SAS: more pragmatic version of Carlzon's dream

April 2000

Under the charismatic leadership of Jan Carlzon, SAS in the 80s was at the forefront of airline strategy and thinking. Today’s pre–occupation and obsession with global alliances and seamless service had its foundation at SAS. However, SAS itself, despite its innovativeness, has yet to find a consistent profit formula.

Carlzon’s dream was for SAS to escape the confines of the relatively small domestic Scandinavian market and become a global player. A strong balance sheet supported these expansionist ideals, and a spending spree saw SAS taking stakes in Continental Airlines, British Midland, LAN Chile and entering a close co–operation agreement with Thai. SAS set out to build a network of intercontinental routes that linked its equity partners.

Carlzon believed that SAS should not just be an airline but offer its passengers a total travel experience — hence the airline’s continuing passion for airport lounges and its own hotel chain. He was also obsessive about service levels and his employees recognising the importance of morale, a lesson that many of today’s CEOs would do well to re–visit. His book on the subject was a best–seller in Scandinavia (though it was a bit of a dull read), and Carlzon became the most sought after speaker on the aviation conference circuit.

But the dream foundered on the harsh economic realities of the recession of the early 1990s. SAS was forced to re–trench and more hard–headed businessmen replaced the visionary Carlzon. Carlzon was undoubtedly ahead of his time and ahead of where politicians, shareholders, bankers and regulators would allow his airline to go.

The post–Carlzon version of SAS was a far more pragmatic airline with a less glamorous strategy. The issues facing the airline in the early 1990s were:

- A high cost base;

- European liberalisation;

- An affluent but small domestic marketplace;

- The failure of the global strategy;

- A heavily unionised workforce The new strategy for the 1990s veered away from expansion and concentrated on defence. Accepting its high natural cost base, SAS was to adopt a strategy of offering a high product level which would generate high yields. It was a standing joke that the curtain on an SAS flight was always nearer the back of the aircraft than the front. The network between the three capitals- Oslo, Copenhagen and Stockholm — was known as the "golden triangle" and allegedly produced some of the highest yields in the industry.

The product offered by the airline remained as high as during the Carlzon era. Relaxed, stylish and informal were the buzzwords used by the airline to describe its in–flight and on the ground product, and very importantly this was backed up with a generous and innovative frequent flier programme. Also SAS chose to be at the leading edge of developments such as ticket–less travel.

Unfortunately for SAS, the high yields generated in Scandinavia were always going to attract other carriers. SAS has done its best to discourage competition, with an understanding that it would always carry amount of its assets in liquid form (i.e. cash) which would enable it to match any fares available in the marketplace.

Defensive cooperation

Jan Stenberg, President and CEO, confirmed this in 1997, stating that "I wish to make it entirely clear that SAS intends to defend its home market with every means at its disposal, and that it we will do so aggressively." It not altogether surprising that Braathens Sweden has complained so bitterly that SAS has been guilty of predatory pricing on certain domestic Swedish routes (see Braathens Briefing, March 2000). The second part of this defensive strategy has relied upon SAS either co–operating or acquiring competitors or potential competitors. SAS itself has acquired:

- 63.2% of Norwegian regional Wideroe Flyveselskap;

- 36.5% of Latvian carrier Air Baltic;

- 100% of Finnish regional, Air Botnia;

- 26% of Danish carrier, Cimber Air;

- 37.5% of Greenlandair;

- 49% of Spanair, based in Palma:

- 20% of British Midland (down from 40% having sold half its stake to Lufthansa); and

- 25% of Skyways, based at Linkoping. In turn Skyways has taken control of four other Swedish regional carriers in the past two years:

- Flying Enterprise which is a direct competitor to Braathens Malmo Aviation at Stockholm’s Bromma Airport;

- Air Express based at Norrkoping;

- Highland Air (91% owned) based at Hultsfred; and

- City Airline, thereby inheriting orders and options for five ERJ–145s.

These developments have also raised concerns. Sweden’s competition board, the Konkurrensverket, in a general report on Swedish competition issues, recommended that SAS be forced to sell its 25% holding in Skyways holdings.

The cooperation strategy is best exemplified by SAS’s decision in 1995 to take Lufthansa as its major European partner. Speculation ahead of SAS’s announcement had suggested that Lufthansa was too big and too close to be a partner and KLM was most people’s favourite contender. However, SAS chose Lufthansa, and most commentators agree that the two airlines benefited from a favourable ruling by the European Competition authorities. Although SAS and Lufthansa were informed that they must give up slots if necessary to allow new competition on certain Scandinavian to German routes, so far no airline has been brave enough to step forward to make a meaningful challenge to the two carriers. In the light of this experience, last year the Commission conceded that in future policy making in this area it might consider guaranteeing a new entrant market share to encourage competition. The co–operation agreement between the carriers has according to SAS "strengthened the profitability of traffic to and from Germany".

The route networks of the two carriers fitted together well. In the early 90s SAS had cut back heavily on its unprofitable long–haul services, so the entry into Star enabled it to again market a wide range of US destinations, albeit on aircraft operated by Lufthansa. From Lufthansa’s perspective, SAS’s feed traffic was an important element in the rapid growth of its Frankfurt hub. The alliance with Lufthansa was extended in 1996 to United and Thai, and Air Canada in 1997.

While accepting SAS would never be at the lower end of the scale of European airlines on a straight cost comparison (even after stripping out its natural disadvantage of a short–haul route network), the management has tried to lower unit costs. This has proved a difficult task because SAS is heavily unionised, Scandinavian culture is scarcely workaholic, and the 50% of the capital of the airline remains under tri–government ownership. Nevertheless, the management have been prepared to, when necessary, endure strike action to improve unit costs.

The impact of competition

The now politically incorrect claim to be the "Businessman’s Airline" has remained the company philosophy. SAS put yield before capacity utilisation, with destinations, frequencies and flight times planned to satisfy the full fare business traveller. SAS was certainly right in believing that its home markets would attract new competition. For example, in 1996, SAS faced eight new competitors in the Scandinavian market. More competition, more capacity and lower fares were the inevitable conclusion. The result for SAS was that for the first time in its history it experienced stagnation in yield due to competition rather than from external causes such as economic slowdown.

The fiercest competitors for SAS have been Braathens and Finnair. The former, backed by a 30% stake held by KLM has been keen to expand from its historical role serving primarily the Norwegian market. Finnair too wanted to expand its sphere beyond its home market, and somewhat understandably it looked west rather than east.

Gloom and disappointment

Battles fought between these carriers have been fierce and bloody, but there are some signs that some stability may return. In the Norwegian domestic market, where Braathens and low cost operator Color Air (now bankrupt) have fought hard for market share in recent years, capacity fell by 15% last year. SAS was also able to increase its load factors in both the Danish and Swedish domestic markets. SAS reported its 1999 full year figures in March this year, and in its own words has a "disappointing 1999". Overall traffic grew by just 1.6% but of far more significance business class traffic fell by 5%. Passenger load factor fell by 1.9 points and passenger yields continued their slide with a 2.4%.

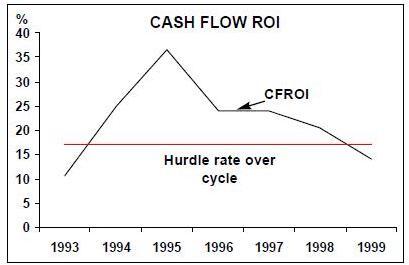

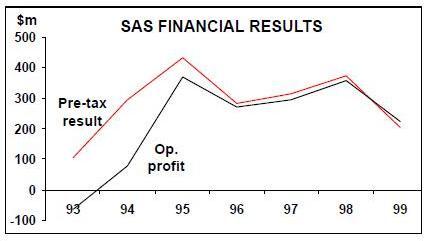

In operating cash flow terms, EBITDAR (earnings before interest, tax, depreciation, amortisation and aircraft rentals) fell by 26% on 1998. Operating income fell from SKr 2.99bn ($346) to SKr 1.66bn ($190m). Worryingly, in terms of Return on Capital Employed (ROCE) SAS managed only 9%, well below the hurdle rate (see chart) and the third year in succession to see a fall.

One of the few bright spots for SAS was the performance of its hotel division, Radisson SAS Hotels & Resorts (RSH). Loss–making in 1993, RSH has shown consistently improving levels of profitability ever since, and in 1998 contributed pre–tax income of over SKr 500m. This has been achieved even more impressively without recourse to the SAS balance sheet. In 1993 RSH had a balanced portfolio of over 30 hotels roughly equally split between owned, managed and leased. In 1999, although the RSH portfolio of hotels has increased to over 120, SAS owns fewer hotels in 1999 than it did in 1993. The spectacular growth in the hotels in the group has been achieved through managing and franchising, exploiting the recognised quality levels associated with the SAS brand. Returns measured by WACC (weighted average cost of capital) at RSH have now overtaken those achieved by the rest of the SAS group.

Long-haul reversal

The joint venture with Lufthansa continues to reap rewards. In 1999, traffic between Scandinavia and Germany rose by 4.8%, and the passenger load factor increased 3.3 points to 62.0%. Most significantly net revenues improved by a very respectable 9.1%. A reversal in policy for SAS is that it has decided to expand its long haul business. The decision has been supported by acquisition of A330/A340 aircraft that will be delivered from the second quarter of 2001 onwards. Four factors support this decision:

First, in its core home market, continuing yield erosion has reduced profit margins and SAS needs to look elsewhere to generate returns for its shareholders.

Second, the worst is probably over in the home market with some signs of a stable capacity/pricing structure emerging, which allows SAS to stop fire fighting and defending its niche position and consider expansion elsewhere.

Third, the Star Alliance continues to be the world’s leading global alliance, and the nine existing members will be joined by five new members in 2000. The Star Alliance brand has now gained global recognition, SAS now feels in a better position increase its exposure to the intercontinental marketplace.

Fourth, SAS feels its current market share of long haul traffic (because of the previous strategy of concentrating on the domestic market) is artificially low at 25%. The planned increases in the long haul fleet seek to gain a market share of about 30%.

SAS’s timing may be good. Asian traffic is recovering fast, and SAS will want to build an effective relationship with new partner SIA. The overcapacity in the Transatlantic market should ease in 2000 and a reinvigorated Air Canada (post Canadian acquisition) alongside United make very strong North American partners.

Cost control

The balance sheet will see a boost from the sale of half of its 40% stake in British Midland to Lufthansa that will produce a cash inflow of £91.4m ($150m). SAS will able to show a pre–tax profit of SKr 1000 gain on the sale of the stake. Cost control, as with all airlines remains a priority at SAS. The SAS programme, aptly or perhaps ominously, is named the Result Improvement Programme (RIP). Started in 1999 the aim of RIP is to achieve savings of SKr 3,000m ($330m) by early 2001. In 1999 savings of SKr 1,030m were recorded in areas such as distribution, air crew, overhead, maintenance, catering, IT and ground handling.

Fleet renewal programme

Fleet rationalisation

Alongside reduced fuel costs and lowered commissions, the RIP produced a 5.4% fall in unit costs in the fourth quarter of 1999. Taking 1999 as a whole SAS made the most progress in terms of cost savings in reducing commissions. Despite volume growth (albeit with a fall in business class traffic), SAS paid commissions of SKr 1,597m in 1999 versus SKr 2,175m in 1988, a 26.6% fall. Further cost savings are expected from SAS’s fleet renewal programme. The 141- seat MD–81 fleet is being replaced by the 174–seat A321s which as well as giving SAS more capacity are forecast to produce cost/ASK savings of 12 to 15%. Similarly the 72- seat Q400s which are replacing 46–seat Fokker 50s are expected to give unit cost savings of 22%. One area that is overdue simplification is the SAS fleet (see table).

The current fleet has two types of turboprops, which will be replaced with the Q400. The widebody fleet of 767s will in time be replaced by a combination of A330s and A340s. The real need for simplification is in the narrowbody fleet. SAS currently operates three principal types — DC–9s, MD 80/90s and 737NGs (and up until this winter a fourth type, the Fokker F28, could be added to the list).

With the DC–9s being phased out this year and next as the 737NG are delivered, this would have simplified the narrowbody fleet to two types. In something of a surprise move however SAS decided that it needed additional larger narrowbodied aircraft and that the A321 would be the replacement aircraft for its MD80 fleet. The aircraft will be used for long haul business expansion and for use into constrained airports.

SAS has also off–loaded some of its exposure through its joint venture with GECAS on 30 MD–80 aircraft. The joint venture gives SAS increased operating and financial flexibility. The deal releases capital, produces lower lease rentals today for the airline in return for giving up future book profits, and reduces residual value risk, whilst giving SAS long term access to the aircraft.

The capital expenditure programme amounts to some US$3bn, with SAS committed to spend an additional SKr 850m annually on non–airline related capex.

SAS will add about 2–3% capacity in 2000, and is hoping that a background of solid economic growth in Scandinavia and strong growth in countries such as Germany and Italy will produce RPK growth of around 5–7%.

Although some markets such as Norway are expected to show a fall in capacity, and Finnair is expected to follow oneworld partner British Airways in reducing capacity in 2000, overall SAS expects that the main trend in its marketplace will remain that of overcapacity. So it expects that its yields will continue to suffer at some 1–2% although this would at least be an improvement on 1999. Offsetting this forecast fall in yields, SAS expects to be able to show a fall in unit costs of at least 1%.

As a result, SAS expects 2000 to produce an operating income that is "considerably better" than that achieved in 1999. In this SAS will be helped by the strong performance of the Swedish economy, which is forecast to grow by 4% this year.

| Current | Orders Remarks | ||

| fleet | (options) | ||

| 737-600 | 29 | 11 | |

| 737-700 | 0 | 6 | |

| 737-800 | 0 | 13 | |

| 767-300 | 13 | 0 | |

| MD-80 | 75 | 0 | 8 phased out in 2000 |

| MD-90 | 8 | 0 | |

| DC-9-21/41 | 24 | 0 | Phase-out in 2000/01 |

| F.50 | 20 | 0 | Gradual phase-out |

| DHC Q400 | 1 | 21 | Replaces F50 and Saab 2000 |

| Saab 2000 | 5 | 0 | |

| A321 | 0 | 12(10) | From 2Q 2001 |

| A330-300 | 0 | 4 | From 2Q 2001 |

| A340-300 | 0 | 6(7) | |

| Total | 175 | 73(17) | |