It is going to embrace change and keep adapting to a changing environment, rather than religiously sticking to its basic business model.

East Coast expansion focus

In addition to Chicago, Southwest’s expansion this year focuses on two East Coast cities: Philadelphia and Pittsburgh.

Philadelphia, added in May last year, was Southwest’s first new city since late 2001. The airline has described it as "our most aggressive route start–up ever", having quickly built up the operation to 41 daily flights to 16 destinations within six months of start–up.

Philadelphia was a classic overpriced and under–served market, a US Airways stronghold with only 5–10% of traffic carried by discount airlines. There was a rare opportunity to obtain gates after AMR’s purchase of TWA. While US Airways' shrinkage played a major part in Southwest’s Philadelphia decision, competitively the move was probably more aimed at JetBlue and AirTran — namely preventing other LCCs from establishing a presence at that airport.

The operation has been a huge success, with the famous "Southwest effect" very much in evidence. The airline plans to continue adding flights at Philadelphia.

The only problem is that it currently has only six gates, limiting daily departures to around 60.

Southwest has said that it would one day like to have up to 25 gates at Philadelphia.

The immediate focus, however, is on Pittsburgh, which Southwest is adding in early May. The initial operation will be in the typical Southwest pattern — ten daily departures to four destinations, a mix of short and long haul, with walk–up fares in the $79-$299 range, representing savings of up to 65% on prevailing fares.

The move represents another assault on US Airways, which is still the dominant carrier at Pittsburgh. However, this time US Airways was really asking for it because of its heavy downsizing at that airport.

After gradually cutting service in Pittsburgh in recent years, in 2004 US Airways decided to abandon it as a hub but maintain sizeable operations (still some 220–plus daily departures).

This created a perfect opportunity for Southwest (even though other LCCs had already moved in) — similar to its earlier opportunity at Nashville, after American downsized at that airport.

In recent months Southwest has talked about possibly adding another new city in late 2005. Given all the turmoil in the industry, it expects to wait until the last minute before deciding about it. Not surprisingly, there has been some speculation about Charlotte (North Carolina) — another US Airways hub.

It has been at least a decade since Southwest added a new city in the West, and the airline’s executives acknowledged recently that there are candidates west of the Mississippi. However, for now the focus appears to be totally on the East.

After a decade of growth in the East, Southwest has now a more geographically balanced domestic network. In the fourth quarter of 2004, its capacity was distributed as follows: West 39%, Midwest 16%, Southwest 16%, Southeast 15% and Northeast 14%.

Alongside with its low fares and strong nationwide network and brand image, one of Southwest’s biggest advantages is its extremely strong competitive position in the markets that it serves. According to 3Q04 DoT data, Southwest is the largest carrier in 90 of its top 100 O&D markets. It has a 66% share of traffic in its top 100 O&D markets, with dominant shares in the intra–California, intra–Florida and intra–Texas markets. It also has a strong presence in the Northeast- Florida market and at Chicago Midway, Baltimore, Phoenix and Las Vegas.

However, this year’s new pricing developments (Delta’s SimpliFares) may prompt Southwest to re–examine some of its strategies.

First, relying on secondary airports may make less sense if fares decline at primary airports (though Southwest has pointed out that secondary airports do have advantages — for example, they are easier to get to and have less congestion). Second, the traditional strategy of going for overpriced and under–served markets may have to be revised, because the legacy carriers' fare cuts may have eliminated many overpriced markets.

But Southwest has indicated that none of that is really new — that it was already mindful of the fact that, as time goes by, it will face more and more low–fare competition. In other words, it will have to adjust its strategies over time anyway.

One area that Southwest has certainly re–examined is product and service quality.

In February it unveiled refurbished aircraft interiors, featuring leather seats and more personal space. It also continues to keep assigned seating under consideration — apparently a perennial request by some of its customers. However, Southwest does not follow every trend or fad, and often for a good reason. Kelly observed recently that business customers typically like Southwest because of its schedule, frequencies, punctuality and suchlike, so the airline needs to focus on what is most important, including price.

Could Southwest grow faster?

Southwest’s current fleet plan calls for the net addition of 29 aircraft in 2005 — the result of 34 new Boeing 737–700 deliveries and the retirement of the last five 737–200s.

This will meet the airline’s current capacity needs for Midway, Pittsburgh and Philadelphia, plus possible service from a new city in late 2005. It will result in ASM growth of around 10%, following 7.1% last year, 4.2% in 2003 and 5.5% in 2002.

If good additional growth opportunities cropped up, Southwest could in theory take half a dozen or so more aircraft per year.

It is keeping an eye on the used aircraft market. However, Southwest executives say that in the current environment it would be hard to reach that decision.

Kelly estimated in January that in the current environment the right level of growth for Southwest is probably in the 5–10% range. If the excess capacity situation eases and profit margins improve, it would be easier to justify a 10% growth rate. Then again, Southwest is well protected on the energy side and may be able to reach its financial return targets even while growing faster.

| Order | |||

| Type | Active | Backlog | Options |

| 737-300 | 192 | ||

| 737-500 | 25 | ||

| 737-700 | 203 | 80 | 86 |

| Total | 420 | 80 | 86 |