Australasia market post Ansett

April 2002

The demise of Ansett after 60 years of operation, and the failure of the Tesna recovery plan (putting Anset(t) back on its feet) has left the Australasian market in the midst of a major change. Air New Zealand, now all but re–nationalised, is slimming back to its roots; Virgin Blue is in the process of taking over the position as Australia’s second force airline and Qantas in the short run can rule the roost.

Australia is an almost unique aviation market. It is a country with a small population of 15m people, 85% of whom live in the four main conurbations of Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane and Perth — yet the distances are huge and the 15% of the population who live outside these cities need air services to provide efficient transport links. As a result the domestic market can be highly profitable. And yet, the market has never been able to sustain more than two airlines.

Ever since domestic deregulation, every new start–up has failed: and the consensus was that, had Ansett not failed last year, the latest start–up Virgin Blue might have gone. New Zealand, with a population of 3.8m, is also highly urbanised. Half the population lives in Auckland, Christchurch and Wellington, nearly 30% of the population living in Auckland itself, and 75% of the population on the North Island.

Both countries have a vibrant inbound tourist market — heavily focussed on Europe, North America and North Asia. However, because of the very long haul nature of these markets, they are highly subject to competitive forces. Equally they each have a vibrant outbound tourist market.

A little bit of history

In the regulated era, Australia maintained a strict aviation policy — government–owned QANTAS (aka Queensland and Northern Territories Airline Services) flew all international air services (and could only carry odd leg passengers domestically), government–owned Australian (previously known as Trans Australian Airways) could only fly domestic routes and privately owned Ansett (50% TNT and 50% News Corp) could also only fly domestically. In 1990 Australia deregulated the industry as much as it could. Importantly it agreed a common aviation area with near neighbour New Zealand across the Tasman Sea. Following this, there was an effective reverse takeover by Australian of Qantas.

Up to then New Zealand only had its national carrier Air New Zealand (formerly Tasman Empire Airways). Ansett had previously moved in to provide domestic competition on the main New Zealand routes. Following deregulation Air New Zealand felt that it had to do something strategically to offset the competitive impact on the other side of the Tasman. Being so disadvantaged by its home base position at the ends of the earth it started using Brisbane as a transfer hub. Ironically, Qantas had won the opportunity to take a 20% stake in Air New Zealand’s privatisation in 1989 (in competition even more ironically among others with British Airways). ANZ meanwhile took the decision to muscle in on its part–owner’s turf by acquiring a 50% stake in Ansett.

This caused a typical aviation problem in that Ansett had started flying internationally and as Air New Zealand was not Australian it could not retain a majority ownership of the international services. A reasonable compromise was established allowing ANZ control over the domestic operations and minority interest in the international. In 2000 ANZ took over the remaining 50% of Ansett, frustrating Singapore Airlines which had wanted to invest in Ansett but ended up instead taking 25% of ANZ.

Qantas itself was privatised in 1995. In the pre–privatisation process British Airways won the beauty parade and took a 22% stake. Fairly swiftly, in anticipation of the development of the oneworld alliance, BA and Qantas established a joint venture and coordination on the Kangaroo routes. It wasn’t long before Qantas sold its stake in ANZ — and then took over operations of the Ansett New Zealand services.

Following the establishment of the Star Alliance, Air New Zealand and Ansett both joined in, with even closer cooperation with Singapore Airlines.

Capital market restrictions

As publicly owned entities, both Qantas and ANZ suffer capital market problems. In ANZ’s case this is more than averagely extreme. According to the normal bilateral agreements an international carrier to be designated and accepted on a route has to be substantially owned and operated by nationals of the home country. To satisfy this requirement it was necessary in ANZ’s case that a New Zealand company took a major stake. This was done at the time by Brierley Investments. New Zealand decided that foreign ownership could not exceed 35% of the equity to satisfy this rule and the share capital was split between A and B shares, with only the A shares ownable by New Zealand nationals.

This has now changed following the restructuring and effective re–nationalisation: the New Zealand government holds a golden share to guarantee route rights (the Kiwi share) and no non–Kiwi individual or company is allowed to own more than 10% of the equity.

For Qantas, the rules were set at a more relaxed rate — only if foreign ownership were to exceed 50% might there be a problem. In the event it was the same: since BA held a 25% stake only one third of the free capital in privatisation was available for international investors and two thirds had to be owned by Australian nationals. Neither the Australian nor the New Zealand capital markets are that large — the ANZ 'B' shares regularly attracted a high premium to the domestic 'A'; Qantas has on various occasions had to invoke the repurchase option allowed by its articles of association to maintain 50% national ownership.

There is now the start of debate in Australia about relaxing the foreign ownership cap (on the realistic assumption that ownership does not always mean control).

This seems to be a consequence of Qantas’s capital requirements over the next decade, the fact that Qantas has a market capitalisation in excess of BA’s, and approaching that of American Airlines and that the Australian stock exchange does not value transport stocks that highly.

However, although the ruling enshrined in the bilateral air service agreements has never been tested in international law, there is a reasonable (and nasty) tendency by other nations who feel hard done by to refuse traffic rights to any airline they may think to be outside the rules.

Qantas: exploiting its luck

Qantas has enjoyed great luck over the past two years. In 2000 it was the official carrier for the Sydney Olympics. In 2001 Ansett went bust.

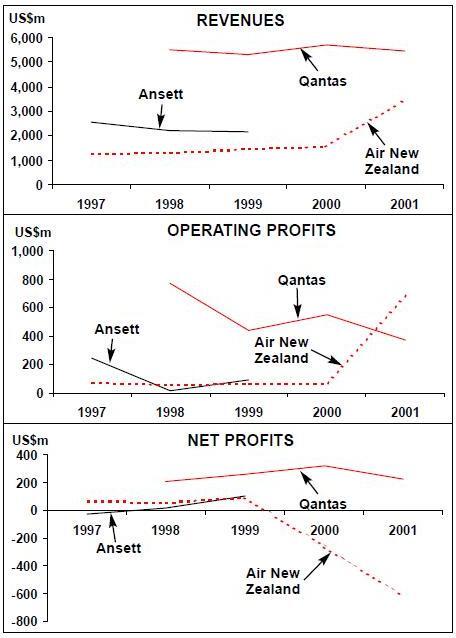

Following the demise of its erstwhile competitor it has been left with a 85% market share of domestic services, which is unsustainable (apart from anything else, it does not have the aircraft or the ground capacity). The demise of Ansett and the retrenchment at ANZ leaves the oneworld alliance the only one operating global services into Australia. The sole domestic competitor, Virgin Blue, is avowedly a low cost, no frills operator, which, by definition, cannot accept transfer or connecting passengers. Nevertheless, Qantas was hit in the aftermath of September 11- but overall comparatives are clouded by the excessive profitability achieved during the Sydney Olympics in the prior year period. In the six months to December 2001 the group achieved a year on year increase in revenues of 11% to A$5.7bn (US$3.1bn), a 16.5% increase in costs to A$5.4bn and a 42% fall in EBIT to A$270.5m and a similar fall in after tax income to A$153.5m.

Capacity grew by 6% and traffic fell by 2%. The group lost some A$15.5m on its international services with a seat factor down slightly to 76% and a like–for–like yield decrease of 2.6% compared with a profit of A$286m in the prior year period. This reflects a 30% fall in US traffic in the immediate aftermath. Domestic services in contrast showed a like–for–like jump in yields of nearly 6%, a near one point fall in load factors to 80.1% and a hike in operating profits 0f 53% to A$180m.

Qantas is reacting strongly to the change in the market dynamics. It is accelerating the disposal or retirement of older 747s (in the short term putting them into the domestic market where needed); it is deferring deliveries; and it continues to re–evaluate and rationalise non–performing routes.

However, the failure of Ansett has created an opportunity that it is now poised to take before Virgin Blue gets its act together to look at international services. It will be setting up a "low cost" international leisure airline for the next summer season, using the Australian brand, based in Cairns. It will start with a fleet of four 767s (with plans to increase this to twelve) flying initially to Japan, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Singapore and connecting to the Gold Coast.

This is an innovative attempt at creating a low–cost long–haul subsidiary. Other characteristics of the airline include:

- There will be a single cabin with relatively high density seating;

- The fare structure will be simple, but there will not be "very low fares";

- Rather than selling through the internet or call centres, Australian will rely on traditional distribution channels, but the in the second phase, probably involving service from Sydney, internet sales will be promoted;

- Free meals will be part of the service as will IFE, and it will offer a FFP;

- There may be an interlining agreement onto Qantas service;

- It has not yet been specified whether Australian will be associated with oneworld;

- All employment costs will be lower than at the parent, but it will not yet attempt to replicate the high efficiency levels of the successful low–cost short–haul carriers;

- It will normally operate on already–established routes, mostly replacing existing Qantas service, to smaller gateways;

- The routes on which it operates have bilateral restrictions in terms of entry and capacity;

- High aircraft utilisation may be supported by the availability of Qantas backup equipment;

- It may sell block belly space to Qantas but probably won’t have an independent freight service;

- Most of its non–core services — ground handling, catering, maintenance, etc. — will be outsourced to Qantas

ANZ: back to its roots

The company’s attempt to shore up its finances earlier in 2001 through the raising of a NZ$280m rights issue was not enough to allow it to continue — and at the beginning of 2002, the government stepped in with a NZ$850m bail out — leaving the state with 85% equity share.

As a consequence, Brierley and Singapore Airlines have each been diluted down to less than 6%. The management has been completely reshuffled and the strategy has been totally refocused to concentrate on the company’s roots.

It will have some serious strategic questions to answer. One of the main quandaries it has always suffered is how to maintain an effective long haul network — it only really works for operations to London (and maybe Frankfurt on good days). The traffic on the long–haul routes is primarily tourist and VFR and so very low net yield, while the flights cover half the circumference of the earth, which means that every airline in between is competing for the same traffic). However, it still maintains a slight cost advantage over Qantas for leisure routes into the Pacific region.

In the six months to December 2001 the group achieved revenues of NZ$2.6bn (US$ 1.1bn) down from NZ$4.3bn in the prior year period. Ansett was put into administration on September 12 2001, after which date the group could no longer consolidate the results. Like for like continuing operations generated revenues of NZ$1.8bn down 9%.

Group and ANZ operating results fell into the red with a group loss for the six months of NZ$174m compared with NZ$115m profit in the prior year period. For the six months the group suffered a net loss of NZ$377m down from a NZ$4m profit a year before.

Virgin Blue: finally a successful new entrant?

In 2000, following on from the successful sale of 49% of Virgin Atlantic to Singapore Airlines for a remarkable price, Sir Richard Branson set up a low cost operation — Virgin Blue — in Australia to provide services between the major city pairs. It was either wonderful foresight or great fortune to set up a low cost airline in a constrained and traditional market, and then have one of the duopolists fail.

It now has a fleet of 15 737s flying to Adelaide, Cairns, Canberra, Darwin, Gold Coast, Launceston (Tasmania), Mackay, Melbourne, Perth, Sydney, and Townsville. It has been doing reasonably well — and far better than any other new entrant into the Australian market, even though this is probably because it had not yet had the time to fail. However, following the Ansett and Tesna failure, it is pushed into the forefront. Virgin has sold a majority stake to Australian based Patrick Corp for A$260m, which will give it the domestic ownership to qualify it to fly internationally. As a privately held company there is very little financial information available, although it says that it is profitable.

Although Qantas may have taken the lead in announcing the establishment of Australian, it should not be long before Virgin expands out of the country. It is reputed to have had talks with Air New Zealand for a tie up in some form and is said to have been in talks with Star. Now with the backing of the Patrick Corp it has started talking about taking on some of the former Ansett assets — and is re–evaluating its future fleet needs. However, Virgin is a low fare, low–cost, single class airline using a single aircraft type. The danger is that it will be seduced into developing international routes requiring different aircraft types to try to compete with Qantas, that commit to linking into Star to provide feed, and that it will change what is potentially a very successful business model .

| In service | On order (options) | In store | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qantas | NZ | DJ | Qantas | NZ | DJ | NZ | AN | |||

| A320 | 16 | |||||||||

| A330 | 13 | |||||||||

| A380 | 12 (12) | |||||||||

| 737-200 | 3 | |||||||||

| 737-300 | 22 | 14 | 1 | 19 | ||||||

| 737-400 | 22 | 7 | 4 | |||||||

| 737-700 | 1 | 6 | 4 | |||||||

| 737-800 | 6 | 4 | 9 | 2 | ||||||

| 747-200 | 4 | |||||||||

| 747-300 | 6 | |||||||||

| 747-400 | 25 | |||||||||

| 747-400LR | 6 | |||||||||

| 767 | 38 | 13 | 8 | |||||||

| BAe 146 | 24 | 10 | ||||||||

| TOTAL | 124 | 34 | 15 | 40 (12) | 0 | 6 | 3 | 53 | ||