AirTran:the business model for the Majors?

April 2003

AirTran Airways, the largest of the early 1990s crop of new entrants, is now as profitable as Southwest or JetBlue, despite operating with a distinctly different business model. It is the type of model that the US Majors might aspire to.

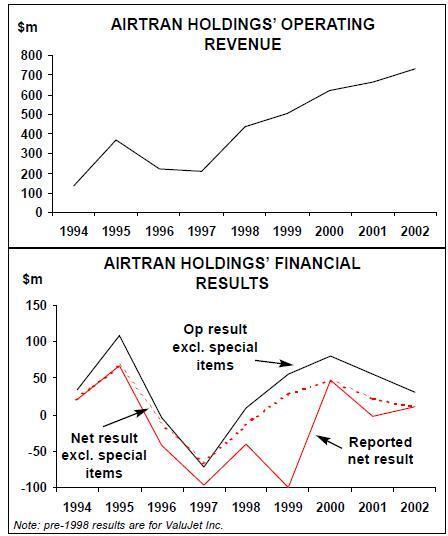

AirTran posted net profits before special items for both 2001 and 2002 — a rare feat in the US airline industry. The 7.2% operating margin that it achieved in the fourth quarter was the industry’s second highest after JetBlue’s 16.8% (Southwest’s was 6.3%).

The profits were impressive also in light of AirTran’s stepped up ASM growth (7% in 2000, 12% in 2001 and 26% in 2002). After September 11 the airline accelerated its Boeing 717 deliveries, in part to obtain more timely cost savings from fleet renewal. It accepted 43 new aircraft in 2001–2002 — more than any other US airline. This meant that it was quickly able to take advantage of US Airways' downsizing, while continuing to successfully fend off Delta at their shared Atlanta hub.

While Southwest and JetBlue have been present in coast–to–coast long haul markets for some time, AirTran is only venturing from its Eastern US stronghold to the West Coast this summer. Given that the major carriers' biggest cuts are likely to be in the East, why is the low–fare airline now going west?

AirTran will also be in the news because it has to be the only US airline looking to place a large new aircraft order this summer. It needs a longer–range aircraft type and is considering proposals from both Boeing and Airbus.

AirTran’s business model is interesting because it has components of the sort of strategy that the major carriers should try to aim for. The airline offers a separate "affordable" business class (rather than single–class like Southwest and JetBlue) and its unit costs are in the 8–9 cent range (rather than 6–7 cents). It is primarily a hub–and- spoke carrier but has always operated its main Atlanta hub using the more efficient free–flow system that American and others are now interested in.

On the negative side, AirTran’s financial profile is much weaker than Southwest’s and JetBlue’s. While analysts remain bullish about its longer–term prospects, its highly leveraged balance sheet (when operating leases are included) and lack of a credit line pose risk in the current industry environment. It may avoid a liquidity crunch, but will it be able to execute its growth plans?

AirTran is fortunate in that it was in great shape when the industry crisis began. When it was last featured in an Aviation Strategy briefing in March 2001, it had just staged an impressive financial turnaround in 1999–2000, after three years of heavy losses as it rebuilt operations and restructured itself after predecessor ValuJet’s 1996 crash and three–month grounding.

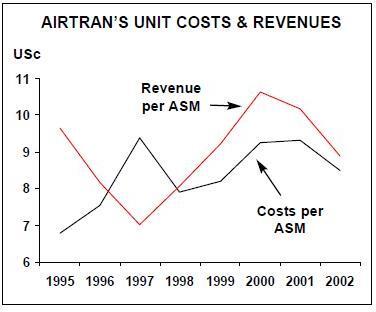

The company had retained a low cost culture despite becoming a more up–market and conventional type of operation. It had also raised its unit revenues from just 7 cents per ASM in 1997 to 10.65 cents in 2000, largely thanks to success in attracting business traffic. It had introduced the 717 to its fleet in October 1999 and obtained lease financing on highly favourable terms for deliveries up to February 2002. Most importantly, it had persuaded Boeing Capital to refinance $230m of debt that was due in April 2001.

With all of those issues resolved, AirTran was ready to focus its efforts on growth, fleet renewal and consolidating profitability. As things turned out, it accelerated growth and fleet renewal, made extra efforts to cut costs and boost liquidity and escaped with only two quarters of marginal losses.

Substantial cost advantage

AirTran has achieved impressive cost cuts over the past 18 months; in 2002 its unit costs fell by 8.8% to 8.51 cents per ASM.

It appears to enjoy a substantial cost advantage over its main competitors — by its own estimates, at its average stage length of 575 miles, Delta and US Airways have 35% and 50% higher unit costs respectively.

AirTran executives suggested recently that even after US Airways' restructuring the cost advantage would still be 40–45%.

Significantly, AirTran was able to achieve meaningful cost reductions in the wake of September 11 without furloughing workers. Thanks to great labour relations, it quickly secured agreements with its pilots and other key groups on a range of temporary measures, including salary cuts and more flexible work rules, that reduced payroll costs by about 20% — the same as the initial capacity reduction.

As well as helping maintain morale, this strategy ensured that the airline had all the people in place to quickly respond to new market opportunities.

At a recent conference, AirTran’s CEO Joe Leonard described current staff morale as "absolutely sky–high". This is because the company is growing "whereas the competitors who used to mock our employees are getting laid off" (a reference to Delta). Labour agreements are in place with all groups until late 2004–2006, except for the flight attendants whose contract became amendable in October 2002 and who are currently in negotiations.

The fleet renewal process has contributed substantial cost savings, particularly in fuel and maintenance. The 717’s 24% better fuel burn over the DC–9 resulted in an $11.8m cost saving in 2002. The earlier decision to accelerate 717 deliveries has obviously paid off handsomely in light of the sharp pre–war surge in fuel prices.

Like other airlines, AirTran has continued to benefit from lower distribution costs.

Internet sales have risen to account for 56% of total sales in 2002 — among the highest percentages in the industry. The carrier estimates that the cost of booking a passenger on the Internet is just 20 cents, compared to $5.50 via a travel agency (or $3 via AirTran’s own internal reservation system).

Relatively weak balance sheet

AirTran fortunately managed to repair its balance sheet from the worst damage inflicted by the post–ValuJet restructuring before the post- September 11 crisis hit the industry. Cash position improved from just $10.8m at the end of 1998 to $103.8m at year–end 2000, while stockholders' equity recovered to $7.9m positive from a deficit of $40m in 1999. The April 2001 refinancing replaced a $230m balloon payment due that month with $201.4m of new debt obligations due in 2008–2009.

The balance sheet has continued to gradually strengthen thanks to continued profitability. Cash reserves amounted to $150m in early March, up from $138.3m at the end of 2002 and $130m a year earlier. Stockholders' equity rose from $33.4m at year–end 2001 to $51.9m at year–end 2002, while long–term debt (including current portion) fell from $254.8m to $199.7m in the same period.

However, AirTran’s debt–to–total–capital ratio (including operating leases) is currently about 93% — similar to the large network carriers' ratios and in an entirely different league from Southwest’s low 40s or JetBlue’s 60s. The ratio is expected to decline marginally by 1–2 points in 2003.

AirTran relies on internally generated cash to meet liquidity needs, because it has no short–term credit facilities and substantially all of its assets are encumbered. On the positive side, however, it has very modest debt maturities — just $10–18m annually in 2003–2007 — and low capital spending needs because all of the 717s will be leased from Boeing Capital. Contractual obligations and commitments add up to $201m in 2003, followed by about $140m annually in 2004–2007.

The bulk of it is operating lease payments, which amount to $133m in 2003 and $121–128m annually in subsequent years.

Improved business mix

While AirTran caters for all passenger segments, it has a product strategy that is more specifically designed to meet the needs of business travellers than the Southwest and JetBlue models are. It offers "key attributes of major airlines at affordable prices". This includes a simplified fare structure, walk–up fares that are generally 60% below those of high–cost competitors, a business class product for only $35 extra per segment, assigned seating and frequent–flyer and corporate travel programmes.

The airline believes that having a separate business class cabin, with larger seats and more legroom, as well as five–abreast seating in the coach cabin (rather than the normal six–abreast) are key attributes that set it apart from competitors. (The five–abreast seating means that 83% of seats must be filled before somebody is forced into the middle seat.)

These strategies have been instrumental in pulling in business traffic. Although the revenue mix has deteriorated since September 11, AirTran is seeing growth in business customers and believes that they are coming from the larger carriers. There are also growing numbers of repeat customers.

At a recent Raymond James investor conference, Leonard presented the results of a new passenger survey that showed dramatic changes in the make–up of AirTran’s clientele from four years earlier. First, 38% of its passengers now have a household income of at least $100,000 (no longer backpackers). Second, 65% of the passengers fly at least once a month and 15% fly at least once a week (extremely frequent flyers). Third, 85% of the passengers were satisfied with their most recent trip on AirTran (the highest percentage ever seen by the company that carried out the survey). Fourth, 68% of the passengers agreed or completely agreed that AirTran’s service is comparable with or better than any other airline.

Growth opportunities

AirTran has so far focused on short haul markets primarily in Eastern US, where it enjoys the greatest cost differential over competitors. The strategy is to serve large primary business centres and develop under–served secondary markets.

Two years ago the network was still heavily focused on Atlanta, which accounted for 90% of AirTran’s passenger flows, though the airline had begun to diversify with some point–to–point services from Chicago and in the Northeast–Florida market. It was keen to expand service from the Northeast and even establish a new hub operation there, but those plans were hampered by a lack of airport slots and gates.

Over the past 18 months there have been several significant developments. First, US Airways' decision to eliminate MetroJet in late 2001 provided an opportunity for AirTran to develop a hub at Baltimore–Washington — it announced its schedule within five days of US Airways' announcement. The operation, which will have grown to ten cities by June, is apparently a great success and will see further expansion. AirTran is the only jet operator from Baltimore to cities such as Boston, Fort Myers and Grand Bahama Island (its recently–introduced second international route), but it has also fared well in head–on competition with Southwest on the Orlando and Tampa routes.

Second, AirTran has passed some of its hardest- hit short haul markets in the Southeast to a new regional jet operation established with Air Wisconsin. "AirTran JetConnect" will not be a huge network (at most perhaps 10 CRJs by year end); rather, it is seen as a tactical move to discourage the major carriers from coming into those markets with longer–haul RJs.

Third, AirTran announced last month that it would begin twice–daily service from Atlanta to Los Angeles, Las Vegas and Denver in May and June, as part of a new focus on east–west expansion. The West Coast flights will initially be operated with wet–leased A320s because the 717s do not have the range (AirTran’s pilots have agreed to the arrangement as long as necessary).

Going west just as opportunities are cropping up in the East may not make sense at first glance, but JetBlue has demonstrated that the economic benefits of such a move can be significant for a north–south short haul carrier. The main benefits are improved aircraft utilisation (as the operating day is extended) and reduced seasonal variation in earnings. AirTran specifically wants to boost earnings in the third quarter, when the Florida market is weak.

These new services are part of a strategy to "selectively add" service at Atlanta — the nation’s fourth largest travel market — which has seen its share of AirTran’s passenger flows decline by 16 percentage points in the past two years to 74% at the end of 2002. The airline has a great 26–gate facility at Atlanta Hartsfield, which also happens to be one of the nation’s cheapest airports to operate from.

Interestingly, AirTran has always operated Atlanta more like a "rolling complex" than a classic hub where aircraft arrive and depart in waves.

The first and the last banks of the day are classic hub–style, but at other times the airline free–flows aircraft. This explains why it has relatively high average aircraft utilisation for a short haul carrier (about 11 hours daily). Over the past year American, in particular, has been resigning its hubs into rolling complexes.

AirTran certainly expects to continue to take advantage of new market opportunities in the East as the major airlines retrench further. It is interested in developing both point–to–point services and new focus cities like Baltimore.

The leadership is not too concerned about Delta’s Song (which is due to begin operations on April 15) or other planned low–fare units within high–cost airlines, because "we think our business model has been proven". Over the past two years, Delta has mounted a particularly aggressive competitive response to AirTran, with little adverse impact on the smaller carrier.

Fleet plans

This is a very important year for AirTran on the fleet front. First, it will be finishing the 717–200 deliveries (taking the last 23 on firm order to bring that fleet to 73 by year–end) and retiring the remaining 10 DC–9s. Second, it will need to decide on a new aircraft type — it needs a longer–range model and more aircraft (only six purchase options remain on the 717s).

Completion of the 717–200 programme means that AirTran will have transformed its fleet from one of the industry’s oldest to one of the youngest in just over four years.

The average fleet age will be less than three years at the end of 2003, compared to 27 years at the end of 1998.

The process of selecting the longer–range aircraft type began a couple of months ago, when AirTran requested proposals from both Boeing and Airbus. Preliminary talks have focused on three types: the stretched or longer–range 717- 300 (which Boeing may or may not launch this summer), the 737–700 and the A319.

(The preliminary 717–300 proposal that AirTran received would put in four extra fuel tanks to permit nonstop operation from Atlanta to Los Angeles.)

Since AirTran is talking about placing an order for 100 aircraft, it will no doubt be an extremely hot contest. The management has noted many times recently that this is an exceptionally good time to be buying aircraft and that they believe AirTran can do a better deal on new aircraft than on used aircraft. The airline says that it never intended to operate a single aircraft type — something that, in any case, is a less important consideration now that prices (and hence ownership costs) are so low.

CFO Stan Gadek indicated in January that AirTran hoped to start buying aircraft, suggesting that it might go to the debt markets in conjunction with the longer–range aircraft order. It has leased all of the 717–200s from Boeing Capital, except for the first ten that were financed with an EETC transaction in 1999.

Prospects

Up to early March AirTran was enjoying strong traffic and revenue trends and forward bookings, but the war in Iraq has meant that it is likely to only break even financially in the first quarter. However, it is still expected to post a healthy profit for 2003 — a feat that only a few US airlines will accomplish — despite 25%-plus capacity growth.

The current First Call consensus forecast is a profit of 46 cents per share in 2003, which would be more than three times the 14 cents earned last year, and a profit of 78 cents per share in 2004.

However, these estimates are likely to change when the full impact of the war becomes clearer.

In AirTran’s case, the negative effects of the war on traffic and revenues will be mitigated by its low cost structure and favourable cost trends.

Unit costs will still decline this year as the final phase of the fleet transition is completed. Also, AirTran had the foresight to take on additional fuel hedges in early February, which gave it an excellent hedge position: 70% of first–quarter needs at mostly 86 cents per gallon (maximum 97 cents) and 55% of second–quarter needs at a maximum price of 87 cents.

Until very recently, AirTran’s shares were on the "buy" or "strong buy" lists of most analysts. However, the share price has gone against market trends over the past six months and more than doubled to $6–7 from the September- October lows of less than $3. This led some analysts, including Merrill Lynch’s Michael Linenberg, to lower their recommendations to "neutral" mainly due to valuation at the end of March. However, in contrast, Raymond James analyst Jim Parker retained his "outperform" rating and raised the 12–month price target from $7 to $9.50 (the consensus median 12–month target was $7.50 at the end of last month).