Southwest: now appearing in the East

April 1998

After saturating many of its traditional markets in the western half of the US, Southwest has turned its full attention to the East coast. It is gearing up for major expansion at Baltimore and in New England, where it will clash head–on with US Airways' MetroJet this summer. Will the pioneer of low cost travel emerge as the winner as always before?

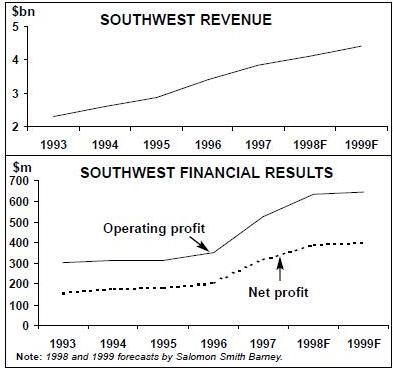

Despite its rapid growth and the tough challenges posed by the East coast environment, Southwest has continued to report record earnings and the best profit margins in the industry. It has now been profitable for 25 consecutive years.

It has achieved such consistency by avoiding the mistakes made by others — notably over–ambitious expansion. It took 12 years to grow its fleet to 50 aircraft and did not venture out of its traditional southwestern and West coast territory until the early 1990s. Chicago was added in 1991 and Baltimore in 1993. Florida followed in January 1996 — its strongest eastward push so far — and Providence (Rhode Island) in October 1996.

In contrast to the earlier years, Southwest has grown rapidly in the 1990s. Its strategy is to expand capacity by about 10% annually. However, it does not over–extend itself as, typically, most of the new capacity is used to boost frequencies and only one or two new destinations are added each year.

This and the strong profits have enabled Southwest to maintain a healthy balance sheet. At the end of 1997, it had $623.3m in cash, plus an available and unused bank credit facility of $475m, and very little debt. Until very recently, it was the only one of the major carriers with investment–grade credit ratings.

Southwest takes care not to provoke larger competitors. It uses secondary airports or older terminals that bigger carriers snub. The beauty of this strategy is that it gets the traffic because people are willing to drive 40–50 miles to get cheap fares, yet it does not directly confront the largest airlines at their hubs.

This has enabled Southwest to quietly grow into the nation’s fifth largest carrier in terms of domestic passengers, now serving 51 cities in 25 states with 2,300–plus daily flights.

The DoT’s new draft guidelines on competitive practices, leaked to the press in mid- March, note that while the high–cost carriers appear to be using unfair tactics to stifle or drive out weaker low–cost competitors, they prefer to co–exist with companies like Southwest that have enough wherewithal to battle for market share.

Southwest certainly showed its strength in the war that broke out in California after United launched its Shuttle in late 1994 — the first time that the low–cost carrier had ever been so directly and highly visibly challenged in one of its core markets.

After initially losing market share, Southwest emerged as the winner when the Shuttle, unable to reach its cost targets, retreated from many competitive markets and became essentially a feeder for United at the San Francisco and Los Angeles hubs.

However, occasional mistakes made by Southwest over the past three years, which caused its profits to dip in some quarters, have showed that it is not invincible.

First, it over–extended itself with growth in 1994 and had problems integrating Morris Air.

Second, it responded to the sudden surge in low–cost competition three years ago by launching extensive and highly damaging fare sales.

Third, in the summer of 1996 it inexplicably went into a market–share expansion mode, again sacrificing the yield through heavy discounting.

The market share expansion strategy was quickly abandoned in early 1997, when the impact on earnings became evident, and Southwest actually implemented some marginal fare increases. This led to substantial quarterly profit surges throughout last year and restored confidence in the predictability of the company’s future earnings.

In the second half of 1997 Southwest also benefited from the stabilisation of the West coast fare environment. Its fourth quarter net earnings nearly tripled as its average fare rose by 18.4% (to $74), yield improved by 14.5% and unit costs fell by 1.7%.

Unique low-cost formula

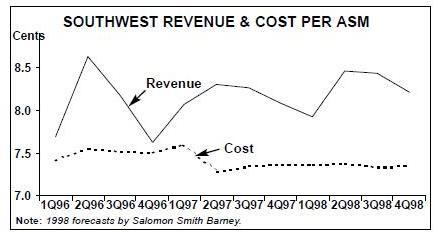

Southwest has the industry’s highest profit margins because its passenger yield, at 12.84 cents per RPM in 1997, is comparable to the yields of the larger carriers (except US Airways), yet its unit costs, at 7.40 cents per ASM, are 15–20% below those of American, United, Delta, Northwest, Continental and TWA.

Many start–up carriers have copied Southwest’s basic short–haul, point–to–point, high–frequency, low fare strategy, but have failed miserably. No–one has been able to emulate Southwest’s business model: low unit costs, a no–frills but otherwise exceptional service and a highly motivated work force.

Southwest’s product is basic: no first class, no meals, no assigned seats. The emphasis is on a friendly and professional service that caters for both leisure and business travellers.

The airline attracts substantial volumes of business travellers because of its focus on things that matter most to that segment: high frequencies and punctuality. For the past five years, it has come top of the DoT’s on–time performance, baggage handling and customer satisfaction rankings.

It has achieved that consistency by being extremely strict about everything that may affect efficiency and reliability. For example, it is spearheading the current industry–wide crackdown on multiple or excessively large carry–on luggage items.

There have never been any negative perceptions about Southwest’s safety because it is a large, well–established and conventional operator (doing its own maintenance, among other things), has never had an accident and operates one of the youngest fleets in the industry (average age just 8.3 years).

Southwest’s unit costs are so low because of the efficiencies offered by a uniform, modern 737 fleet, rapid 20–minute turnarounds and favourable labour contracts. It also saves money by operating from cheaper secondary airports and offering a no–frills product.

The carrier has benefited enormously from a 10–year contract signed with the pilots in November 1994. The deal froze salaries for the first five years and granted 3% annual rises in the subsequent three years, in return for stock options.

One of the things that really sets Southwest apart from its rivals is the way it treats its employees. The company goes to great lengths to attract the right–quality staff, train them well and then motivate them to outperform their counterparts at other carriers.

Public recognition of Southwest’s unique corporate culture came when Fortune magazine recently declared it to be "the best company to work for in America". In a previous 1993 survey, Southwest was voted the best for job security, opportunities (among the youngest companies) and "where fun is a way of life".

The corporate culture is maintained through a personality cult. Fortune said of chairman, president and CEO Herb Kelleher: "He spends his business life making sure his employees believe in him and in the operation he has muscled into the top tier of a savagely competitive industry."

Workers are also motivated through a profit–sharing programme, which has been in place since 1974 and has received a total of $353m in contributions. This year the company will pay out $91m (based on last year’s profits), which will represent about 11% of eligible salaries.

Blazing success in Florida

Southwest’s Florida operation was an immediate success, with high load factors and stronger than anticipated revenues, so frequencies were built up rapidly during 1996, the initial year of operation. By mid–January 1997, when also Jacksonville had been added to the network, Southwest’s operation included 90 daily flights from four Florida cities.

The carrier quickly became a dominant force in intra–Florida markets, which had previously been served mainly by commuter operators charging high fares. Its shuttle–type service offering advance purchase fares as low as $29-$32 has diverted huge volumes of traffic off the roads.

For example, passenger numbers on the 200–mile Ft. Lauderdale–Tampa sector were 2.5 times higher in 1996 than a year earlier, with Southwest capturing an 87% market share or 424,000 passengers.

The strategy of serving Florida with relatively low frequencies from numerous Midwest and East coast cities has also worked well. With advance purchase and walk–up fares as low as $89 and $159 respectively, Southwest has generated much new traffic. Passenger numbers from cities such as Baltimore, Providence and New Orleans typically doubled or even tripled in 1996.

The Florida operation, which was already profitable last year, has clearly been Southwest’s most successful regional growth effort so far. This month (April) will again see some frequency increases. However, future expansion potential may be limited because there are signs that the markets could become over–saturated. America West is now challenging Southwest on the Ft. Lauderdale- Columbus sector. Kiwi is back after its Chapter 11 reorganisation. Delta Express, which so far has competed head–on with Southwest in only a few markets, is again in an expansion mode.

But the most direct assault will come from US Airways, which will target its new low–cost subsidiary MetroJet specifically on the Northeast and Midwest to Florida markets. This summer it will enter the Baltimore–Ft. Lauderdale and Baltimore–Tampa routes, with 3–4 daily nonstop flights, connections from three other Southwest points (Cleveland, Providence and Manchester) and fares that slightly undercut those of Southwest.

Northeast expansion

Southwest’s current Northeast focus is a critical part of its long term strategy and reflects the success of the Baltimore and Providence experiments, but US Airways' moves have obviously added a new sense of urgency.

US Airways announced on February 4 that MetroJet will focus on Baltimore when it begins operations on June 1, linking that city with Cleveland, Providence, Ft. Lauderdale and Manchester (New Hampshire) with high–frequency, low–fare services utilising five 737- 200s. Tampa will follow on July 6 and more destinations will be announced on a monthly basis. The operation could utilise about 20 aircraft by the end of this year.

Over the past five years, Southwest has built up hub operations at Baltimore at a fairly leisurely pace. It has inflicted some damage on US Airways, which has lost traffic on routes such as Washington–Boston and Washington–Cleveland as travellers have been willing to drive to Baltimore to get low fares.

Baltimore expansion is logical also because the airport is not capacity–con- strained. But Southwest waited until hearing US Airways' plans for MetroJet before announcing major expansion there.

It now intends to add 10 gates at Baltimore by the year 2000, to increase its gates to 16. This will mean a trebling in capacity, from the current 50 to as many as 160 daily flights. It also plans to open a crew base there this year.

By comparison, MetroJet will initially utilise only three gates at Baltimore, though it has better immediate growth potential as US Airways currently has 22 gates at that airport.

Like the Florida markets, Providence has shown exceptional traffic growth since Southwest arrived 18 months ago. It has proved itself as an attractive alternative to Boston’s congested Logan International airport.

The Providence–Baltimore route, where Southwest introduced a virtual shuttle service with unrestricted one–way fares of $59 (compared with US Airways' $289 on Washington- Boston), grew to more than 500,000 passengers in 1997, up from just 57,100 in 1996. The carrier is now constructing additional gates for expansion.

In mid–March Southwest announced that it would add Manchester to its network on June 7, offering a high–frequency service to Baltimore, one or two daily flights to Chicago/Midway, Nashville and Orlando, and direct connecting service to 25 other cities.

Like Providence, Manchester was chosen because of its low air traffic congestion and its potential to draw traffic from Boston suburbs. But its location (45 miles north of Boston) also offers a new catchment area, enabling the carrier to further penetrate northern New England.

The stage is now set for a mighty clash between Southwest and MetroJet in numerous East coast markets this summer. The Baltimore–Manchester confrontation will be particularly interesting, because the two will enter that market within a week of one another. Southwest has set its fares one dollar higher than MetroJet’s but will have the edge with eight daily frequencies compared with MetroJet’s three.

US Airways' wisdom in taking on Southwest so aggressively is questionable, because it will not be able to get MetroJet’s costs anywhere near Southwest’s levels. Its strong East coast position will help MetroJet succeed in at least some markets, but it will not beat back Southwest.

Coast-to-coast operations

Over the years Southwest has been quietly introducing some long–haul services. This process has intensified as a result of the East coast expansion, the opportunity to develop Nashville (Tennessee) as a focus city and the availability of longer–range 737s.

Southwest began to expand rapidly at Nashville when American closed its hub there in 1995. In April 1997 it linked Nashville with Oakland and Los Angeles and began offering one- stop coast–to–coast services for the first time (to Florida, Baltimore and Providence). Nashville also acts as a connecting point for some flights from northern cities to Florida.

In April the carrier is introducing new longhaul services that bypass Nashville, linking Baltimore with Houston and New Orleans and Kansas City with Portland and Orlando. The latter will facilitate another direct one–stop coast–to–coast service, Portland–Orlando, with a 25–minute stop in Kansas City.

Southwest’s unrestricted fares on the long haul sectors are typically around half of what competitors charge, and as a result it gets the traffic. However, because the services involve a stop, the larger airlines generally do not bother to match the low fares. In 1997 connecting traffic accounted for just over 20% of Southwest’s total passengers.

The longer haul services are partly aimed at keeping unit costs low — Southwest estimated last year that the Nashville–California flights cost it only about four cents per ASM (excluding any meals). The new 737–700 offers further cost savings and will enable longer sectors to be flown.

However, at present Southwest regards long–haul services essentially as an experiment, giving it more flexibility to respond to an economic downturn or new opportunities. It will not fundamentally depart from its proven short haul strategy.

Fleet and growth plans

In November 1993 Southwest became the launch customer for the 737–700, which will become its main workhorse and cater for growth well into the next century. The 737- 700 fleet will also significantly help it retain its unit cost advantage over competitors.

Following the original order, in January 1998 Southwest came back to exercise options on 47, order an additional 12 and option another 42 aircraft, which brought the total 737 order to 191 aircraft (see table, page 9). Deliveries of the firm orders are currently scheduled to run through the year 2004.

The first of the 737–700s entered commercial service in mid–January and so far four have been delivered. Southwest’s current 262–strong fleet also includes 186 300–series, 47 200–series and 25 500–series 737s.

But the happy occasion of introducing the 737–700 has been overshadowed by the problems caused by delivery delays and continued uncertainty about whether Boeing will be able to meet the delivery schedule for the remainder of this year (21 more aircraft were due in 1998, including three in March).

Southwest received several million dollars from Boeing as compensation, but it had to delay some of its growth plans. The company recently estimated that its capacity would only increase by 6–7% in 1998 but then resume the customary 10% annual growth in 1999.

The situation has been somewhat alleviated by Southwest’s ability to purchase and lease four 737–300s formerly operated by Western Pacific, which will enable it to go ahead with the new services planned for April. In mid–March Southwest was sticking to its earlier plan to announce another focus city this year, with service possibly beginning in early 1999, but it is not clear whether the revised aircraft delivery schedule will allow that.

While Southwest will probably also want to wait and see how the competitive situation develops with MetroJet, there continues to be speculation that the next new focus city will be in the New York region.

The high costs and the air and ground congestion that characterise the area have put it off so far, but the more Southwest expands in the East, the bigger the New York gap will seem. It is known to be considering secondary airports such as Islip on Long Island and Hartford in Connecticut (both already served by Delta Express), as well as Allentown in Pennsylvania.

New cost challenges

Southwest’s success in New England has proved wrong earlier speculation that its costs would rise due to severe winter weather, congestion and other challenges posed by the Northeast environment. But the airline does face new cost pressures on other fronts.

First, as a domestic short haul carrier, Southwest will bear an increased burden under the new tax legislation, which will reduce the old 10% ticket tax to 7.5% and increase the new $1 per–passenger flight segment fee to $3 by 2002. The latter is estimated to cost short haul low–cost carriers in the US an additional $500m over five years.

Second, while going long haul may help the tax problem and reduce aircraft operating costs, Southwest’s traditional cost advantages (derived from lower labour and ground service costs) will be smaller on longer flight sectors, while catering costs would rise.

Third, now that airline workers everywhere are demanding hefty pay rises, Southwest can no longer take good labour deals for granted. Its flight attendants, after rejecting the company’s initial offer, secured a new six–year contract in December that grants them 4%-10% pay rises depending on seniority.

| Current Fleet | Orders(options) | Delivery schedule/comments | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 737-200 | 47 | 0 | |

| 737-300 | 186 | 0 | |

| 737-500 | 25 | 0 | |

| 737-700 | 4 | 125 (62) | 21 this year |

| Total | 262 | 125 (62) |