Virgin Express: a disappointing LCC

April 2004

If the proposed Virgin Express/SN Brussels deal goes ahead — and it’s by no means certain that it will — will Sir Richard Branson be accepting defeat in his attempt to set up a LCC in Europe, at least in the guise of Virgin Express at Brussels National airport? VE started life in 1992 as EuroBelgian Airlines, before being bought by the Virgin empire in 1996 and relaunching as a low fare airline. Currently VE operates to 16 European destinations with six 737–300s and six 737–400s, though VE once had much greater ambitions. Indeed the current fleet will soon fall to 11 after VE returns another 737–400 to a lessor after its lease expires. This will be the second aircraft to be returned to lessors this year, and with no new aircraft scheduled to replace them, VE is gradually reducing capacity, even before a deal with SN is finalised. The fleet has steadily been cut back from 22 aircraft since David Hoare became executive chairman of VE in 1999.

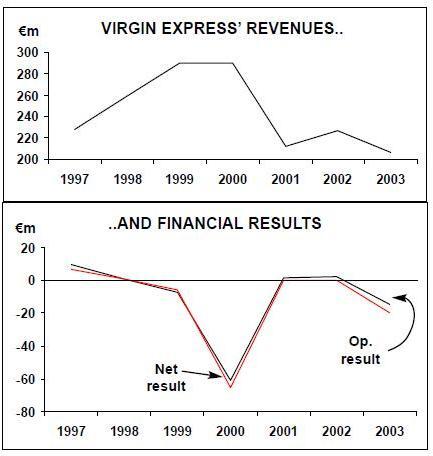

At the end of March, VE announced its financial results for 2003. For the calendar year, VE reported a 9% reduction in revenue to €207m, an operating loss of €14.8m (compared with a €2.6m operating profit in 2002) and a net loss of €19.6m (compared with a €0.4m net profit in 2002).

Yields fell by 21% over the year, and VE’s net loss works out at €8 per passenger flown. David Hoare attributes the poor results to the Gulf War, price discounting by Europe’s scheduled airlines, and Ryanair’s “illegal subsidies” (see below).

To make matters worse, VE also announced that as a result of an audit carried out before detailed merger talks with SN begin, errors in an IT system and their control led to “historically uncollectable debts” which will mean adjustments to the P&L accounts for 1999, 2000 and 2001 equivalent to a 1% reduction in revenue over those years (and which is not reflected in the VE revenue graph, see right).

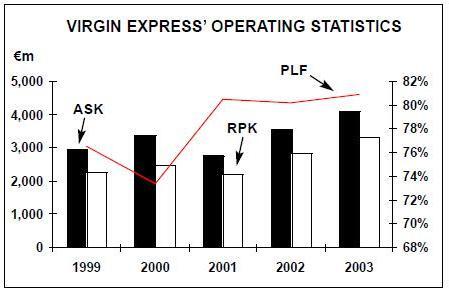

VE carried 2.5m passengers in 2003, 5.2% up on 2002, and load factor was 81%, compared with 80.7% in 2002, but the unit revenue figure was dire. Revenue per ASK fell by 21% in 2003, far outstripping an 11% reduction in cost per ASK (which was partly helped by the strengthening of the Euro against the dollar). The cost cutting has included the trimming of staff (the workforce is now less than 1,000 strong), a reduction in leasing costs and the renegotiation of handling contracts at non–Belgian airports.

Aircraft utilisation has also increased, to an average of more than 12 hours per day per aircraft. For example, after the collapse of a code–share between VE and SN in March 2003, VE utilised spare capacity by linking with Dutch travel company Airtrade to launch an Amsterdam–Rome route (on which Airtrade agreed to buy half of all available seats.)

Cost per ASK in 2003 was 5.44 Eurocents, but Hoare added: “Given our low cost position we are surprised to find large network operators pricing below our costs, particularly in the case of Alitalia on flights to Milan and Rome. We will be interested to hear the EC’s view of this airline’s activities.”

This emphasis on cost–cutting is partly the result of VE facing competition from Ryanair, which has a hub at Charleroi, 50km to the south of Brussels Zaventem airport.

Ryanair operates out of its Brussels Charleroi hub to 10 destinations — Glasgow Prestwick, Dublin, Shannon, Carcassonne, Valladolid, Barcelona Girona, Rome Ciampino, Pisa, Venice Treviso, Milan Orio al Serio and Stockholm Skavsta — and its presence irked VE so much that in October 2003 (following the release of its third quarter results where revenue dropped 8%) VE complained to the EC about airport sweetener deals. Specifically, VE called for the EC to force Brussels Charleroi airport to stop providing subsidies to Ryanair, a practice it claimed was anti–competitive.

In February 2004 the EC did exactly that, forcing Ryanair to hand back subsidies to the airport. Ryanair responded by shutting its London Stansted–Brussels Charleroi route and threatening to drop other services, subject to ongoing talks with the airport.

Though the Charleroi/Ryanair deal probably did affect VE, its outrage about Ryanair must be taken with a degree of scepticism, particularly given a January 2003 report by the Belgian parliament that criticised deals made by the then Sabena CEO Paul Reutlinger with VE.

VE flew three routes for Sabena (Brussels to Heathrow, Rome and Barcelona) and the Belgian flag carrier guaranteed to pay for a certain amount of seats per flight, whether or not they were filled.

The report contained claims by Christophe Müller, Reutlinger’s successor, that the block space deals cost up to €30m a year, and that without these payments VE may not have survived. The report also criticised a 1997 deal in which Reutlinger sold Sabena slots at Heathrow to Virgin Atlantic for $8m.

Certainly without the Sabena block space deal, VE’s results would be even worse than they were and would have made the airline’s quest to expand away from Brussels even more urgent than it already was. VE was twice frustrated by failed attempts to launch low–cost operations elsewhere, at Cologne in October 2002 and Paris Orly in 2003.

The Cologne–Bonn plan collapsed once VE saw impending competition from LCCs, specifically Hapag–Lloyd Express (part of the TUI empire) and Germanwings (in which Lufthansa has a stake), which both revealed plans to offer low cost operations at the airport.

If VE had gone ahead, it would have stationed up to 20 new aircraft at Cologne.

At Paris Orly, after the collapse of Air Lib (the merged Air Liberte and AOM) in February 2003, VE was awarded enough slots to start services to Bordeaux, Toulon and Rome Fiumicino (though just a fifth of the slots it applied for), but it decided not to start services after claiming that slot timings were not close enough to allow the aircraft utilisation it wanted. VE said: “Only one of these three routes had the potential for profitable operations in the near future.” If VE had obtained the slots it wanted, again the airline would have based a substantial fleet at Orly. Initially, VE had even considered buying the assets of Air Lib and setting up a French carrier, in co–operation with French shipping company CMA CGM, but this plan was soon scaled back in favour of slot acquisition.

It’s more than likely that VE has considered many more airports than Cologne and Paris Orly, but no second base has materialised and VE has been stuck with its Brussels National base in the face of increasing competition and capacity, and an inevitable reduction in yield.

And according to David Hoare, “airport charges at Zaventem continue to be uncompetitive when compared to airports serving markets of similar size, and these high costs place Belgian airlines operating from there at a serious disadvantage”.

Strategically, VE is at a dead end, and Branson may consider the proposed SN/VE deal as something of a late but lucky escape. An IPO in 1999 saw Virgin selling 49% of VE, but Virgin’s share leapt to 88.6% in July 2004 following a €35m rights issue that was taken up by the Virgin holding company.

The money was used to repay loans owed to another Virgin company, Barfair, but at the same time the Virgin group also gave VE a new working capital facility of up to €50m. In many ways the cash that Branson invested in VE is irrelevant — what matters more is that his attempt at a low cost European airline has foundered while easyJet and Ryanair have rampaged across Europe.

Presuming that the SN/VE deal is signed, how will this fit into Branson’s plans? BMI British Midland still doesn’t appear keen to merge with Virgin Atlantic, and if BMI doesn’t change its mind then Branson may have to build a European operation on his own. And that’s the value of the SN/VE deal.

On 1st January 2005 Virgin can exercise its put option and Branson would be free to launch another low cost operation, this time well away from the nightmare of Brussels. It is inconceivable that the final SN/VE deal will contain clauses forbidding Branson to use the Virgin name elsewhere in Europe once the put/call options are exercised.