British Airways: the devilish detail of FS&S

April 2003

In the cyclical downturns of the last two decades, British Airways has reacted impressively swiftly and decisively to changing market dynamics. Perhaps equally importantly it has told the markets what it has had to do, why and when. In each case the actions it took allowed it to minimise the effects of the downturn and to recover faster than many of its rivals. In this current downturn, however deep it is likely to turn out, it is very likely that it will prove that BA has reacted with equal alacrity and equal results far ahead of its rivals.

In March, BA held its annual investor day at Heathrow for buy- and sell–side analysts.

During the day the company provided an update on the success of the strategy it had promulgated at the previous year’s event, entitled Future Size and Shape (FS&S), in the wake of the events of September 11 — see Aviation Strategy, March and December 2002.

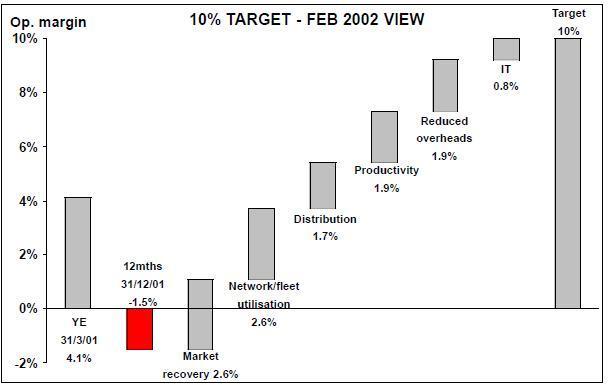

One of the main financial planks of this strategy is to return to a positive Cash Value Added (CVA) return. Because many people outside or indeed within BA do not understand the arcane elements of value added analysis, the management translate the financial targets to an operating margin target of 10%. Last year the CFO, John Rushton, showed how the strategy would allow the company to return towards this 10% margin target. Inherent within the assumptions was that the market would recover and they had pencilled in a 2.5% margin improvement from this.

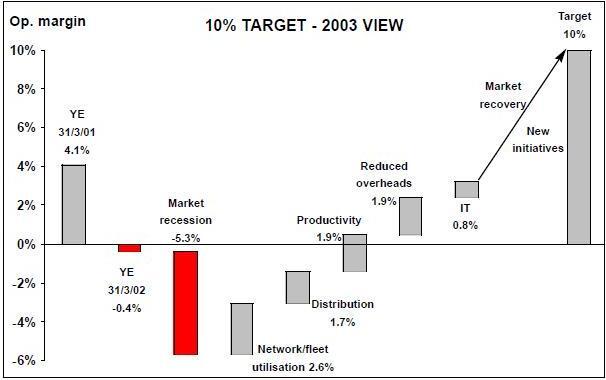

This year the company provided an update of the plan (see page 4) showing that in the intervening period market decline had removed a further 5+ percentage points from the margin. As a result the company has instituted further major cost cutting measures beyond its FS&S plans.

The new measures

These measures cover two main areas designed to shave a further £450m from the cost base:

1) Procurement As with many of the established carriers, BA carries much historic baggage. But it is always somewhat of a surprise to find new instances which one would have thought the management would have addressed before

. Last year the company was able to dismiss a large number of people from engineering functions because their main job was unnecessarily to rewrite manufacturers' manuals into BA–speak. This year they discover that they have another department dedicated to rewriting the pilots' aircraft operating manuals.

However, a far more important step is finally to develop a proper state–of–the–art procurement strategy. Here the company has identified the potential to cut its non–fuel costs by 10% (or £300m). It is a good accountancy adage that the purchasing manager is the one who makes a company’s margin. It holds good in an airline as well.

Up to now procurement at BA has been department based with no real overall control.

Each department has almost gone its own merry way in acquiring the goods and services it needed. The new element is to centralise the function with a process–led organisational structure to cover all areas of goods and service acquisition: it does not matter whether it is a lettuce leaf or a tonne of kerosene, the same rules should apply.

The aim is to have a far better control over the administration of price of goods acquired, the full assessment of demand control and the accurate specification of product need. Needless to say a large portion of this is designed to be electronic.

This represents a step change in company behaviour.

The company had some 14,000 separate suppliers. It aims to reduce this number to 2,000. Since implementation the company has reduced the number of suppliers by 64%, improved buyer productivity by nearly 50% and reduced the average transaction cost by 40%. Within the procurement strategy is the understanding that suppliers fall into differing strategic categories, varying from:

- the 100 or so strategic and monopolistic or oligopolistic suppliers such as airports and airframe manufacturers, where relationships need to be fully managed;

- to the 1000 or so commodity suppliers where the company can enforce product quality and price on a transaction only basis (and here already 80% of these supplier transactions are conducted electronically);

- to the 500 or so collaborative suppliers where the company can pass on to partners some of the under–utilised assets and inventory (such as contracting out the spares stock of A320 parts to Iberia or Concorde spares to Air France);

- to the 500 or so "opportunistic" suppliers from whom all is really important is the price. Already the company has held some 16 eAuctions on a spend of £18m with an implied saving of 25% — and this covering anything from stationery to crew hotac expenses.

2) Customer Enabled BA (ceBA) The second initiative is designed to remove a further £100m from the cost base over the next few years. This also derives from technological changes — and in this case the success the company has seen in its electronic booking system — and the inherent proposal in the FS&S programme to simplify processes.

The company stated that the aim is to "simplify contact with customers and drive out complexity, enabling customers to 'self–serve' when they choose to do so".

The complexity in the industry especially among the full–service carriers is awesome. For historic reasons there are millions of fare–types, BA has 26 selling classes, identifies 15 types of passenger and at least ten ways to pay. As a result it needs to train staff to a very high degree to act as translators to carry out transactions for passengers: and the answers the passengers get are not always consistent. As always, complexity slows change.BA appears to have been astounded by the success in the new booking engine it introduced last year (see graph, below).

The strategy in this area is another key lesson derived from the LCCs: a) simplify (KISS), b) enable self–service where possible, c) enhance service.

The company has set its targets. It aims to have all tickets electronic by the end of 2004. At the moment only 26% of tickets issued are paperless — although not all routes yet allow the facility and the proportion is nearer 40% on eligible routes.

The benefits of eTicketing are well known — the most important being the lack of need to fly bits of paper round the world to match up with payment dockets, let alone the need for ticket printers, ticket readers, the paper itself, and the staff–handling necessary. It also allows a much quicker audit trail and greater accuracy of data capture.

BA also aims to have 50% of passengers using self–service check–in by March 2005, up from a current 10–20%; 80% of passenger trip transactions available as self–service (and 100% of the frequent flier transactions). It also plans to cut the number of fare types by 50%, standardising restrictions and rates.

As part of the process to enhance the customer’s control of the travel process, it is further developing its online service, beyond the simplification it introduced last year. The new add–ons to the booking engine will provide a much clearer indication at the time of booking of what the product is, what the restrictions may be (and how it compares with the low cost offering).

It will also proactively remind the passenger with a pre–travel checklist a few days before departure, allow the customer to check in online and (eventually) print his own boarding pass.

For BA, it sees this as a radical further simplification of the business with the aim of an annualised £100m in savings within two years.

Success of FS&S implementation

BA appears to be well on track to achieve the management–planned changes under the "new" strategy.

The new short haul booking engine is working — almost better than expected. In April last year only 20% of short haul economy bookings were made online through ba.com, with 54% of bookings through the trade. By January this year, it had shifted to 46% through the trade and 41% directly online. Short haul load factors have improved each month since February 2002.

BA has de–hubbed Gatwick, and is well on schedule for the fleet simplification and repositioning, (see table, page 6). With the long haul and short haul fleet renewal plans now virtually over, there are almost no new aircraft to be delivered over the next few years. As a result capital expenditure is well down — and the company has cut capex further than originally expected — and cash flow rising. Whereas in the immediate aftermath of September 11 the company was throwing away some £2m per day, it has been cash flow positive at the operating line and should be net cash generative in the year just ended. Against the backdrop of weak demand BA has achieved £1bn (US$1.6bn) in cost savings in the P&L account. Last year the company had announced plans for disposals of some £900m by March 2004.

By December last year it had achieved £570m of this.

However, it had planned to sell more aircraft than the two widebodies it achieved — at this time of the cycle the market for widebodies is of course fairly narrow. As a result, capacity this year will be a little higher than originally planned. Net debt peaked at £6.6bn in December 2001.

This has been reduced by £1.4bn since then. In addition, the company has renegotiated its debt profile, locking in fixed low interest costs with the result that now 60% of its debt is fixed against 75% variable previously. Current liquidity stands at some £2bn — which gives it a lot of leeway.

Planned staff reductions are well on track with a 9,600 reduction in staffing levels by January this year. This has been achieved with minimal cost: the company has a relatively high natural turnover of staff and 43% of the fall out up to now has come from natural wastage and a further 16% from staff taking unpaid leave — with only 15% of the reduction through voluntary severance or early retirement.

However, the market dynamics have tumbled since the inception of the FS&S programme — not just due to war worries. The economies on both sides of the Atlantic are somewhat subdued and with the bear markets on Wall Street and Throgmorton Street, terrorist worries, corporate belt tightening and bankruptcy filings in the US, business traffic is well down and yields are under severe pressure. This has been exacerbated through the winter by very deep discounts appearing in the market — particularly on the transatlantic. As a result, the company is not expecting any revenue growth this year at best and certainly not until there is a turn in the economic and stock market cycles. The only saving grace — until the outbreak of war anyway — was the success on short haul economy: where up to the winter season there was a positive performance in short haul non–premium unit revenues.

Meanwhile, following the break out of the long–awaited and feared hostilities in the Gulf, BA has cut spring capacity by some 4% — and announced cuts of some 6% on the Atlantic. It has announced an acceleration of its manpower reduction targets — bringing forward the target date for the 13,000 reductions to September this year from March 2004.

Outlook

BA started its downsizing programme before the events of September 11 — it at least recognised the need for action, even if that action had to be dramatically enhanced after the terrorist attacks. It is lucky that in comparison with its European rivals it has the flexibility to cut staff in the way it can: but on past practice and current showing it is no luck that the management reacts quickly and firmly. Although the tough times have become tougher with the outbreak of war, BA is now better placed than many others to survive.

| Target end Mar | Achieved | Cum. target | ||

| '03 | Dec '02 | end Mar '04 | ||

| Staff reductions(mpe) | 10,000 | 9,619 | 13,000 | |

| Annualised cost savings achieved | ||||

| Staff | £350m | £335m | £450m | |

| Distribution costs | £45m | £55m | £100m | |

| Procurement/IT | £55m | £52m | £100m | |

| Disposals | £500m | £570m | £900m | |

| Summer '04 | ||

| target | Achieved | |

| Capacity | -9% | -7% |

| Gatwick capacity | -52% | -56% |

| Destinations | -15% | -11% |

| No of aircraft | -49 | -29 |

| Aircraft subtypes | -40% | -36% |

| Shorthaul utilisation | +10% | +8% |