KLM: under pressure from LCCs, still seeking European partner

April 2003

KLM’s high cost base, small catchment area and a reliance on transfer traffic makes an alliance with a European major a strategic imperative for the Dutch flag carrier, but — with worrying regularity — proposed partners appear to melt away before anything concrete is agreed. And all the time the threat of the low cost carriers (LCCs) gets greater, even more so now that KLM had to sell its own LCC attempt for a pittance.

KLM, founded in 1919, is the oldest airline in the world still flying under its original name — but in what form will it reach its 100th anniversary? KLM has a 100–plus strong fleet, currently all of which are Boeing or MD aircraft (see table, page 9), making KLM the only European flag–carrier not to use Airbuses, though this is soon to change. The airline is undergoing a complete renewal of its long–haul fleet, starting with 10 777- 200ERs and three 747–400ER freighters, which are replacing 747–300s and MD11s by the end of 2005. The 777s are coming on 12–year leases from ILFC, from whom KLM already leases several aircraft. In November 2002 KLM also confirmed an order for six A330–200s, with "rights to purchase" (as opposed to options, which impose more financial obligations) for another 18. This is the second part of the long–haul renewal process, and these aircraft will arrive in 2005–2010, helping to replace eight MD11s and 12 767–300ERs over the period. KLM will place a third order at some point, for either more 777s or A330s.

Despite its size, however, KLM is a vulnerable airline, weighed down by two strategic disadvantages.

First, its natural catchment area is small compared to its key rivals — BA, Lufthansa and Air France — and second, Schiphol, its home base and hub, is a high cost facility, burdened by high landing fees and slow turnaround times.

Not surprisingly, the two factors combine to ensure that Schiphol is not as profitable for its flag carrier as the hubs of its three main competitors (see Aviation Strategy, September 2002).

Even with transfer passengers, Schiphol trails in fourth place behind its major hub rivals in terms of total passengers served (with 39.5m passing through Schiphol in 2001, as opposed to 48m at Paris CDG, 48.6m at Frankfurt and 60.7m at Heathrow). Moreover, expansion plans at Schiphol always face fierce environmental opposition.

By KLM’s own calculations, its 737 cost per seat is 40% higher than its European LCC competitors, so although revenue per seat is approximately 20% higher at KLM than the LCCs, its margin is comparatively much worse than its rivals. There is a general push towards replacing unprofitable short–haul routes with high–speed train routes as soon as possible, and KLM has a joint venture with Dutch Railways — called the "High Speed Alliance" — that will offer a three–hour train service between Schiphol and Paris from 2006.

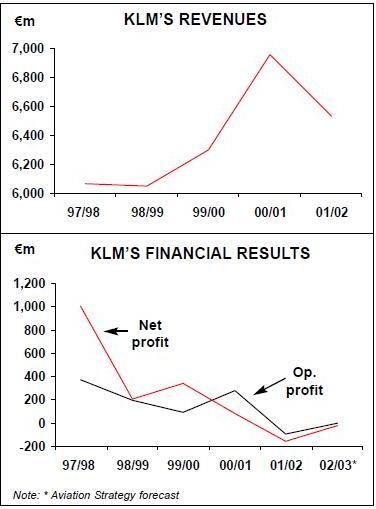

Until recently, however, KLM had coped well with its structural disadvantages, and the group racked up substantial profits in the late 1990s (see chart, page 8). Then came September 11 and KLM reacted by reducing FTE employees by 1,200, cutting back the working week for three months and easing back capacity by around 10%, which came on top of a planned 5% reduction in capacity that had been agreed even before September 2001.

KLM also sought temporary alliances and partnerships wherever it could, including a code–sharing deal with Continental, and handed over some transatlantic operations to Northwest. Nevertheless, KLM estimated that September 11 knocked approximately $55m off its bottom line.

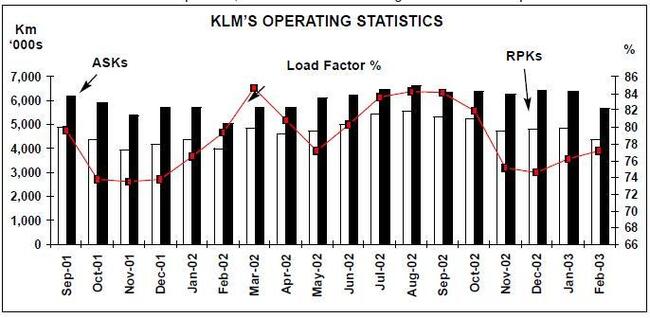

By the second quarter of 2002 KLM’s traffic had recovered to pre–September 11 levels, yet there were few signs of breaking back into profit.

After posting a €63m operating loss for the third quarter of 2002/03 (October–December 2002), compared with a €76m loss in the corresponding period of 2001/02, KLM warned that it was likely to make a loss for the full year, primarily due to poorer- than–expected RPKs and yields.

That has resulted in further trimming of capacity, as well as further cost cutting. The airline now says it is unlikely to make an operating profit in 2002/03 (KLM’s fourth quarter is traditionally its weakest, and full year results will be released in May), which had been its expectation earlier in 2002.

In 2001/02 KLM posted a € 94m operating loss and a € 156m net loss. Of the operating result, passenger operations (KLM and its various airline subsidiaries) accounted for a substantial € 208m loss.

That passenger operating loss compares with a € 32m loss in the 2000/01 financial year and a € 72m profit in 1999/2000 KLM’s 2002/03 net result will also be hit by the substantial compensation it has to pay Alitalia following the Dutch airline’s unilateral termination of an alliance between the two in April 2000.

An arbitration court ruled that Alitalia had to pay KLM € 100m to compensate for KLM’s investment in Milan Malpensa airport, while KLM had to pay Alitalia €250m (plus interest) for breaking the alliance agreement. KLM suggested that it gave Alitalia services in kind, instead of cash, if it joined the SkyTeam alliance, but Alitalia responded that it would prefer the cash. The final total that KLM has to pay is just short of €200m, and it is expected that this will come out of the 2002/03 results.

KLM’s cash balance was €951m at December 31 2002, similar to the figure 12 months before that, but this will be almost €200m lower when the full year results are announced, thanks to the Alitalia payment. And as at December 31 KLM carried almost €4.5bn of long–term debt, which gave it a worrisome net debt/equity ratio of 135%.

The low cost threat

Although KLM’s current financial situation is challenging, the long–term situation looks worse when the nature of the threat from the LCCs is considered.

The biggest LCC challenge comes from easyJet, which has a significant presence at Schiphol. In its 2003 summer schedule it operates 44 flights a day to/from Schiphol and Barcelona, Belfast, Edinburgh, Geneva, Glasgow, Liverpool, Gatwick, Luton and Nice. Ryanair too is a threat, with a mini–hub at Charleroi in Belgium and routes from the UK to Groningen and Eindhoven.

It is also establishing a base at Neiderrhein (near Dusseldorf), which will also capture traffic from the Netherlands, whose border is 45km away.

KLM argues that since more than 50% of its traffic at Schiphol are transfer passengers; it is less vulnerable to the LCCs than other airlines. That’s true, but KLM’s heavy reliance on transfer traffic is in itself a weakness, since those sixth freedom passengers have lower yields than point–to–point traffic. And KLM’s full service, high fare product is vulnerable to competition from the LCCs.

KLM says that only a small percentage of its routes face LCC competition, but that figure is approximately 10–15%, and load factors on these routes have suffered against the LCCs.

In any case, KLM last year began simplifying fare structures (from 25 to 8) and reduced economy fares on 20 of its 66 European routes.

Unfortunately, cutting fares without attacking the high costs KLM has to endure at Schiphol just erodes the airline’s margins, but is a classic sign that KLM is worried by LCC competition.

KLM launched Buzz, its own LCC, in early 2000, when the plan was to exploit the LCC opportunity by using spare capacity at KLM uk.

In November 2002 KLM emphasised that Buzz would be its LCC for the foreseeable future, offering more than 20 routes from low–cost Stansted (and, in 2003, from Bournemouth in southern England) to Germany, the Netherlands, Spain and France using BAe 146s and 737–300s. KLM also said that Buzz would have a fleet of up to 40 737s by 2005, confirming it as a strong third competitor to easyJetand Ryanair.

However, in a few weeks there was an abrupt about–turn by KLM. It appears it decided that the scale of investment needed to keep Buzz competitive against encroaching LCCs was too much, particularly — according to KLM — against "a lot of new low–cost entrants in Germany with big pockets of money". Conveniently, the loss–making Buzz had been separated out from KLM uk in November 2002, and so in January 2003 KLM announced it was selling the airline to Ryanair for $25.4m, although the net gain to KLM is just $5m since Buzz has $20m of cash. (However, the UK Office of Fair Trading has yet to approve the deal, and there are reports that Ryanair is trying to reduce the price since due diligence has allegedly revealed a worse situation at Buzz than anticipated.)

The sale acknowledged that KLM could not make Buzz into a real competitor to Ryanair and easyJet, but the abrupt turn in strategy also presents doubts about the competence of KLM’s senior management — particularly since it was only at the end of 2002 that executives were so keen on the LCC opportunity.

At that time Floric van Pallandt, the Transavia CEO, said that there was a "window of opportunity" for KLM, as he believed the LCC share of the intra–European market would rise to 25% by 2015. Leo Van Wijk, KLM President and CEO, was at the time highly critical of analysts that predicted KLM could not manage to run a LCC. Unfortunately for KLM, Van Wijk was wrong and those analysts were right.

Embarrassingly for KLM, still present on KLM’s website is an interesting and detailed presentation (dated October 20 2002) on the LCC sector, which explains the market opportunity for LCCs, particularly in Spain, Germany and France — markets that KLM admits it cannot serve using Schiphol as a LCC base due to its higher infrastructure costs.

Intriguingly, in its LCC analysis KLM claims that on a normalised leg length comparison, Buzz’s cost per seat was 22% better than easyJet’s, but 17% worse than Ryanair’s. KLM says this is due to Ryanair’s airport deals, higher crew productivity, economies of scale in overhead and marketing, and aircraft financing.

Now, the only low–cost capacity KLM has is through Basiq Air, a LCC offshoot of Transavia.

Basiq Air was launched in late 2000 and concentrates on continental Europe. But if KLM couldn’t get Buzz to work, what hope is there for the tiny Basiq Air? Unless Basiq Air is expanded greatly, the only possible response KLM has to the LCCs is cheaper fares, which without attacking Schiphol’s high cost base is a recipe for disaster in the long term.

Transavia is not a LCC option for KLM, given its Schiphol base, and in 2003 Transavia is concentrating on serving leisure destinations through charter and scheduled services, rather than serving as a traffic feed. It is adopting some of the LCC sales & marketing tricks, such as going ticket–less, and its sales are mainly through the Internet and via call centres.

However, given that Transavia’s new strategy was announced in October 2002, at the same time as KLM declared that Buzz would be built up as a real force in the LCC market, the commitment of KLM to Transavia’s new strategy could be doubted.

The problems KLM faces are illustrated by the London–Amsterdam sector. Last year, KLM said it would concentrate on high yielding point–to–point traffic from central London to Amsterdam, leaving Buzz to serve the Stansted–Schiphol route, where "just" 30% of passengers transferred onto longhaul KLM flights at Amsterdam. But with Buzz gone, that 30% feed traffic has also gone (KLM exel operates out of Stansted, but not to Schiphol), and meanwhile the higher yielding point–to–point traffic from London to Schiphol faces competition from easyJet at Gatwick. Much of KLM’s general feed traffic at Schiphol now comes from the merged KLM uk/KLM cityhopper.

There is one other possibility. There are plans for a start–up at Neiderrhein Airport using A320s in a JetBlue type operation. KLM might again try to break into the LCC sector by investing in this venture.

Alliance woes

That’s why KLM is redoubling its exhaustive efforts to join a major European alliance. According to Leo van Wijk, KLM is searching for "alignment with a strong European partner in a strong global alliance…while protecting KLM’s position at Schiphol as our main hub".

Despite its disastrous flirtation with Alitalia (see Aviation Strategy, July/August 2002), SkyTeam appears the most likely destination for KLM, although oneworld too is in the frame, and speculation shifts week by week. The only certainty appears to be that Star is not an option for KLM, given the Dutch airline’s fierce competition with Lufthansa in the catchment markets of the Rhine region.

A SkyTeam tie–up for KLM would fit in nicely with Northwest’s code–sharing alliance with Delta and Continental (Northwest’s close ally), and Northwest’s wish to join SkyTeam.

More importantly, KLM would bring its north European network to SkyTeam, and, in return, ensure strong feed to KLM from Alitalia in the south and from Air France’s network (particularly Air France’s transatlantic routes). The problem here is Air France’s hub at CDG, which many analysts see as being far too close to Schiphol for real benefits to flow to and from KLM.

As the two airlines are Europe’s kings of transfer traffic, the Air France suggestion is to prioritise CDG as the SkyTeam long–haul hub in Europe, relegating Schiphol to being a hub for intra–North European flights only.

That’s a big change in emphasis for KLM, and the political and indeed strategic risk in doing this may be too much for KLM’s current management.

A substantial equity deal or merger with Air France would be a different story, but short of that, any alliance could break down and it would be difficult, if not impossible, for KLM to rebuild a long–haul network that had been "handed" over to SkyTeam in the meantime.

The remaining option for KLM is BA/oneworld. Only last month BA and KLM declared (yet again) that they were not reviving merger talks, but that there are ongoing discussions about KLM joining oneworld. The fit between Heathrow and Schiphol would be slightly better than CDG and Schiphol, but transatlantic concerns mean that Brussels' regulators would be more concerned about a BA/KLM tie–up than AF/KLM. If the price of a BA/KLM deal was an abandonment of Wings, this would be difficult and costly to do given the integration of KLM and Northwest’s transatlantic operations.

In the last full reporting year (2001/02) the North Atlantic routes account for approximately 28% of KLM’s RPKs, the single largest sector, followed by Asia/Pacific (23%), Central/South Atlantic (15%) and intra–Europe (14%). For the KLM group as a whole, Europe contributed 37% of operating revenue and North Atlantic 17%.

Where next for KLM?

Now that KLM has learnt the hard way that the LCC market is competitive and brutal, what will it do next? With revenue under pressure from the LCCs, until (and after) KLM joins one of the global alliances the need to reduce costs is paramount.

Rob Ruijter, KLM Managing Director and Chief Financial Officer, calls it "strategic cost management", and the stated aim is to increase the ROCE to 9%. That’s a tough target — and some would say near impossible for an airline with KLM’s cost infrastructure.

In 2001/02, for example, the ROCE was — 3.9%, and on a like–for–like basis (assuming revenue and capital employed remain the same) KLM would have to strip out €787m of costs — representing 12% of its cost base — to achieve its ROCE target.

On April 1 KLM announced it was going to axe"several thousand" jobs, although the unions are unlikely to accept this lightly. Relations with the Dutch unions are already uneasy, and they were not impressed by the airline’s de–recognition of NVLT, the engineering union, in 2002 following a wildcat strike by engineers that cost the airline $10m, according to KLM.

This de–recognition has since been reversed, but further job cuts will destroy any lingering goodwill between the two sides. KLM is also trimming back capacity this summer, mostly via smaller aircraft and fewer frequencies on some routes, but this will hardly dent the cost target.

Unsurprisingly, KLM is light on the detail of where most of the cost reduction will come from, other than general comments about investing in aircraft to drive down unit costs and, according to Rob Ruijter, "building a shared employee culture in which cost reduction is viewed as an important, challenging and rewarding activity", and "being prepared to innovate in ways that dramatically alter the shape of the cost curve."

That kind of rhetoric has not appeared to go down well with KLM’s shareholders, and the fall in KLM’s share price has been steady and consistent, even before September 11. Quoted on the Amsterdam, Frankfurt and New York exchanges, from a high of almost €60 in the late 1990s, KLM’s share price fell to €22 prior to September 11 and has kept going down ever since, to around €6 at the end of March 2003.

That has given KLM the opportunity to buy back some of its shares, although this exercise is very modest. An alliance deal will take some of the pressure off the share price in the short–term, but with a high cost base and a limited catchment area KLM’s long–term survival may depend on a merger that would mean the end of the Dutch carrier’s independence.

| Fleet | Orders | Options | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A330 | 6 | 18 | |

| 737-300 | 15 | ||

| 737-400 | 14 | ||

| 737-800 | 13 | ||

| 737-900 | 4 | ||

| 747-200B | 2 | ||

| 747-200B Combi | 4 | ||

| 747-200F | 2 | ||

| 747-300 Combi | 3 | ||

| 747-400 | 5 | ||

| 747-400 Combi | 17 | ||

| 747-400LRF | 3 | ||

| 767-300ER | 12 | ||

| 777-200ER | 10 | ||

| MD11 | 10 | ||

| Total | 101 | 19 | 18 |