Airline finances: a tale of two halves

April 2005

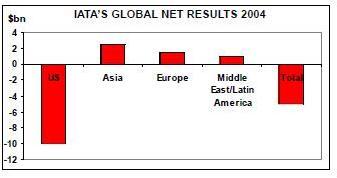

The past few years have seen airline financial performance diverge significantly in different world regions. IATA’s chief economist Brian Pierce, speaking at a recent UBS transportation structured debt conference in New York, called it a tale of two halves — the US legacy carriers' performance being pretty disastrous and the rest of the world faring much better. According to IATA, US airlines lost about $10bn in 2004, while airlines in other regions saw small profits ($2.5bn in Asia, $1.5bn in Europe and $1bn in the Middle East and Latin America).

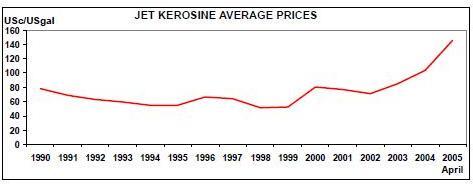

It is not just differences in the rate of financial recovery after September 11. Oddly enough, the trends seem to have moved in opposite directions as fuel prices have surged in the past 12 months. While US legacy carriers have incurred deeper losses, European operators have moved into profit and some Asian airlines are now turning in excellent performance.

While differences in the competitive and revenue environments obviously account for much of the variation in the level of earnings, Pierce noted two other significant factors at play in recent months: depreciation in the value of the US dollar and the extent of fuel hedging.

Since oil is priced in US dollars, the falling dollar has offered particularly European airlines partial protection against rising fuel prices. Pierce was brave enough to predict that, given the scale of the US current account deficit (and despite rising interest rates), the dollar was likely to continue to weaken. Of course, this is also increasing the finance costs of the heavily indebted US legacy airlines.

Airlines outside the US also currently tend to have better fuel hedges in place, giving them greater shelter from rising oil prices.

Last year roughly 40% of the global airline industry fuel bill was hedged, though Pierce estimated that for 2005 the percentage is only 20%. He noted that the percentage is considerably less in the US and therefore the US and non–US financial trends are likely to continue to diverge this year.

With the notable exception of Southwest (see briefing, pages 6–11), which has hedged an impressive 85% of its 2005 fuel needs at $26 WTI per barrel, the large US airlines have single–digit or no hedging coverage at all this year.

Some of the US–Asia variation in airline financial performance reflects significant differences in unit labour costs. This is partly structural — US legacy carriers are much more dependent on their shorter–haul domestic markets than large airlines elsewhere — and partly due to absolute differences in labour rates.

According to IATA, Asian carriers' labour costs are 3–7 cents per ATK or 18% of operating costs, compared to US carriers' 16–18 cents per ATK or 38% of operating costs.

As regards the differences in the revenue environments, Pierce noted that large European airlines are able to collect significantly higher revenue premiums over LCCs than US legacy carriers are. This mainly reflects differences in the route mix, with the large European (as well as Asian) airlines having a larger proportion of longer–haul international routes. Yields in such markets are more robust, because there is less competition from LCCs and because passengers tend to be more willing to pay revenue premiums on longer journeys.

IATA’s analyses suggest that LCCs are now present in just as many short–haul markets in Europe as in the US domestic market. Yields in both of those markets have fallen by 30% in real terms since 1992.

However, competition is much fiercer in the US because LCCs there compete with the legacy carriers directly at hubs, rather than indirectly at secondary airports as in Europe. In effect, in Europe the decline in short–haul yields has been moderated by airport capacity constraints.

Large European airlines have higher cost levels than the US legacy carriers. However, due to structural differences, they enjoy much higher yields, which have protected their profitability.

The past month has actually seen modestly positive revenue trends in the US domestic market, thanks to four subsequent fare increases led by the legacy carriers. UBS analyst Robert Ashcroft suggested that the increases have "come close to compensating for oil". However, the fare levels remain extremely low, and profitability will be elusive unless excess capacity is eliminated.

While trends in the European short haul markets offer no reason to celebrate either, there are reports of a distinct recovery in corporate travel demand in longer–haul markets. According to UBS analyst Damien Horth, BA has reported 10% premium traffic growth in long–haul markets in the past few months. However, he noted that because of the sharp decline seen in 2000–2003, when a key market like the North Atlantic lost 30% of its "GDP share" (another measure of the health of the industry), there is still a long way to go.

IATA is forecasting a tougher year globally in 2005 because of a higher average price of oil and a lower overall level of hedging. The aggregate industry loss is expected to be larger than last year’s $4.8bn.