Airbus prepares to bet the company

April 2000

Airbus has now received £530m ($850m) from the UK government as a contribution to the $12.5bn to launch the A3XX. The French, German and Spanish governments will later provide a further $3bn in launch aid.

That the notoriously stingy British Treasury under Chancellor Gordon Brown has allowed the money to be advanced is being taken as a sign that this ambitious project really has a commercial future. In private government ministers are less than ecstatic about having to provide risk finance to a huge company which already makes good profits as a near–monopoly supplier to the Ministry of Defence. But the prospect of securing 22,000 new jobs is politically appealing at a time when the UK government is facing embarrassment over severe job losses in the car manufacturing sector.

However, although the partners in Airbus (BAE, plus the members of the new EADS) have already spent nearly $600m on the new aircraft, they have yet to commit themselves to a bet that, in effect, puts the whole company at stake. Airbus’s chief executive, Noël Forgeard, is still sounding out airlines on whether they will be legally bound to buy the new aircraft. Depending on the response, the board of Airbus will decide in June whether to proceed with the marketing launch.

Even then, production (more or less certain to take place in Toulouse) would start only if enough airlines bought into the project. At the earliest, the first aircraft would not be delivered until late 2005. It would take around five top–class airlines and 30 orders to get the green light. Positive news is beginning to leak from Airbus headquarters in Toulouse: either this is all rose–tinted hype, or the project really does seem to have about 30 orders in the offing.

Under the 1992 US–Europe bilateral defining the conditions for government or quasi–government support for large aircraft projects, the Europeans agreed to cap launch aid for new aircraft to 33% of project cost. The rule is that the interest rate for three–quarters of the total 33% aid is the government–bond interest rates plus one per cent, with another quarter of the launch aid at one percentage point above short–term government–bond yields.

The fact that the terms are being kept secret, plus BAE’s assertion that it wanted continental European rates (lower than British rates at present), suggests that the rate may be lower than the rules allow. Privately, senior executives accuse the Americans of breaking the their side of the agreement (by receiving funds from NASA greater than the 3% of the company’s turnover as stipulated in the 1992 bilateral).

The implication is clearly that the terms could be very sweet for BAE Systems. BAE put pressure on the government by threatening to build the A3XX wings in Italy or Canada, whose governments, it claims, were willing to offer attractive deals.

Awkward questions

The Americans, who have tried hard to talk European governments out of backing this project, could now turn nasty. American trade officials are fuming that they have fared badly in recent disputes with the EU. The US could now up the stakes again by taking the EU to the WTO over its subsidies to Airbus, claiming it obtained an unfair advantage, irrespective of the bilateral aid pact. The case against gambling Airbus’s future (just as it is about to become a company with a value of about $20bn, 80% owned by EADS) is quite strong.

First, Airbus must convince customers that its planned savings in unit operating costs for the A3XX really are in the 15–20% range promised by the engineers. Some European airliners, normally prime prospects, state that they do not want the aircraft in the near–future. Normally, Air France and Lufthansa would be expected to be among the first buyers of a new Airbus. British Airways, an erstwhile fan, is no interested until Heathrow’s fifth terminal gets planning permission. United, which was supposed to be one of the launch customers, now says it has no plans to buy.

Second, the regular argument against launching the A3XX is, as Boeing never ceases to point out, the fragmentation of air travel markets and the associated downsizing from 747s to 777s and so on. Large aircraft suited a regulated market, in which the number of flights was artificially restricted.

Back in 1987 there was only one flight a day by a US airline between Chicago and Europe, a TWA 747 to London. And 60% of US carriers' transatlantic flights were by 747 operated by Pan Am and TWA in and out of East Coast gateway airports. Today United and American operate 21 daily flights from Chicago to 11 different European destinations, using 767 and 777 aircraft. The 747 share of a much expanded market is down to 40%. Boeing sees further fragmentation of the transatlantic market, with up to 160 addition direct routes identified for 777 and A330 types.

Moreover, Boeing predicts a similar fragmentation in the Pacific market. Currently two out of three Americans flying to Asia are destined for places other than Japan, yet 80% of flights are to Tokyo, where travellers then have to change. As Asia grows and deregulates, more point–to–point routes will open, especially as longer–range versions of the 777 and A340 come along.

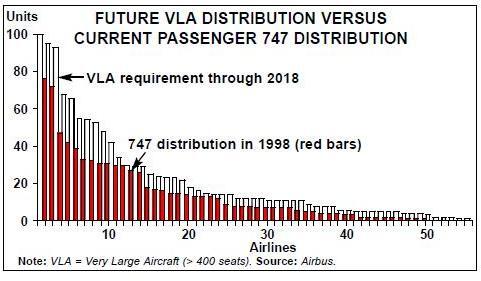

In essence, Boeing is saying that this changing market means that demand for aircraft of 400 seats and above is limited to 900 between now and 2018. Airbus acknowledges the fragmentation of the market, but argues that this development is complementary to potentially strong demand for large aircraft flying between key international hubs. It puts the market for aircraft of 400 seats and more is 1,200, and is confident it can win half of that from Boeing, even if launches a successor to the 747.

Airbus uses the standard 5% a year global traffic forecast to produce some startling extrapolations. For instance, the average annual traffic volume over the next 18 years traffic will be eight times the average of the past 30 years. The traffic increase between 2017 and 2018 could be the equivalent of total world air travel in 1969, the year the 747 was launched.

So the need for aircraft such as the A3XX is almost self–evident. Airbus speculates that the pattern of ownership of vary large aircraft in 2018 will be close to that for 747s today (see chart above).

Also, Boeing’s dismissal of very large aircraft seems at odds with its latest project, working with NASA, to build a flying scale model of revolutionary "flying wing" futuristic aircraft to try out whether a real aircraft of this time would fly, carrying 880 passengers. The $25m project is part funded by NASA.

And should the A3XX get underway, don’t be too surprised if Boeing itself finds an involvement through its close ally BAE.

According to John Leahy, the marketing director, Airbus hopes to win launch orders from two Asian carriers, one European or Middle Eastern airline and one American. At least one of the airlines would have to be in Star or oneworld. He says he is encouraged by the response from SIA, Cathay MAS and Emirates. Broad agreement seems to have been reached on these airlines each ordering 12–15 aircraft if formal commercial offers are made.

Also, FedEx, Cargolux, Lufthansa Cargo and Atlas Air are keen on a freight version of the A3XX because, with its ability to carry 150 tons over 6,000nm, so cutting a day off transport between Asia and North America. Given the big role of air cargo in feeding tight supply chains in electronics companies, this could be a powerful competitive weapon.