Consolidation pace increases for Europe's charter airlines

April 1999

The announcement of a planned $2.4bn merger of Swiss–based Kuoni and UK tour operator First Choice is just the latest round of consolidation in the European holiday industry — and one that has important implications for Europe’s charter airlines.

The Kuoni/First Choice merger was the culmination of months of speculation about the future of the UK tour operator, with rumours of interest from virtually every major European operator. But it was Kuoni that beat off the supposed competition from others, to secure a major position in the UK package holiday market — one of the two key European markets, along with Germany. If the deal goes through as planned by June (and there are rumours of a last–ditch Airtours bid), the new Kuoni Holdings, listed in Zurich and London, will be owned 53% by Kuoni shareholders and 47% by First Choice.

Charter fleet mergers

The deal further confirms what most charter airlines have known for a long time — that industry consolidation is inevitable (see Aviation Strategy, August 1998). And with tour operator consolidation comes charter fleet consolidation.

A prime example of this merger mania is provided by Thomas Cook’s purchase of the UK operations of US–based Carlson, for which Carlson is taking 22% of Thomas Cook in lieu of cash. Carlson’s UK operations include the 412–strong travel agency chain Carlson WorldChoice (previously AT Mays) and Caledonian Airways, which has valuable peak season slots at London Gatwick.

Thomas Cook says that Flying Colours (its existing airline, which incorporates the Airworld charter carrier) and Caledonian will be operated separately in 1999. However, a merger of the two airlines is the logical next step for Thomas Cook, and amalgamation is likely once this summer season has passed. Most analysts tip the Flying Colours name to be the survivor, but the combined carrier could well be called Caledonian as its brand recognition may be stronger among UK holidaymakers than Flying Colours is. The final decision is likely to depend on marketing surveys.

There may also be charter fleet implications from Thomas Cook’s other announcement — that German industrial group Preussag, which also owns tour operator TUI and the Hapag- Lloyd airline, will be taking a 25% stake in Cook for £400m ($640m), rising to 50.1% in late–1999. While Hapag–Lloyd and Flying colours/Caledonian are unlikely to merge in the short- to medium–term, there are obvious fleet synergies to be gained by utilising spare capacity in German or UK markets, joint purchasing, joint maintenance etc.

But it is within individual markets — particularly the UK and Germany — that effects of industry consolidation on charter airlines are most apparent. In the UK the Big Four — Thomson, Airtours, first Choice and Thomas Cook — went on a acquisition spree in 1998, sweeping up a dozen independent UK operators. This will result in their share of the UK outgoing package holiday market increasing from 60% in 1998 to an estimated 75% (at least) this year. (And the overall UK package holiday market rose by 12% in 1998 compared with 1997, with a similar increase forecast in 1999.)

This now means that approximately three–quarters of UK charter capacity this summer will be supplied by the respective airlines of the four UK travel giants — Britannia Airways, Airtours International, Air 2000 and Flying Colours/Caledonian. Monarch Airlines, controlled by UK operator Cosmos, accounts for another 15% of charter seats, which leaves just an estimated 10% of UK charter capacity to be supplied by independent carriers.

One source has estimated the number of non–aligned charter aircraft operating out of the UK this summer to be no larger than six aircraft. Much will depend on whether Thomas Cook allows Caledonian to continue to sell spare capacity to the independent UK tour operators. If Caledonian adopts the strategy of charter carriers owned by large rival operators (e.g. Airtours and Britannia) — which do not make capacity available to rival operators — then the independent tour operators will have great problems finding enough airlift this year, and they will have to charter their own aircraft. This is good news for airlines that provide adhoc spare capacity as part (but not all) of their core strategy, such as British World Airlines (where inclusive tour charters account for approximately 14% of annual revenue).

The independents’ last gasp

For independent charter airlines, the trend to consolidation may prove disastrous. Being non–aligned with a holiday giant means no certainty of contract. The large holiday groups are also squeezing margins on the marginal capacity the independents can offer, and competition between the independents is becoming even more cut–throat.

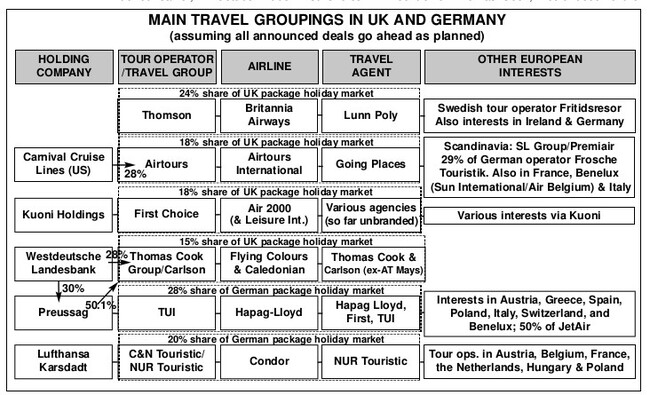

Since the last time (August 1998) Aviation Strategy published the diagram, below, of the UK and Germany’s main travel groupings much has changed. As well as the deals mentioned earlier, in October 1998 First Choice plugged its travel agency gap by signing a series of deals for regional agencies (which have yet to be amalgamated as a single brand). Thomson also floated in 1998 for £2bn ($3.2bn), although the share price rapidly declined until a steady recovery at the end of 1998 and the beginning of 1999. Airtours has raised £250m via bonds to find European acquisitions, while German operator Frosche Touristik (29% owned by Airtours) is planning its own charter airline for this summer season, using three A320s.

However, the recent flurry of deals has left one major continental European player without a UK interest — C&N Touristic, Germany’s so–called “Yellow alliance”. There are now just two major UK groups without a continental equity–linked partner — Thomson and Airtours. Until major shareholder David Crossland decides otherwise, Airtours is not in play, leaving Thomson as the most likely candidate for a Yellow alliance bid (particularly given Thomson’s erratic share price since flotation). If this deal ever came off, the current Big Six, soon to be the Big Five when Preussag takes control of Thomas Cook, would become the Big Four. And that would mean even less opportunity for Europe’s non–aligned charter airlines to survive.

And it’s not just in the UK and Germany where independent charter airlines are feeling the pressure. In Switzerland, for example consolidation has cut the number of tour operators from more than 20 to less than five — and this has put a corresponding pressure on charter airlines to merge as well (particularly as Kuoni now has its own airline — Edelweiss). TEA Switzerland is the latest to withdraw from the charter market, preferring to adopt the identity of easyJet Switzerland from April 1st 1999.

Late in 1998 SAirGroup paid an undisclosed sum for 49.9% of LTU, the German charter airline and tour operator, as part of its attempts to diversify and create a new European travel giant. (SAirLines also bought a 34% stake in Volare, a new Italian charter airline, in September 1998). But whether SAirGroup, an a non–EU company, can itself revitalise LTU Touristik (the loss–making tour operator) enough to join Europe’s Big Six travel concerns (and with the Preussag/Thomas Cook deal, this will soon be the Big Five) remains to be seen. What is much more feasible is a pan–European network of SAirGroup charter airlines (Balair/CTA out of Zurich, LTU — Germany’s third–largest airline — out of Munich and Dusseldorf, Sobelair out of Brussels) that can serve the established European travel giants.

Apart from SAirGroup, the only other European scheduled Major to be entering the charter market appears to be Alitalia, which is expanding the operations of Eurofly, its charter subsidiary. Eurofly is now operating long–haul charter with two new 767s — a move that puts it in direct competition with Italy’s largest charter carrier — Air Europe (now part–owned by Swissair.)

Going the other way is Iberia, which in October 1998 announced it was closing its charter airline, Viva Air, which had been making a loss for several years.

And the future?

It is important for strategists to look beyond the current holiday group/charter airline merger mania, and consider the long–term future of the industry.

Could there be fundamental trouble ahead for Europe’s charter industry? In December 1998 easyJet’s Stelios Haji–Ioannou forecast that charter airlines would no longer exist in the UK within 10 years. While many of Mr Haji- Ioannou’s speeches may be thinly–disguised marketing for his airline, in this case the arguments he has put forward bear closer analysis. He says that the European leisure market is slowly starting to resemble the market in the US, where there are few charter carriers and instead schedule airlines operate flights for tour operators on an ad–hoc basis. He cites two reasons for this change:

- Sophistication. Haji–Ioannou claims that European holidaymakers are moving away from the mentality of “turning up at Gatwick at four in the morning, going to the same hotel and eating the same food for exactly a week”. People want more and more choice, he says, and do not want to be told when and where they can go. And as more low–cost point–to point airlines come into existence, it will become much easier for people to arrange their own holidays.

- The demise of the travel agent. Haji–Ioannou says that the strength of the tour operator has been the travel agent, but that travel agents will continue to exist “only if they can add value”. He claims that this value is reducing all the time, particularly as Internet seat booking becomes more commonplace (see Aviation Strategy, March 1999, and pages 18–19 this issue).

These two factors will undoubtedly have an impact upon the European charter industry, but Haji–Ioannou is overstating his case when he says there will be no charter airlines in 10 years’ time. The demise of the European charter industry has been forecast many times before, but it has always managed to survive and expand. By consolidating into four or five pan–European giants, the leisure industry has signalled the death of the independent charter airline, but the carriers aligned with the megagroups are stronger now than they have ever been. Internet distribution and low–costs airlines will chip business away from the charters, but their parent tour operators have such a grip on key European holiday markets that the future of these charter airlines seems assured in the medium–term.