EADS: showing initial promise

May 2001

While Boeing grabs the headlines around the world with the sonic cruiser, Airbus is consigned to a period of calm after last year’s excitement over the launch of the A380. It is as if Boeing had taken a leaf out of the aggressive marketing and publicity campaign behind the Airbus super–jumbo (all that stuff about gyms, jacuzzis and casinos), and decided to flam up its potential new offering to drum up interest among airlines. As for EADS, Rainer Hertrich, co chief executive, remarks that Airbus itself has such designs in its concept list, and awaits with interest market reaction to the Boeing proposal before EADS decides what should be its response.

So now is a good time to look at the financial performance of the two companies engaged in such titanic struggles. Boeing has managed a thoroughly creditable improvement in profits — its net profit in 2000 was $2.2bn, an increase of 14%, on revenues of $58bn, demonstrating a healthy recovery from the dire straits that a misguided price war against Airbus on narrowbodies placed it in (see Aviation Strategy, February 2001). While Boeing’s profitability dwarfs that of EADS, there is some positive news emerging from Airbus’s parent (EADS owns 80% against BAE System’s 20%).

At headline view, EADS is a company with sales of more than €24bn, of which 75% is in civil activities. EADS is the third largest aerospace company in the world behind Boeing and Lockheed Martin. It employs 87,00 people at more than 70 sites in France, Germany, UK and Spain. Legally the company is registered in Amsterdam, but in reality its head office is split between Paris and Munich. The HQ staff of some 1,100 is about to be halved as part of the ongoing rationalisation of what was always bound to be a complicated company formed from the merger of France’s Mart Largardere Aerospatiale with Dasa, the aeronautics arm of DaimlerChrysler.

Unsurprisingly, EADS is a rather cumbersome- looking company with an extremely complex portfolio of businesses. For a start, the company has two chief executives. Then, some two–thirds of its business is actually in one or other form of joint ventures, usually with BAE, but also involving others such as Alenia, the aerospace subsidiary of Finmeccanica, an Italian state–owned company in the midst of privatisation.

It had looked like a recipe for confusion, obfuscation and bad financial news. Indeed when the two chief executives Philippe Camus and Rainer Hertrich were doing their roadshows around the flotation of about one third of the shares last summer they were both very defensive about the double–headed control of the company. Now both are much more relaxed: they have found a way of making a system which both acknowledge as less than perfect work.

There are also clear indications that they are implementing an effective plan to change the sourcing strategy of the company from a bureaucratic to a commercial basis. More than half the €60m synergies EADS intends to achieve in 2001 will come from a harmonised purchasing policy. This will apparently not just involve more competitive bidding but also risk and revenue–sharing partnerships.

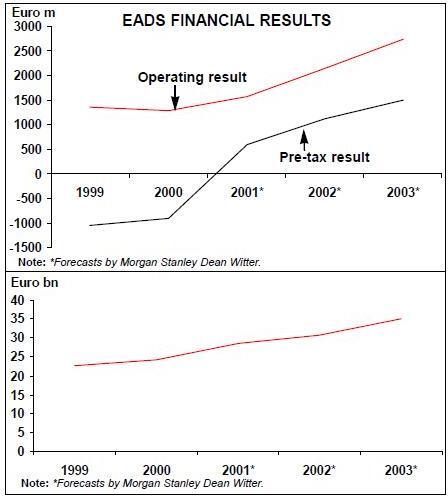

EADS’s 2000 results were, as mentioned above, better than expected (although the financial figures are unusually complicated by one–off items and an adjustment to a more realistic and benign euro/dollar exchange rate than the rate outlined at the company’s flotation last year).

Earnings before interest and tax adjusted for disposals show an 11% rise to €1.4bn. Even more revealing of a relatively healthy business is the rise in free cash flow from barely €200m in 1999 to €1.5bn in 2000. Both order intake and backlog have shown healthy rises of 50% and 29% respectively. Management is forecasting rises of earnings before interest and tax of 15% over the next few years, and has raised its target for operating margin by the year 2004 from 8% to 10%.

EADS ownership structure

EADS’s ownership structure is inevitably complicated. Private investors hold is 30.81%. Then DaimlerChrysler and an entity known as SOGEADE (amounting to the French state and the French Lagardere group) each own a further 30.29% each. The Spanish state–holding company Sepi owns 5.53%. DaimlerChrysler and the French state owns some residual "excess shares" of around 3% destined to be floated as part of a general tidying up.

By far the biggest part of EADS is Airbus, accounting for almost 68% of turnover and all of its profits because of various write–offs on the other businesses, namely, military transport, aeronautics, space, and defence systems. The Airbus contribution will be flattered in this year’s financial figures when the company will be entitled to consolidate 100% of the sales and profits of its 80% subsidiary. Conversion of Airbus from a French consortium known as a Groupement d'Interet Economique (GIE) into a fully–fledged company, known as Airbus Integrated Company (AIC), was decided upon last June, but the technicalities have dragged on. Five months overdue, they are supposed to be completed in May, according to Rainer Hertrich.

Central to any view of EADS is the outlook for Airbus, and more specifically the prospects for the A380. Some 47% of the development cost of $10.7bn falls to EADS and is being expensed through operating cash–flow. The rest is covered by risk–sharing industrial partners and by participating European governments offering soft–ish loans re–payable from revenues.This cost had been expected to depress operating margins from 10% to 8%, but because some conservative estimates on other counts have been adjusted, this is no longer the case.

Hertrich confidently expects today’s 62 firm A380 orders and 40–odd options to convert into the 100 firm orders which John Leahy, Airbus vice president for customer relations, expects. Thereafter, with the end of the launch period and the special discounts that go with it, he expects a complete lull in orders until the new aircraft is coming close to entering service in late 2006. This would be in line with the ordering pattern for other radically new aircraft. Only when Cathay Pacific and SIA are operating the A380 will carriers like JAL (a long–time Boeing devotee, with the largest fleet of 747s) be willing to commit to this aircraft.

Moreover, the question of European government support for the A380 is not going to go away. The EC has sent details of the financing plan to the US government, which has been demanding proof the loans conform with a 1992 agreement, which allows government loans on a commercial basis for a maximum of 33% of the development costs of new aircraft. Germany has pledged about €900m, France about €1bn and the UK €750m to in development loans to the project. Spain, Belgium, the Netherlands and Finland also have promised smaller amounts because they have domestic companies involved in the project. Italy and Sweden may also contribute.

Even if the US authorities agree that the investment loans meet the criteria of the 1992 agreement they could also challenge the Europeans under WTO rules.

Analysts, such Tim Bennett at Morgan Stanley Dean Witter, estimate that total Airbus deliveries (which produce sales cash some two to three years after orders are booked) will be 350 in 2001, rising to around 450 by 2004. This compares with deliveries of 311 in 200. The one big worry on the Airbus side is that the cyclical decline in profits at US airlines will lead to cancellations of orders by airlines such as United and US Airways, with 150 order for single–aisle aircraft between them. Airbus also has a heavy exposure to the leasing companies, which account for about 30% of the company’s order book.

Leaving such worries aside, there is the fact that Airbus has confidently achieved the market share target framed by its former management Jean Pierson and acquired a 50% share of order intake in the market for civil jets of more than 100 seats. That is more than a matter for satisfaction in the Airbus camp, but an interesting indicator of its ability to carry on at this level or better. It should be remembered that the Airbus increase was obtained at a time when two thirds of the airborne fleet was Boeing, with a built–in bias towards continuing that split because of maintenance and training issues. It seems, however, that keen Airbus pricing and the inter–operability across the company’s company’s family of aircraft, ate away at this inbuilt Boeing advantage. The other big factor was that the A320 family has turned out to be a more attractive product than the 737NG, which was stuck with a narrower fuselage.

The rest of EADS

To get a quick impression of how important the rest of the company is: EADS is number one in the market for commercial space launchers; number two in helicopters; number two in missiles; number three in satellites; number three in military transports and number four in military aircraft through its 43% stake in Eurofighter and its 46.5% stake in Dassault, the partially–private French maker of fighters.

It has three strategic objectives: to be number two in aerospace and defence and number one or two in other business areas, while expanding business activities in all regional markets. Its ambitions in the aerospace field are helped by the fact that it now wins about 50% of orders in competition with Boeing for jets over and above 100 seats. In defence aerospace, its recent addition of Italy’s Alenia to its Matra Marconi joint ventures means that it is well–placed to challenge Raytheon and other American leaders in the defence missiles field.

The company is now organised into five divisions. One is Airbus, run by Noel Forgeard, an old Largardere figure, like Philippe Camus. The others consists of: military transport aircraft (essentially the project to build the A400m military transport); aeronautics (which means helicopters, regional aircraft, Eurofighter and other bits); space (which is launch vehicles, Astrium and other bits and pieces); defence and civil systems, which includes EADS missiles (just about to be put into MBDA) and defence electronics.

As if this divisional structure were not confusing enough, much of the business involved is actually part of joint ventures, notably with BAE. As part of the great bargaining round which accompanied the conversion of Airbus into a proper company, BAE had sought to establish equity stakes in several of the defence and space businesses, but gave up when it was clear that it would not get its way. The formation of Airbus as a proper company was the principal aim. At the last count, according to Hertrich, some 70% of EADS is bound into joint ventures.

Key prospects

Assuming that the A380 gets close to its sales targets and does not run into an aggressive trade war from George W. Bush determined to preserve Boeing’s hegemony, Airbus is well placed in the long term.

In the short term the cumbersome structure of EADS may not prove to such an obstacle as it first appeared. Dual–nationality at chairman and chief executive level has some important advantages — it needs a Frenchman to sell projects to the French government, and vice versa. Moreover, both Camus and Hertrich are essentially highly numerate finance people rather than romantic engineers.

EADS does have to find a way to develop more sales in America, beyond the inroads it has already made with the A320 family. It has already reached an important agreement with Northrup Grumman in defence electronics and won some other contracts for the US Navy with that company.

Perhaps the ultimate test for EADS will come when BAE, its partner in so many European defence activities (as well as in Airbus), eventually decides, as most analysts believe it will, to align itself more closely with Boeing. As part of its attempt to launch as the 747X, Boeing approached BAE to get it to build the wings. BAE was quite happy to find a way of accommodating both its Airbus partners and the Americans, but the project never got off the ground. Nevertheless, such dalliance shows one problem EADS has in keeping the European aerospace show on the road.

| 2000 | 1999 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| pro-forma | pro-forma | Change | |

| Revenues | 24,208 | 22,553 | 7% |

| EBIT* | 1,399 | 1,445 | -3% |

| EBIT* adjusted for | |||

| Sextant disposal | 1,399 | 1,263 | 11% |

| Free cash flow | 1,531 | 198 | 673% |

| Net income | -909 | -1,046 | 13% |

| Order intake | 49,079 | 32,700 | 50% |

| Order backlog | 131,874 | 102,400 | 29% |

| Employees (Year-end) | 88,879 | 88,631 | 0% |

| Revenues | EBIT** | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 1999 | 2000 | 1999 | ||

| pro-forma | pro-forma | pro-forma | pro-forma | ||

| Airbus** | 14,856 | 12,639 | 1,412 | 925 | |

| Military Transport Aircraft | 316 | 241 | -63 | -20 | |

| Aeronautics | 4,704 | 4,280 | 296 | 202 | |

| Space | 2,535 | 2,518 | 67 | 97 | |

| Defence & Civil Systems | 2,909 | 3,830 | -110 | 86 | |

| Eliminations/headquarters* | -1,112 | -955 | -203 | 155 | |

| Total EADS Group | 24,208 | 22,553 | 1,399 | 1,445 | |

EADS ORDERS BY DIVISION (EURO M)

| Order intake | Order backlog | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 1999 | 2000 | 1999 | ||

| pro | pro | pro | pro | ||

| forma | forma | forma | forma | ||

| Airbus** | 34,158 | 20,700 | 104,387 | 79,500 | |

| Military Transport Aircraft | 493 | 600 | 873 | 700 | |

| Aeronautics | 8,322 | 4,900 | 13,067 | 8,800 | |

| Space | 3,024 | 2,200 | 4,826 | 4,400 | |

| Defence & Civil Systems | 3,857 | 4,300 | 9,722 | 9,000 | |

| Eliminations & headquarters* | -775 | 0 | -1,001 | 0 | |

| Total EADS Group | 49,079 | 32,700 | 131,874 | 102,400 | |