Has downsizing worked?

April 2001

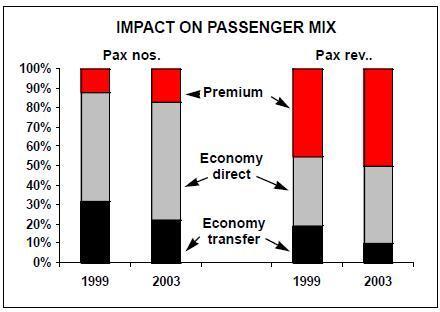

In the mid–1990s, British Airways started to see that it was going to encounter some serious profitability problems. It had been coasting for many years in the knowledge that it was the best of the European bunch, that it had a very strong natural demand of point to point passengers to and from its fortress at Heathrow, and that because it was operating under a relatively weak currency it had the opportunity to use its superior route network to attack the lower value but incremental transfer traffic through its two "hubs" of Heathrow and Gatwick — and this it accelerated following the fall of Sterling in the ERM crisis in 1995.

It had been growing capacity strongly based partly on the assumption that its alliance partnership with American would be consummated, that as a result it would have to accept open–skies, and that the restrictions at Heathrow and Gatwick would require it to have larger aircraft in order to maximise the use of its limited number of slots.

Neither of its main airports can be true hubs: they are both slot constrained, LHR with only two runways and LGW with one, neither has the possibility for new runways: it would be impossible for BA to try to establish a wave system to maximise interconnection potentials. However, the economics of its operations were weakening. It had seen its European operations results decline into losses. It had already cut much of its n o n — e s s e n t i a l e x p e n d i t u r e through disposals and outsourcing and had little further cost–saving to find. Since privatisation it has always been highly profitable and shareholder–orientated and the management could see that it would be increasingly difficult to maintain improvements in returns to shareholders while unit costs grew faster than unit revenues.

In addition, the competition was becoming serious. Many were seen to have matched BA’s product quality, while its own quality standards had slipped. It was "going through a bad patch". Lufthansa was achieving the success in generating a global alliance that BA lacked, had seriously improved its market offering and had started to make Frankfurt and Munich into really competitive hubs (although it did not have the point to point market of which BA can boast).

Whereas ten years before, BA had the largest number of gateways available in the US of any European carrier, and could boast the largest international number of destinations, with London being the first landfall city destination for many long haul flights, the competitors were increasingly developing routes that bypassed Heathrow and the code shares available to its European competitors from their anti–trust immunity status removed the gateway superiority that the company previously could boast.

In addition, Air France was finally starting to get its act together in its target towards profitability and privatisation. It uniquely had the potential to offer a really competitive hub in that it had a good level of point–to–point demand at its base in Paris as well as the space and the political will to develop CDG into a strong wave–based hub of operations (the fourth runway comes on stream this year).

Furthermore, the terminal capacity that would be provided by the fifth terminal at Heathrow will not now be available before the end of the current decade — and Heathrow needs the capacity for handling passengers now.

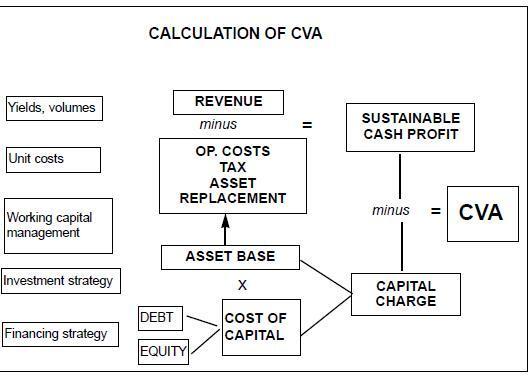

BA started a major review of strategy. The main plank of this review was a corporate financial target of Cash Value Added returns — to enable the proof that the company was not destroying capital in any element of its business. Simply speaking it needs to achieve a real CVA return in excess of its weighted average costs of capital (WACC) of 7% post tax. On top of this the company uses this financial tool to put their own results into context, to provide the basis for decision making particularly in capital expenditure, acquisitions and disposals, and in analysing their own business. The company’s results were falling far short of the target: there were three ways to improve the returns: raise revenues, cut costs, cut capital employed in the business.

This financial strategy was applied to all segments of the business. For the passenger business is emphasising the improvement in revenues and the reduction in capital.

The company tried to identify each of the major demand segments, the assets and asset value applied, and the returns achieved. This has always been difficult even in an industry with such a plethora of data. The prime difficulty is in applying the correct algorithm for the allocation of costs and revenues accurately over multi–segment flights.

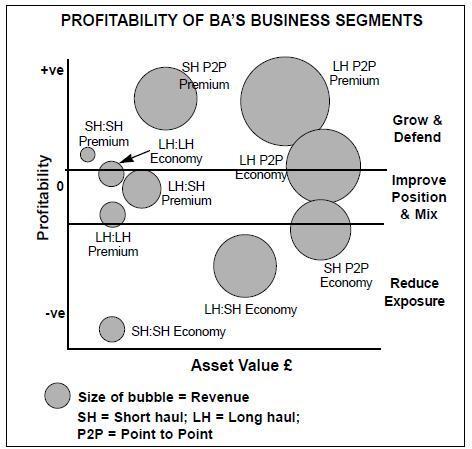

The simple form of the analysis split the demand segments into a three dimensional matrix of Long Haul and short haul, point to point and transfer, premium traffic and economy.

The revenue and profitability were then compared to the estimated asset value employed in the acquisition of each demand segment. The chart of this analysis, originally reproduced in the March 2000 issue of Aviation Strategy, has become known as Spurlock’s Balloons after the company’s strategist.

From this BA could prove to itself that it could not afford to concentrate on acquiring short haul to short haul, or long haul to short haul economy transfer traffic — and even short haul to short haul point to point economy traffic was destroying value.

The brave element of this analysis was the attempt to turn the traditional view of airline operations on its head: that the acquisition of marginal traffic was important as long as the marginal cost of acquisition did not exceed the marginal revenue acquired. In doing so it showed the promise of applying a modified form of enterprise value added analysis to the airline business.

The conclusions available from this analysis were aided substantially by Boeing’s introduction into service of the 777 (and for that matter Airbus' introduction of the A–330). For the first time in the Jet era, there was a new aircraft that offered a lower seat unit cost without having more seats. BA’s previous long haul strategy had relied on the 747. To feed the transfer traffic from short haul onto long haul it needed relatively large short haul aircraft. To acquire the traffic to fill the seats on the large long haul aircraft it needed to discount.

In the words of the company strategist, "bulk seats do not make returns to shareholders, frequencies, destinations and a premium product do".

The conclusion was simple: downsize and concentrate on premium traffic. The company switched existing 747 orders to slots for 777s. It decided to accelerate its capital expenditure programme substantially to replace the older 747s with 777s. It introduced a new sub–fleet with the decision to acquire aircraft from the A320 family to replace the older 737s and 757s.

It developed a route strategy to remove exposure to non–performing destinations, cut individual flight capacity and increase frequencies. When the strategy was promulgated, the company was unfairly criticised for turning its back on the economy leisure passenger. It is not. It is accepting that its shareholders cannot allow it to afford to fly passengers at a loss.

The conclusion was simple; but turning a ship around as big as an oil tanker going at full speed is not, and the implementation took time. The board took the decision on the new strategy towards the end of the 1998 financial year. The fruits are just starting to show.

Product

Once the analysis was there, and the conclusion to emphasise the acquisition of premium traffic, the company had to consider raising the level of its premium class offering well above the competition. Since privatisation BA has been strongly brand market oriented, maintaining a portfolio of brands specifically targeted to its demand segments — and as such is one of the few carriers world–wide that has successfully segmented its brands.

One of the main trends in consumer marketing is that product life cycles are shortening and that brands need to be relaunched increasingly frequently. Since the last introduction of its business brand "Club World", the competition had caught up. Many had dispensed with a first class offering and now provided a business class space and comfort level substantially higher than BA’s — effectively equivalent to the first class offering of 25 years ago.

BA needed to revamp a tired brand. It stood the equation on its head and designed a business class product nearly equivalent to a first class product on any other carrier. It took a close look at what its business passengers wanted on long haul: the ability to sleep, to work and relax. As a result it patented a seat that like its first class product reclines to a flat bed; it introduced privacy screens; it provided laptop power points.

The roll–out of the brand has been slow and connected with the timing of the delivery of the 777s and major checks on the newer 747s. The first aircraft embodied with the new configuration took off in March 2000 — and initially flew on the company’s busiest North Atlantic routes. BA has now fitted out 35 of its long haul aircraft with the new club beds including the first nine 777s. All aircraft on flights to HKG, SFO, MNL, TPE, ORD, JFK, EWR, NRT are fully embodied. Those on routes to IAD, LAX and JNB are in the process of embodiment.

The new Club brand offering then produced an additional problem — one that perennially appears in upgrading a sub brand. The new club class could be seen to detract from the first class product. As a result it was necessary to relaunch the first class product to maintain the apparent differential in pricing from the business class offering. The improvements include in seat power, better lumbar support, in–seat telephony and a redesigned cabin interior.

At the same time the company introduced a fourth class. This is in recognition of the number of passengers who travelling on business fly in the back of the bus but effectively pay the full economy fare. (It is never really nice as a traveller to find that whereas you paid $1,500 for a flight the guy next to you paid $300). The new World Traveller Plus cabin offers more leg room and the equivalent almost of the early business class products.

With the new route strategy, the company also refurbished the short haul business brand: Club Europe gained new leather seats, new interiors and a new catering product. The new aircraft fittings include much larger overhead bins and the company allows a friendlier hand baggage policy. The roll out started in the summer of 1999 and completed in autumn 2000. The result has again been a jump in customer satisfaction market share and revenue.

Scorecard

The conclusion must be that the strategy has started to work — and that this is starting to be felt in the results. The airline’s capacity has now peaked and is set to fall over the next two years. Unit revenues have started to rise strongly. Although — as is usual when an airline shrinks — unit costs will rise, it appears that on balance unit revenues should rise faster and that BA should finally be able to achieve a positive gap between its WACC and CVA return. One consequence of a reduced exposure to back–of–the–bus traffic may well be a lower cyclicality in its returns and may provide some defence against short term fluctuations in leisure demand. Downsizing in advance of a recession now appears to be a sound strategy, but the big unknown is the effect of intensified competition for business travellers.

| LONG HAUL | 747-400 | 777 | ||

| Pax | Price | Pax | Price | |

| Premium | 40 | 950 | 40 | 950 |

| Economy | 210 | 160 | 130 | 70 |

| Average | 285 | 350 | ||

| Price per pax | +23% | |||

| Load factor | +3 points | |||

| Rev per seat | +30% | |||

| SHORT HAUL | 757-200 | A320 | ||

| Pax | Price | Pax | Price | |

| Premium | 30 | 216 | 30 | 216 |

| Economy | 92 | 61 | 85 | 63 |

| Average | 99 | 103 | ||

| Price per pax | +4% | |||

| Load factor | +6 points | |||

| Rev per seat | +13% | |||

| IMPACT ON LONG HAUL ROUTES (Oct-Nov 2000) | |||||||||||||||

| ASKs | Unit Rev. Profit | Fleet change | |||||||||||||

| LGW-US | -14% | +48% | +£2.5m | 747-200 to 777 | |||||||||||

| LHR-US | -8% | +24% | +£1.8m | 747-400 to 747-200 | |||||||||||

| LHR-Asia | -37% | +53% | +£1.7m | 747-400 to 777 | |||||||||||

| IMPACT ON SHORT HAUL ROUTES (Oct-Nov 2000) | |||||||||||||||

| ASKs | Unit Rev. Profit | Fleet change | |||||||||||||

| LHR-Scandinavia | -21% | +35% | +£2.1m | 767 & 757 to 757 and A319 | |||||||||||

| LHR-Mediterranean -15% | +31% | +£1.9m | 767 to 767 & 757 | ||||||||||||

| LHR-Benelux | -13% | +42% | +£1.7m | 757 to A319 & 737-400 | |||||||||||