EU duty-free abolition: an opportunity, not a threat

April 1998

Seven years after the EU announced that tax- and duty–free sales would be abolished, Europe’s vocal duty–free lobby is still trying to overturn the decision. Their reasoning is simple — ever since abolition was delayed from 1992 to July 1st 1999, the European aviation industry has been harvesting a last–gasp bonanza. EU duty–free sales have leapt from $3.9bn in 1991 to $6.1bn in 1996, and the duty–free lobby does not want the gravy train to stop.

Yet the powerful duty–free lobby has often overstated its case, no more so than by claiming that 150,000 jobs will be lost as a result of the change — a figure that is clearly over–inflated. But the duty–free lobby continues to press its case, and has been given a glint of false hope by the vote by EU transport ministers in March 1998 to review the effects of abolition.

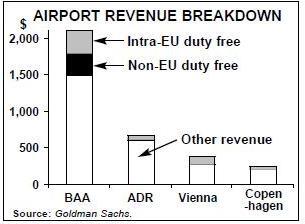

The problem is that there is absolutely no chance that duty–free abolition will be cancelled or postponed. All 15 EU finance ministers would have to agree, and the Danish and Dutch governments are determined that abolition will occur as planned. The only people who do not seem to realise this are those in the duty–free lobby. On the stock–markets the prices of quoted airport stocks — BAA, Vienna Airport, Copenhagen Airports and Aeroporti di Roma (which has just beaten BAA to the contract to run nine airports in South Africa) — have already been discounted discounted by the markets to take account for the July 1999 change, according to Guy Kekwick, London–based analyst for Goldman Sachs.

The debate is over

In any case, once the emotion is taken out of the issue the arguments in favour of abolishing EU duty–free sales are unanswerable. Duty–free sales are an unjustifiable anomaly, inconsistent with development of a European single market. They are an indefensible subsidy to airlines and airports, discriminating against those who either do not travel or go by train and car. And thousands of newsagents, off–licenses and tobacconists in the UK, for example, would dearly love to see the end of this subsidy too, but the UK duty–free lobby conveniently forgets this. And, finally, the EU is not alone in its actions — the move is likely to be copied by NAFTA and Mercosur

Yet debate about the merits or otherwise of duty–free abolition is completely irrelevant, since abolition will take place regardless. What is much more important is how abolition will affect airlines and airports and, unless they are completely relying on the duty–free lobby to win through at the last minute, what plans they have developed over the last six years to replace the lost income.

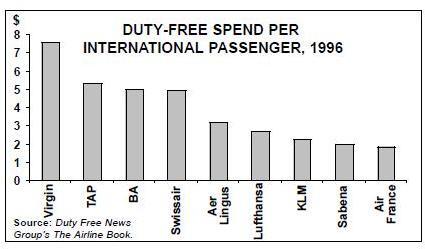

Clearly airports will be hardest hit. In 1996 duty–free spend per passenger was $4.82 on EU airlines, $17.26 in EU airports, and (as a comparison) $25.25 on EU ferries. But these average figures hide a large variation between individual airlines and airports (see charts, left and above right).

The most basic way airports can replace EU duty–free income is to raise take–off and landing fees — or at least that is what the duty–free lobby is threatening. The UKbased Duty–Free Confederation claims that as a result a typical family will pay an extra $92 per package holiday to a European destination. This is scaremongering, but regulators have allowed Copenhagen Airports to increase landing fees by up to 15% in both 1999 and 2000, and BAA also has permission to raise fees.

Some airports claim they will have to raise fees because otherwise they would not be able to finance much–needed improvements to airport infrastructure. That argument is simply not valid. Why should airlines be billed in advance for airport investment? If airports do not have a viable enough business case to raise the money on the financial markets, then airlines should not suffer as a result.

How much landing and take–off fees will be raised at individual airports next year will depend on how much compensatory income comes from the retail side. As Guy Kekwick points out, BAA — and to a lesser extent Copenhagen Airports — has “shifted the focus of their business away from the regulated landing, passenger and handling fees to the more interesting and dynamic retail side of the business”.

It is ironic that the more commercial airports will have most to lose, since they have a greater amount of duty–free sales, but on the other hand these airports are the best placed to replace lost revenue with duty–paid sales. This is a point of debate the duty–free lobby is quick to downplay, but the fact remains that the potential for duty–paid sales at the more commercial airports is huge.

Tax–paid airport shopping has been very successful in the US, and as well as the traditional captive market of air travellers there is no reason why European airports cannot develop retail well enough to attract non–flying shoppers within a local catchment area.

A change in mindset

To do this, however, airports have to change their mindset — from being national or local government–owned utilities to being commercial, transnational companies. That may mean bringing in expert retail advice from outside — a considerable strategic shift for the majority of European airports that are still controlled by national/local government. As for airlines, with far lower exposure to duty–free sales, they have less to lose — unless airports increase landing fees disproportionately. KLM UK (formerly Air UK) has already dropped on–board duty–free sales (from April 1st), but it claimed that the 1999 abolition was a minor factor in its decision — the deciding factor was that passengers preferred the better range of duty–free goods available at Schiphol.

However, unlike airports, airlines have much less scope to increase duty–paid sales. Today much of the non–alcohol/tobacco sales on airlines are, quite frankly, cheap and tacky. Airlines therefore have two choices: if duty–free only contributes a very small amount of revenue it can be stopped altogether (as with KLM UK); or else airlines will have to come up with new ranges of goods that passengers will actually want to buy in–flight rather than at airports.

Here again, outside retail expertise may have to be brought in but, as with airports, a little bit of creativity may prove to be very profitable. For example, there is potential for airlines to link in–flight sales to FFPs via mail–orders catalogues, perhaps via a link with a major high street brand. Airlines must consider duty–paid sales not as marginal revenue, but rather as a whole new market to be explored.

In fact, creativity and imagination is the key to airlines and airports replacing the revenue they will lose from duty–free sales. And that is more likely to come from those in the aviation industry that see the abolition of duty–free sales as an opportunity, rather than an absolute loss.