Virtually Yours ... British Airways?

April 1998

The concept of the virtual company is often dismissed by strategists as being too abstract to be of use in real life. Here Louis Gialloreto, assistant professor of marketing at McGill University, examines the phenomenon and considers whether one airline — British Airways — is making serious moves towards becoming the industry’s first virtual airline.

As the industry approaches the peak of the cycle, airlines inevitably start thinking about cost–cutting. In the last cycle many airlines carried out rather traditional slash and burn cost–cutting, but a relatively select few tried other more delicate methods — and one of these measures was the infamous outsourcing. Spinning off IT units, maintenance and engineering units, catering arms, charter subsidiaries and customer call centres, among others, became rather fashionable in the last cycle. But as soon as the industry hit a growth spurt these activities were reduced as airlines added resources in order to sustain market growth.

Yet some companies started taking outsourcing one step further; they moved towards becoming a virtual airline. In a virtual airline the ownership centre controls a brand and perhaps some key processes, but the rest of what an airline traditionally does is farmed out to subcontractors (i.e. pilots, flight attendants, call centres, aircraft ownership and maintenance). The theory is that an agglomeration of independent suppliers can provide contractually–guaranteed necessary service components more efficiently and to a higher average degree of quality than in–house resources can.

A poor track record

By and large the virtual airline concept was attempted most earnestly by new entrants (such as Greyhound in Canada), which were usually underfunded and rather naive about airline passenger service excellence. Despite low unit costs they were usually not able to attain either consistency and quality of service and/or solid initial funding, and so were never able to carve out enough market share to be considered as significant. Thus there has been no major example of a successful virtual airline so far.

But it would be a mistake to regard past and current failure of the virtual airline concept as a definitive guide to future prospects. When the next downturn approaches, airlines will start to reconsider the potential of any cost–cutting measures they believe may be useful, and outsourcing and the virtual airline will be no exception.

But the virtual airline is about more than just the cutting of costs, and airline strategists should ask themselves some key questions:

- Does one have to own the aircraft or be able to service the aircraft in order to run an airline? Clearly not, evidence suggests.

- Does one have to own all of the staff to make a consistent brand standard of service? This is increasingly not the case.

- Does one have to have a singular monolithic brand to be a successful airline? Clearly not; multi–branding can work even better.

- Do those who service those who fly the aircraft make more money than the aircraft owner/operators? Absolutely yes.

- Will the first significantly sized airline to evolve a recession–proofing programme that works over the life of a cycle win out? Absolutely yes.

- Has anyone developed such a programme? Clearly not.

- Is stand–alone organic growth the way to build a successful growth profile over time? Clearly not anymore; a mix of organic and aligned growth is the best way.

- Is there therefore an optimal structure and market approach that can encompass all of the airline management truths that seem to be self–evident to the trained observer? Unknown.

A virtual rebirth - BA?

When one considers these questions in depth then some interesting things emerge, particularly when a series of recent moves by British Airways is examined more closely. BA appears to be adopting a series of measures to clip costs while at the same time keeping service standards on the up and up. These moves include outsourcing, a regional franchisee network and the current fleet renewal (where manufacturers were asked to be creative financially). But does this mean that BA is making a serious attempt to become the world’s first virtual airline?

Let’s start with the new BA branding scheme. This has been greeted with scepticism, but those who feel that way are failing to see beyond the paint. BA’s brand evolution system provides two breakthroughs, the first of which is relatively infinite brand variation that can be linked to various geographic brand symbologies, as well as being flexible enough to encompass alliance with partner brands. BA has now gone beyond being solely British, which is made possible due to the positive global brand equity it has built up, as well the strength of sub–brands (Club, First, etc). The second breakthrough is that BA can continuously evolve this brand system without ever (in theory) having to come out with a totally brand new system.

The fact that BA no longer insists on "out side the- tube" brand homogeneity does not mean that it doesn’t insist on inside–the–skin product and sub–brand alignment. In fact, the core of any virtual firm is the brand line/service process combination.

Another clue to BA’s motives is given by its fleet renewal plan. The crux of the question is really whether BA needs to be directly involved in any kind of aircraft ownership proposition, or whether a rented, arms–length relationship is just as effective. In fact, the premise that the residual value of aircraft anchors the balance sheet may become outdated if residual brand value and equity (i.e. goodwill) become the preponderant assets in a virtual set–up. We also know that the operator/owner does not necessarily yield the best returns; in other words manufacturers will have to get their heads around risk sharing and asset ownership that goes beyond just a lease deal and service arrangement.

Add to these moves all of the franchising, outsourcing and proposed alliance plans that BA has, and one can start to build a case that BA is in a race to become a virtual airline.

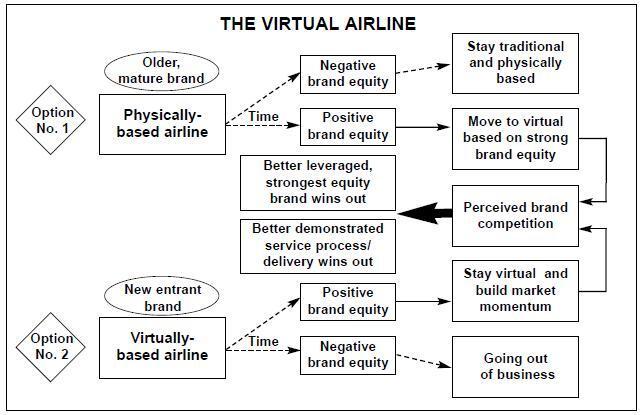

But could BA really be adopting a pioneer strategy that has gone mostly undetected by others? And, if so, two further questions arise — will BA succeed and what kind of competitive advantage could it gain? Only time and the impact of other virtual airlines (see diagram, below) will tell on the first question, but on the second, a perfectly executed virtualisation could recession–proof the costs of physical delivery of units of service.

It seems that strategists would be wise to analyse again the merits or otherwise of the virtual airline, because the concept just might be the forward leap that the airline industry is looking for.