Canadian Airlines: a new beginning?

April 1999

Intense price competition in a small domestic market has meant chronic losses, extensive restructuring and a constant battle for survival for Canadian Airlines over the past decade. But can the Calgary–based carrier now build on its extremely low cost structure, close relationship with American and great alliance network to restore profitability? Will American help its partner capitalise and renew an ageing fleet?

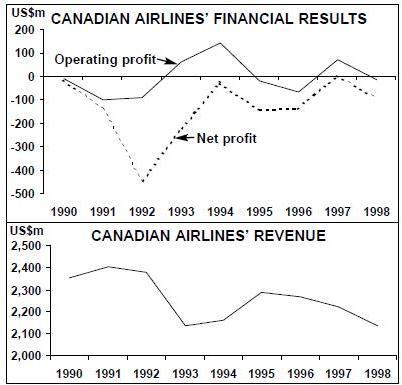

Canadian’s financial troubles began in 1989, when its predecessor — Pacific Western Airlines — overstretched itself by acquiring Wardair, an international operator, when PWA was still consolidating its earlier merger with five carriers. During the recession both Canadian and Air Canada accumulated massive losses as they fought out desperate market share battles.

As heavy cutbacks did not help, the two carriers were soon in serious merger talks. But these never came to fruition and in April 1994 AMR came to the rescue with a C$246m investment in Canadian (US$192m in 1994 exchange rates). This secured a 33% equity stake, 25% of voting rights and two board seats. The remaining equity and voting rights continue to be held by Canadian Airlines Corporation (CAC), a publicly traded and broadly held holding company.

The alliance offered network synergies: Canadian’s Asian routes complemented American’s Latin American and European operations. Canadian had also wanted to secure its future in an open skies US–Canada regime, while American got a lucrative service contract thrown in.

Canadian had limped through 1993 and early 1994 with the help of capacity cuts, executive pay reductions, loan guarantees from federal and several provincial governments and some debt–to equity conversions. But its finances continued to deteriorate as the Canadian economy showed no sign of recovery and price wars continued with Air Canada. The struggles were exacerbated by the entry of new low–fare carriers such as Nationair to key business markets like Toronto–Montreal.

By the summer of 1995, when Canadian’s cash reserves had dwindled to less than C$20m (US$13m), plans were formulated to cut costs by another C$325m through job losses, closing a pilot base, cutting marginal domestic routes and labour concessions. The airline also returned some 737s, consolidated heavy maintenance at Vancouver and terminated service to Shanghai.

The earlier financial restructuring rescheduled C$700m (US$464m) of debt, but too much of it had been “front–loaded”, which meant a sudden surge in payments in 1995/96. To raise cash, Canadian sold its Canadian Holidays tour wholesaling arm and started undertaking aircraft sale–leasebacks. By the end of 1996 it had raised C$177m (US$117m) from sale–leasebacks on 36 aircraft.

Between November 1995 and July 1996 Canadian secured new contracts with five of its six unions (excluding flight attendants) for a total of about C$125m in concessions. The deal with the pilots gave the union a board seat, no–furlough protection and profit–sharing when “significant” profitability is restored.

However, in contrast to the strong profit growth experienced by the US carriers in 1996, the situation in Canada continued to deteriorate. By the end of that year, Canadian had only C$68m (US$45m) cash, which would not last through the winter. It reported a C$187m (US$124m) net loss for 1996, which was only marginally lower than the previous year’s C$195m loss.

In late 1996 Canadian’s new CEO Kevin Benson and CFO Doug Carty (American CEO Don Carty’s brother) unveiled a new four–year restructuring plan that addressed four areas: cost control, revenue growth, capitalisation and fleet renewal.

The most urgent part of the plan sought C$200m (US$132m) annual cost savings over four years, the bulk of which were secured. Canadian’s workers agreed to an additional 10% pay cut for four years over and above the concessions they had made. The workers, whose pay was already among the lowest of major North American carriers, obliged apparently because the management used Carty/Crandall–style threats to shut down the airline if they refused. AMR contributed about C$70m (US$47m) over four years by reducing its annual service fee, while the federal and two provincial governments granted fuel excise tax rebates or reductions totalling C$38m (US$25m).

In early 1997 Canadian also obtained payment deferrals from enough lenders and lessors to survive through the leanest winter period. By the summer it had deferred C$170m (US$113m) in debt and lease payments due in first–half 1997 and secured a multi–year repayment schedule.

A major network realignment exercise using American’s advanced route planning models improved annual earnings by an estimated C$40m. This was achieved by matching aircraft size more closely to demand, while maintaining frequency in key business markets. F28s were redeployed in non–peak flying in shuttle markets, which freed 737s for more profitable transborder routes. As a result, domestic capacity fell by 11% and the average stage length rose by 22%.

All these efforts were at long last reflected in the bottom line in 1997, when the domestic economy also strengthened. Canadian reported a marginal net profit of C$5.4m (US$3.6m) for 1997 — its first positive annual result since 1988 — and improved its performance through much of last year. But the favourable trend was reversed in the fourth quarter of 1998 when a sharply higher C$149.7m (US$99m) net loss was incurred. This meant a return to heavy annual losses: C$137.6m (US$91m) for 1998. Like other major North American carriers, Canadian found that market conditions worsened on several fronts. Japan’s deeper recession hit the carrier hard because those routes account for 10% of its total revenues. Increased competition in western Canada and California contributed to a 10% decline in yield in the fourth quarter. The situation was aggravated by Air Canada’s deep discounting as it tried to regain traffic after its 11–day strike in September. In the second half of last year Canadian’s revenues were also adversely affected by the temporary loss of the AA- designator code on transborder flights due to American’s dispute with its pilots.

On the cost side, Canadian was hit by two new developments. First, the weakening of the Canadian dollar against the US dollar meant increases in payments for leases, aircraft parts, fuel and other items that are paid for in US dollars, effectively eliminating the benefits from the decline in fuel prices. Second, major changes in the way air navigation services are paid for in Canada led to a 45% hike in the airport user and navigation fees paid by Canadian last year.

Successful cash raising

Canadian must be congratulated for the perfect timing of its two recent cash–raising exercises. First, it completed a US$175m US high–yield debt issue in April 1998, soon after reporting its first annual net profit in 10 years. Next, it raised US$100m in an unsecured debt offering in July, just before it became evident that the Canadian domestic economy (particularly in the West) and industry conditions were deteriorating.

The two issues brought Canadian’s cash reserves more in line with industry norms: C$345m at the end of September, compared with just C$54m six months earlier. At year–end the company still had C$302.4m (US$200m) in cash, which provided an adequate cushion for the winter and made it possible to focus fully on building up revenues and implementing other key aspects of the business strategy.

But the money raised does not facilitate aircraft purchases as credit ratings remain junky (the latest issue was rated triple–C- minus by S&P and Caa2 by Moody’s). Analysts remain concerned about Canadian’s high leverage. Its long term debt and capital lease obligations were a substantial C$923m at the end of 1998 and the bulk of the fleet is on operating leases.

In November the carrier announced that it will add four (two new, two late–model) 767–300ERs and one A320 to its fleet in 1999. The 767s will be the first new aircraft added since 1995 and they will replace four DC–10–30s. However, these deals reflected exceptional leasing opportunities in the marketplace rather than the start of a fleet renewal programme.

Low cost structure, rock-bottom yields

Canadian’s persistent financial losses are unfortunate in the light of its successful cost–cutting. The past few years’ efforts have placed it among the lowest–cost major North American carriers. At 11.34 Canadian cents (7.5 US cents) per ASM in 1998, Canadian’s unit costs are now as low as Southwest’s.

Projects such as a planned joint–venture engine maintenance facility in Vancouver appear to offer some further cost–cutting potential, while expansion will help keep unit costs low. In late 1996 all collective bargaining agreements were extended till year–end 2000, so there is no immediate need to face the unions again.

The focus has shifted to the revenue side, because Canadian’s yields have remained extremely low due to intense competitive pressure from new entrants like WestJet, which began operations in 1996 and is showing staying power. Late last year its performance also eroded in the California markets following Alaska’s aggressive capacity expansion and price–cutting in Vancouver. In 1998 Canadian’s average passenger yield was just 13.54 Canadian cents (8.97 US cents) per ASM, when the range for the major US carriers was 11–17 US cents.

The obvious solution is to try to attract more high–yield traffic — now a priority for Canadian. The past year’s improvements to the premium–class service have included new seats on aircraft, refurbished cabin interiors, French–style meals, FFP enhancements and new domestic lounges at Vancouver and Toronto. All of that is encompassed in a new image, launched in January, which features a new “Proud Wings” logo — a stylised blue Canadian goose.

The cost of the total image–boosting programme is estimated at C$38m (US$25m) over two years, which the carrier says will be recouped from market share gains — a two–point rise in Canadian’s share of the C$2bn annual domestic business travel market would do the trick. The process will be helped by improved scheduling and increased service in key business markets. But experience south of the border has shown that improving the overall yield can be very tough.

Network and alliance strengths

Canadian’s biggest potential advantages are its valuable international route rights, close relationship with American and an alliance network that could turn out to be the strongest in the world. But can it build on those advantages enough to temper the many negatives?

The alliance with American, which enjoys antitrust immunity in the US, was both necessitated and made possible by the liberalised USCanada ASA, signed in February 1995, which introduced an open skies regime in stages. In contrast to Air Canada’s aggressive own–account transborder expansion, Canadian’s efforts have focused on co–operation with American.

The two now have an extensive code–share arrangement, involving 1,400–plus daily transborder flights. Its value to Canadian became very clear last year, when American’s dispute with its pilots in June led to the temporary removal of the AA–code from some 40 daily Canadian–operated flights for much of the remainder of 1998 (by January 1 the code was back on all flights).

Canadian’s international route franchise includes virtually exclusive rights to most of Asia and Latin America, as well as some European route licences. The government’s latest major policy announcements in June 1998 reinforced the traditional east/west division, giving Air Canada expanded rights from Toronto and Canadian from Vancouver.

The policy continued to protect Canadian’s strongholds, as Air Canada’s access to South America and Asia was limited to Brazil, Thailand and New Zealand in the short–term. However, as the markets grow and bilateral restrictions disappear, Canadian will increasingly have to contemplate operating in double–designated markets — the latest such route is Taipei, which Air Canada will be allowed to serve once the ASA has been revised.

Asia may be a more of a handicap than a help at present, but Canadian is tackling the challenge aggressively. This month (April) it is substantially expanding its hub operation at Vancouver, which it has been building into a gateway to Asia from North America. Last year US–Asia traffic there doubled (helped by robust Taiwan and China markets), while Canadian was the largest carrier by a wide margin. By rescheduling its own and code–share partners’ flights, Canadian is now creating five new banks of flights that will effectively triple, from 525 to 1,500 daily, the number of city–pair connections available through that hub.

Alliances are a critical part of Canadian’s future. It was fortunate in securing code–share relationships early on with all of the airlines (except Cathay) that later became the founders of oneworld. The 1994 deal with American was followed by one with BA in 1996, which has enabled daily flights to be offered in the five largest London–Canada business markets. Longstanding co–operation with JAL (a prospective oneworld member) is being expanded this summer, when Vancouver will be linked with Tokyo and Nagoya via 42 weekly code–share flights.

With American to the south, BA to Europe and JAL to Japan, Canadian has forged links with three of the world’s most formidable airlines. The South Pacific has been taken care of by alliances with that region’s leading carrier, Qantas (also a oneworld founder), and Air Pacific, which is 46% owned by Qantas. Although Canadian does not really need a Latin American partner, it has begun code–sharing with America’s partner LanChile on US–Chile routes via Miami and Los Angeles.

The delays experienced by American–BA will probably not affect Canadian a great deal, now that oneworld has taken off. Significantly, oneworld envisages Vancouver playing the role of the alliance’s principal gateway between North America and Asia — after all, American has extremely limited transpacific operations. To further enhance Vancouver’s potential and counter competitive threats in the West (sharply increased competition from Alaska, Air Canada’s talks with WestJet, etc.), Canadian has forged code–share deals with Alaska and Horizon and expanded cooperation with several feeder carriers.

Will AMR increase its stake?

The problem is that all the revenue boosting, hub strengthening and alliance building efforts will take time, and it is difficult to foresee significant improvement to financial results for some years. There is a need to improve liquidity to withstand a possible economic downturn and to upgrade the fleet. So when will Canadian get started with the capitalisation and fleet renewal parts of its four–year restructuring programme?

There has been much speculation that AMR might provide additional capital to increase its voting stake in Canadian. The US carrier wrote off its original investment two years ago and it is not easy to see what new benefits it would gain, but it is believed to be prepared to help out its partner. Also, the weak Canadian dollar has made the airline attractive to US investors.

But there are two potential hurdles. First, foreign ownership in Canadian is already at the 25% voting stock limit specified by the Canada Transportation Act, so the law would have to be changed. This may not prove insurmountable — or even difficult — but as of the end of March Canadian has not specifically asked the government to raise the limit because it does not yet have a deal.

The second problem is much harder to solve: vehement opposition from American’s pilots. The Allied Pilots Association (APA) is concerned about American’s plans to outsource flying to its oneworld partners. The union is already unhappy about what it regards as an imbalance in flying favouring Canadian, which it claims violates the scope clause in its contract. In response to the rumours that Canada might relax the foreign ownership limit, APA issued a statement saying that it was never in favour of the original investment and that it takes a “similarly dim view of a larger ownership stake”.

The union made an ominous reference to the recent dispute over American’s acquisition of Reno, which it said “takes on an added importance as a precedent–setting event in light of the news regarding Canadian”.

Since APA job action over the Reno deal cost it US$200–250m in lost pre–tax earnings in the first quarter, American will be treading carefully with any future deals. Canadian’s best hope may be to try to secure US financing from non–airline sources.

| Current fleet | Orders (options) | Delivery/retirement schedule/notes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 737-200 | 38 | 0 | |

| 737-200C | 6 | 0 | |

| 747-400 | 4 | 0 | |

| 767-300EREM | 10 | 4 | Four to be leased in 1999 |

| DC10-30 | 10 | 0 | Four to be replaced by leased 767s |

| A320 | 12 | 11 | One to be leased in 1999; 5 new aircraft in 2000; 5 in 2001 |

| TOTAL | 80 | 10 |